|

This post is a thematic sister to this post.

--- I will look back on these days with wonder. I will remember the texture of the everyday, the pleasing baseline of where we came from, what made a thing stand out. What is called ordinary now, which our future selves will wish we more deeply immortalized? I will remember the Camera Crew, two enthusiastic youngsters who remind me of myself in earlier times; I have a passion for people and cinema. They have a passion for taking pictures of unusual coach assignments. KING 5 did a piece on them and couldn’t get to the bottom of why they love taking bus photos so much. How could they? Passions need no explanation. Some may laugh at them, but I admire that they know what they like, what feeds their existence, and they simply do it. I will remember seeing them here, there, all around, cameras in hand waiting for the elusive shot, equal parts CIA surveillance and bird watcher. I will remember running for buses, and missing them. Making them. The involuntary smile of a person who just barely makes a bus. Isn't it lovely, how they always smile? The way the working man runs across the rainy sidewalk, artfully, holding a newspaper or book over their head from the drops above. Seeing a street fellow do the same, but with a seat cushion instead of the Times. I will remember the things we complained about. Have you noticed how some people express their joy through complaint? Schedules, runcards, route planning. Why the express lanes are closed today but not yesterday. Grumbling sarcasm unable to stay down for too long, manifesting as exaggerated jokes, chuckles over the things we tolerate. Looking at the ceiling of the Deca Hotel. Looking forward in the old Bus Tunnel, using your periphery to mind the narrow gap on either side while driving your 41 through the tubes. Do you remember the platform curbs before the rail retrofit, simple and easy to pull up to as any sidewalk? A 62 driver who’d driven me on an 8 the day before, she and I chuckling, me embarrassed I’d forgotten her name. I watch her walk down Mercer toward a comfort station from my day off, sitting in a cafe. I wonder how her day’s going, what thoughts live in her mind. How many times has someone we know seen us from afar, wishing they could say hello? The Chinese man playing the erhu in Westlake Station’s mezzanine, echoing the timeless sounds off the marble walls. I’ve seen him since childhood. Some say he has a twin brother who plays in the International District; others insist it’s the same man just making the rounds. Wonder if I’ll ever know. Young Gordon waving as I drive by his place, him and Bruce getting out of their car. A wave at night; you know who it is based on the block and time. I smile to myself in the dark. Geo, a friendly passenger, reading my book in the back of my own bus. To see that volume in her hands as she sits on the back bench, which I put so much into, my baby– as I do the very thing she’s reading about! Uncanny. Late one quiet night at the base, standing around under high ceilings. Satinder (called Bob) looks up at a few of us driver friends while filling out paperwork. He said, "I can't explain it, but I just had the strangest realization. For some reason I feel very confident that right now, today, is the halfway point of my life. I'm forty-seven years old, and I'm going to live another forty-seven years." There was a silent mystery in his tone, hovering behind the words. We believed him. On the 7 again after a stint away, making the route’s first turn after the Rainier Beach layover. A gaggle of youngsters on the sidewalk turn as I pass by, concentrating on driving. I don’t notice, but Brittany, standing next to me, does: “They recognized you!” “Really?” “Yeah, I heard them say, ‘Hey, Nathan's back!’” I have a feeling these are the sorts of flashes I’ll return to as I lay in bed, older, considering the ceiling markings and dim blue light from the windows. Life will shift in tempo, and a greater handful of thoughts will require too much energy to say aloud. I will slip away from myself, redolent with the weight of a past larger than my future, able to remember events but not their order. The last thing I will be able to do is think, and I know that in between thoughts of loved ones and the events which involved them, in between emptiness and loneliness and present solace, I will think of the masses who kept me company through these cluttered halcyon years. I spend more time with them per waking hour than anyone else, and I don't feel bad about that. There was something we shared, that spark in your eye, something ineffable and true and good. It was there the entire time. My future self will lie in bed and take comfort, smiling alone to my closing eyes, eased by the thought: I sensed the value of these workaday nothings not after it was too late but while they were happening. I knew the good time was good and how, and I am grateful.

0 Comments

I used to see these two often. Neighborhood stalwarts both, who each single-handedly elevated the community. Solomon, from Ethiopia, a fifty-something jolly fellow who wasn’t quite chubby, always with a ready smile, worked in catering, generally for high-end hotels. He had a lot of stories.

