|

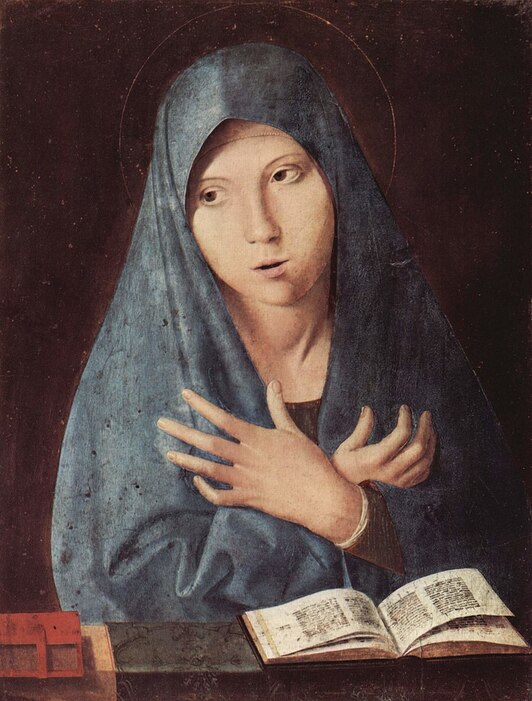

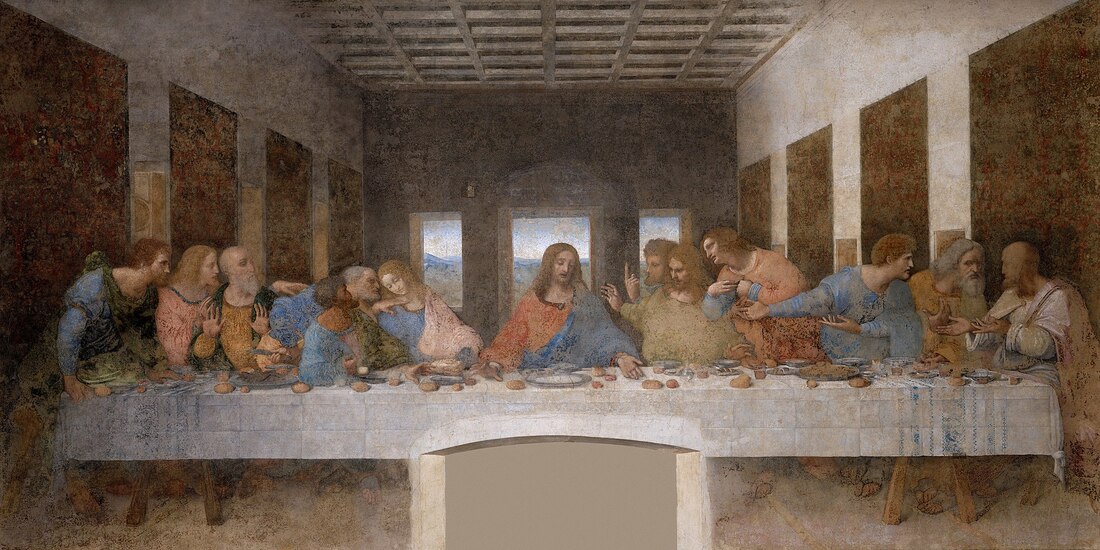

This is the second in a series of three texts that are exciting and meaningful to me. Don't you enjoy how standing in front of someone's bookcase tells you things no other method of learning about them could? This series is a bit of my mental bookcase. My first essay was on Steinbeck's East of Eden. My second, below, is on a painting not many know about. 2. Annunciate Madonna, by Antonello da Messina, 1476. Oil on wood; 17.5 in x 13.6 in. Currently in Palermo, Sicily. Click here for an up-close, full-size version of the painting, courtesy of Wikipedia. People don’t talk about Antonello da Messina when they talk about Early Renaissance Italian art. They talk about Botticelli. They talk about Piero Della Francesca. Maybe they talk about Fra Filippo Lippi. But who was Antonello? Where’s Messina? How many artists have worked alone with passion and skill, in unknown rooms? Something compels me about these hidden lives, the daily truths lived, textures of ordinary existence and struggle untainted by the anomalies of wealth and attention. In school I gravitated toward the classmate who sat in the corner of the room or alone at their lunch table, just as I now find myself drawn toward these souls. Perhaps because I am one of them. The onward flow of the human project is embodied most fully not by rulers and despots but by people on the ground, those with dirt in their fingernails and whose souls are just as deep with experience filled to bursting, but who from the outside we forget to take notice. The divide would have felt wider for Antonello, as the royal court spoke different languages (Catalan, Aragonese) than the citizenry (Sicilian) at the time. The plates and jars and clothes of these peasants, masons, carriers, maids, smiths, cooks… do not survive in museums. Their dreams and ideas are recorded only broadly. These are the people I write about today. 1. The Times Born in Messina in 1430, where he would later return to die only 49 years later, Antonello lived under the receding shadow of the Black Death, by his lifetime part of the past but no doubt a recurring event in the perspectives and guiding principles of his elders. He would have heard stories growing up. Messina was a port city on the island of Sicily, and in 1347 “death ships” were sent to Messina from the Genoese city of Kaffa (now the disputed Feodosia Municipality in Crimea) and other eastern cities along the Asian trade routes. These ships were filled to the brim with dead and dying plague victims, who were then dumped on the island. Naturally this resulted in widespread death of Sicilian residents and the rapacious spread of the Plague into mainland Italy and Europe at large. Antonello wouldn’t be born for another hundred years, but what impact did being raised in the aftershock of this landscape have? How would it have affected the prevailing belief systems of the day? Writes historian Jennifer Hecht in her excellent Doubt: A History, “we simply do not know how much Christianity ever penetrated the great mass of peasants and workers of Medieval Europe…. Rural priests complained that their flocks showed up at church to gossip and play, and that when they took part they barely knew what they were saying.” Remember, the printing press and thus the Bible wouldn’t proliferate until well after 1453, and although Christianity was the sociocultural reference point for all classes in 1400s Italy, a new religious cynicism was spreading, partly as a result of the Church's wars on heresy and imposed economic turmoil. Historian Giulio Ferroni writes that this “lent greater importance among the middle classes to the tangible and utilitarian aspects of life.” Then as now, times were complicated, and