Ed was similar in age but thin, even cleaner-cut than the already put-together Solomon, slick in a working-class sort of way. He was black American, and I was pleased to see them chatting easily tonight, bridging the invisible divide that too often separates African and African-American cultures here in the Valley. They were old enough to not care about such things. “Sometimes I get up at 4 A.M.,” I heard Solomon saying behind me. They chatted for a while about odd hours and long shifts. Ed finally got up and said, “What's your name?” Solomon responded in kind and they shook hands. To my surprise he introduced himself to me as well– “I'm Ed,” he said, flashing a movie-star caliber smile. He then sat down and returned to the conversation. “But you know, we got to be thankful for havin’ a job. Not everybody is so lucky right now.” “That’s true,” said Solomon. A relaxed vibe colored the air; something not unlike the after-dinner glow, or the pleasing camaraderie of a campfire when you were young, as the older folks spoke together in calming tones. Ed said, “I'm 54, and my son is 26, great kid, and he gets up at the crack o' dawn every day to go to work. And he learned to do that by watching me get up at the crack o' dawn every day to go to work." "That's impressive," I say, "especially for a youngster." "It is. So it's not always what you say, but what they see–" "Leadin' by example–" "Yeah. I don't wanna sit here and talk bad about my father, but man, he was not a good example. The way he treated my mom, the amount of time he was ever around... but also, they say if you have bad parents you're destined to be a bad kid, but that's not always true. 'Cause you could be learnin what not to do!" Solomon: "Yeah. Yeah, we always learn, no matter what's goin' on." Me: "You're right, 'cause both my parents come from not exactly ideal family situations, but they're amazing people. They're incredible parents." "Yeah." "I never put that together before. It doesn't mean you're destined for failure." Solomon again: "'Cause they could be learnin' just by watching." Solomon got off, shaking hands with Ed again. Ed rode the Prentice loop with me up to his house. He told me a story, as he put it, of his father, who he'd seen only a few times in his entire life, how this father never met Ed's children or other relatives, though he lived only eight blocks away... the details are a wash. But I remember one thing: "He came and woke me up one night, shook me awake, he's standing over me in his military uniform and everything. He says, 'I'ma see you tomorrow.' He wasn't there the next day, or the next. I didn't see him for thirty years. I never forgot that, him saying he'd see me tomorrow." "That keeps me hitting me at the heart," I said, regarding that incident after he'd moved on to other subjects. "'Cause that's one thing I try to never do, is break promises I've made to kids. 'Cause that's a big deal. I mean it's a big deal with anyone, but especially with children. They don't forget stuff like that." "Nathan, it was such a pleasure talkin' to you. If you're on this line I'll be seeing you again." "I'm here all five days! It's my favorite route. I rode it a lot as a child, so it feels comfortable in a way for me now." "Say what they may about Rainier Beach, but up here..." We marveled at the view of Lake Washington. "Oh, it's beautiful up here!" It pains me that this is my only story with Ed. There were others, but I’ve since misplaced the notes, and the lines we exchanged are lost to time. I’m almost certain he is dead now, because I once came upon him and asked him how he was doing. I don’t need notes to remember what he said to me, over seven years ago: “Well, Nathan. I’ve had better days, but I’ve also had worse ones.” I asked him to elaborate, and he did. He’d just been diagnosed with a rare bone disease which was terminal, and carried a remaining lifespan best measured in months, not years. I was stunned. Ed, pillar of the community, loved by all? Ed, whose wife and daughters I’d met on the bus more than once, each joy-filled charmers as much as he was? He’d had worse days than this? I told him I was in awe of his fortitude and perspective. You’re a big deal in this community, I told him. I want you to know. People talk about you, and it’s only ever good stuff. I hear them all the time. He happened to have a folder with him, perhaps from the doctor’s visit, which also contained material on his community organizing work– he proudly shared some photo printouts of him leading a rally in the Central District, among other noteworthy items. I only remember glimpses of the conversations I had with him. How I wish I still had the notes. An evening ride up to the Prentice neighborhood as he told me of a decades-old memory seared in his mind: waking up to his father choking him in rage at night. And Ed telling me how he swore to never let his children feel any such terror, to ensure they would always feel safe and loved by their father, that he would be constant and regular as a loving presence in their lives. He had the knack for turning trauma into a learning opportunity, for stopping the tide of hate with love. People talk about doing that all the time. Most don't follow through. A couple months after this I would have trouble recognizing him due to how slowly he moved, grimacing in pain as he bent his knees to sit down. But as ever the resilient glow, despite the physical torment. He’d tell me I brightened his day, and I’d laugh in reply: “Ed, it’s you who’s doin’ the brightening! You make my day!” Several years later his wife got on my bus. To this day I regret I didn't ask her when I could about how Ed was doing. I was scared of hearing what likely was the answer. He gave me his number and encouraged me to stop by one of their Sunday family meals, and I cannot tell if my memory of once calling him really happened or if it's my own desperate wishful thinking. In 2013 I had no experience with Death. Maybe I would have made things worse. After a time Patricia began deboarding through the rear doors, and I felt for her; she carried a weight too heavy for strangers to make worse by bringing in small talk. The last time we spoke she told me of a venture she was starting up concerning women’s makeup and possibly hair. I mostly remember the anguish we will all eventually feel, the restless and tiring search to rebuild ourselves in the days of After. Oh, Patricia, if I could talk to you now. Will these words ever cross your desk? You and your daughters remain blessed to carry within you the spirit of such a great man, a man whom I know I am extremely fortunate to have known, even briefly. I hope this recollection does your husband justice. I know I'm not the only one inspired by his memory toward goodness. As I recently told another passenger: I don’t understand this world, but I like living in it. I hope you do too. 1. Maybe we should talk about it.