as ever there is so much we don't know. Not much is written about Messina in the 1400s, other than a university being built in nearby Catania, a slightly larger city and over a day’s journey on foot. Did Antonello think about this? Did he ever go there? We don’t know. 2. The Craft We believe he apprenticed in Rome and then moved to Napoli, where Netherlandish painting was in vogue. He loved Van Eyck. He loved the Flemish tendency toward infinitesimal detail and careful attention to minute gradations of light. We think he was in contact with Van Eyck’s follower Petrus Christus in 1456, and suspect that Antonello taught Petrus Italian linear perspective; Christus is the first Netherlandish artist to employ the approach. Correspondingly, Antonello likely learned something of the northern tradition from Petrus, as Antonello is the first major artist in Italy to replicate Van Eyck’s oil-based, detail-oriented style. He must have gulped down these Netherlandish tendencies, because his work positively blooms with the approach: hyper-detailed minutiae, attention to light (down to the consideration of how light would land on light-absorbent objects like dark fabric), black backgrounds, frontal portraits (a novelty depending on where you were in Europe), and a tendency toward calmness and the enigmatic in facial expression and tone. Remember, this is before da Vinci. Writes Ingrid Rowland, “No one, not even Leonardo or Piero della Francesca, has ever paid such penetrating attention to the way light works. He knew nothing of photons or electromagnetic waves, but he understood, and recorded with uncanny penetration, the differences among beams, rays, reflections, glow, luminosity, and radiance. At the same time, he was a master of psychological detail and of nature, taking care to paint the reflections of infinitesimal ducks on a distant pond.” Why is the best-known portrait of Antonello vandalized? Why do portraits show him smirking, raising an eyebrow, or displaying other intriguingly quizzical touches? When a man leaves behind more questions than answers, we lean in. Giorgio Vasari, the preeminent Italian art historian responsible for as much fiction as fact, never travelled further south than Napoli, which is one reason why Antonello isn’t well-known. His accounts of Antonello are brief and disputed, written nearly a century later at a time when Tiziano’s entirely different style was the reigning subject of conversation. Vasari claims Antonello apprenticed with Van Eyck, which certainly never happened since Antonello was 11 when Van Eyck died; on the basis of nothing he also claims Antonello decided to live in Venice forever because of “pleasures and everything else to do with sex,” sounding suspiciously like a 16th-century version of The National Enquirer. The once-presupposed theory that Antonello majestically toured Northern Europe and its most famous painters’ workshops is now replaced by the more plausible understanding that the poor man came across a couple Van Eyck paintings on display in a 1445 visit to Napoli, and was thus inspired. What can be said is Antonello played at least some role in introducing oil paint to Venetian painting, as art in Venice (Bellini et al) looks different before versus after his visit there. 3. The Ephemeral The other reason Antonello isn’t well-known has nothing to do with skill, and everything to do with circumstance: Messina wasn’t only ravaged by the Plague. In 1783 and again in 1908, the city (located on a fault line, evidently not a concern when the Greeks founded it in 730 BCE) suffered two diabolically cataclysmic earthquakes, especially the 1908 iteration. That event leveled nine-tenths of the city’s buildings in under thirty seconds, with a subsequent tsunami and three hundred aftershocks decimating the rest. Only one of Antonello’s Messina altarpieces survives, and with heavy flood-induced water damage at that; most of the thirty remaining paintings we know of come from the brief year he spent in Venice in 1475-6, just a few years before his death. Scholars assume about ninety percent of his work is lost. What did he think about? What compelled him to paint snails and cats and potted plants in the backgrounds of his pieces? To paint Jesus “as a blunt-faced, almost homely man,” to use Ingrid Rowland’s words, “his reddened eyes brimming with tears and his mouth downturned in desolate sadness”? You look at a painting from 600 years ago and you recognize yourself, not in the face but the attitude of the brush: the same secret longings, the same confused awe at an inexplicable universe... look at us, trying to understand. Maybe no time has passed at all. Some say he had a son; another record shows he gave away a daughter to marriage. Maybe both are true. Two Sicilian scholars (Gioacchino Di Marzo and Gaetano La Corte Callier) assembled a life history of Antonello just before the 1908 earthquake, in which those painstaking compilations were promptly destroyed. We do know he was offered the role of court painter in Milan, but declined on the basis of Lord Galeazzo Maria’s tyrannical tendencies. Smart man, I say. Fame and fortune aren’t everything. 4. The Long Gaze Most artists don’t live to see their work admired; Antonello did not live, thankfully, to see the vast majority of his work destroyed. But the difference between one surviving piece and none is much greater than the difference between a few works surviving and many, and we at least have these thirty paintings. I believe he would be appreciated now if even only one of his pieces survived: his Annunciate Madonna (above), from 1476. Aside from oddly persistent simplification that Antonello “brought oil painting to Italy,” you could argue his reputation today stems primarily from this single image. What sets it apart from other paintings and artists of the time? Writes Rowland: “Of all Antonello’s paintings, the most remarkable, perhaps, is his Annunciate Madonna, a young woman who pulls a glorious true blue mantle close around her as she takes in the message the angel Gabriel has just delivered: she is to bear the son of God. Her right hand stretches out as if to pause the angel’s headlong announcement—or time itself—a brilliant exercise in foreshortening and a still more brilliant exercise in light, shade, luminosity, and the minute highlights that led curator Giovanni Carlo Federico Villa to call this ‘the greatest hand in Renaissance art.’ Many of Antonello’s Madonnas are plain-featured, with relatively short, small noses, in dramatic contrast to their aquiline-featured Byzantine counterparts or the long, haughty pointed profiles of the Dalmatian sculptor Francesco Laurana. But as two women passed by her image in Palermo recently, I heard one say to the other, “Now that’s a real Sicilian face. She’s siciliana, siciliana. I have a niece who looks just like her.” …[T]his Madonna, and her counterparts, for their very ordinariness, manage to create something more marvelous than transcendent beauty: the miraculous illusion of reality.” Compare that to this Madonna of the same event, painted by the same artist three years earlier. Much is the same– a young woman wearing a blue robe is interrupted in her reading. There is the black background, in true Netherlandish fashion. Yes. There are artfully painted hands. But this isn’t even the same ball game. In this 1473 version, Mary has already heard the ‘big news,’ or is perhaps in the process of hearing it just now. Its import, in either case, has already landed by the time of the moment depicted. She’s taking in the size of what