I’m aware that almost all operator assaults are fare-related, and that so many assaults can be causally traced back to an operator’s attitude, choice of words, or tone of voice. Nobody deserves to be assaulted, but you understand what I’m saying here. It generally takes two to tango. We mirror each other, and disrespecting someone, even in a way you think is small, can beget further disrespect. People can smell when you’re condescending to them, and it stings. Doesn’t it sting? Don’t you resent squirming under the thumb of a belittling authority figure? That’s how they feel in that moment. It takes two. However. Sometimes it only takes one to tango. I've had moments in my past where I know my tone contributed to how things went down. Where I should’ve bit my tongue or been more patient. This wasn’t one of those times. This was absolutely and incontrovertibly not one of those times. 2. Here’s what happened. I’m inbound at Broadway and Pine. The last passenger, a young white woman who smiles a thank you to me from the back door, deboards. As she is stepping out a young black man about her age– mid-twenties– of stocky build and, by the condition of his skin and attire, decidedly less comfortable in life– hops in. Blue hoodie sweatshirt, grey sweatpants, just barely unkempt. He waits briefly for her to step out. He enters the empty bus. He stalks up to the front. It’s Coronavirus season, and like all other buses in service, a velcro strap separates the front ADA seating area from the rest of the coach interior. He sits as near to the front as possible without crossing that barrier. In my head I think, interesting choice, coming all the way up here from the back door. Maybe he’s unsure of his destination and wants to sit close to the front. He hums quietly to himself. Since there’s only one passenger, I don’t call out the stops, except to say at 7th, as we approach 5th and Pine, that the next stop is 5th and I can’t stop at 3rd and Pine because we’re turning into a 7. He ducks under the strap and comes forward. Again I think, interesting. I wonder what sort of headspace would think that’s the thing to do. But I don’t say anything about that. I say, gesturing to the bus stop at 5th, “D’you want this one right here?” He says, “Yeah.” I feel a need to break the ice. To make friends. Let him know I don’t look down on him. I say, “How’s it goin’?” “Good.” “Cool.” Do you know how many thousands of times doing that has worked wonders for me? Solved problems before they even began? Do you know how many thousands of times that will continue to work for me, in the future? Innumerable thousands, that’s how many. Except not this time. We get to the zone. I open the doors. I say, “Thanks, man.” Then he changes into another person and explodes. He is spitting on my face four or five times, cursing in furious anger, now quickly exiting, stalking toward Westlake Park, looking back to see if I am following. For myself, I was so utterly shocked I didn’t respond at all. Events like this have a duration of seconds; the only way to get good at responding to them is to experience them regularly, which I don’t. I said, “Whoa, whoa,” trying to calm him, but I couldn’t form words to speak. Maybe that was for the best. What would I say now, if anything? I might try out Did that help? Or Tell me where you’re comin’ from. Or just Talk to me. These lines would have the effect of humanizing him, forcing him to engage emotionally. Which pissed-off dudes don’t like, because they can no longer merely be angry anymore. Why are you angry? They have to go back to being human, which means no longer spitting in people’s faces. 3. I believe this was premeditated on his part. Why else would he come sit at the front? Duck under the strap? He wanted to get back at an authority figure. He was coming from the direction of the occupied protest zone on Capitol Hill and was likely seething with anti-authoritarian anger. He wanted to fight the world. I had nothing to do with it. Why does someone in pain want others to feel pain? Why does someone who feels hated want to hate others? These are questions that answer themselves. He was a young black man who probably felt scared, hated by the broad spectre of an