she’s heard with reverence, and her reaction isn’t surprising: it’s a momentous moment, and she reacts accordingly. This is in keeping with earlier medieval art which, beautiful as it is, tends toward the decorative or instructional, with human faces often repetitive and mostly blank ciphers. These were images less of people than of ideas. The Renaissance involved integrating Classical Greek ideas from sculpture (not from paintings, which were all lost) into contemporary religious art. At the time this combination would have been an anachronism, but it achieves wonders in elevating the work. Compare Cavallini’s 1293 Last Supper with Leonardo’s famous 1498 version of the same scene: Human psychology is the main event of Leonardo’s piece; each disciple reacts to Jesus’ announcement of betrayal differently. There’s a lot to take in. No such nuance is visible in Cavallini’s piece (for a middle ground, check out Ugolino da Siena’s 1325 effort): If Antonello’s 1473 Madonna seems more tied to past periods, to earlier Medieval ideas of depiction– albeit with his trademark detail and care– the 1476 version is more of a piece with painting’s future: the Renaissance and all it would bring. I find it richer and more redolent of the multitudinous variations of human existence. Look at the full-blooded withholding of her face. Its ambiguity, discipline, quietude… holds us like a magnet. Antonello chooses an ethereal slice of being just after the big moment– or is it before? Perhaps Gabriel hasn’t even spoken yet. Mary holds out that now-famous hand in a gesture of staying, holding off what she doesn’t yet know is big news. She was reading. Not yet, she seems to say. Equally legitimate is the interpretation that she’s taking in what’s just been said to her. The news is too large for her to have an assembled response. Is she rejecting the idea? As in, No, that can’t possibly be me? Or is she accepting with grace and benevolence, rising into a new form of being? Either way she seems at once earthly in her tactility, and divine in her demeanor. On another plane, even while of this world. What other masterworks did Antonello paint, I wonder, which are forever lost to us? Were there works which surpassed even this one? Do lost legacies leave behind a phantom sensation of presence, in the way amputees can still feel pain in their absent limbs? I look upon this painting and experience something different than when I appreciate work by the better-known masters. This one is loaded. I look upon her face, the robe, the austere black and the impossibly truthful light and hand, and I see the 1908 earthquake. I see buildings levelled in seconds. Survivors picking through rubble. I see the biography those two historians gathered and composed, buried under stone. Loss, ephemerality, death: these are the galvanizing elements which teach us most about valuing things. Her face contains for me the heft of unknown secrets, mysteries known only to time, the oldest of surviving trees and rocks in the Messinan countryside. The Greek ruins at Paestum as I found them in 2015, five hours north of Messina by car. Built 900 years before Antonello's time.

Sources: Cardona, Caterina, et al. Antonello Da Messina: Inside Painting. Milano, Skira Editore, 2019. Cohn, Samuel K Jr. “Epidemiology of the Black Death and successive waves of plague.” Medical history. Supplement ,27 (2008): 74-100. Ferroni, Giulio. Storia della letteratura italiana vol. I "Dalle origini al Quattrocento." Turin: Einaudi, 1991. Hecht, Jennifer Michael. Doubt : A History. New York, Harpercollins, 2004. Rowland, Ingrid D. “‘A Painter Not Human.’” www.nybooks.com, www.nybooks.com/articles/2019/05/09/antonello-messina-painter-not-human/?lp_txn_id=1286657. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed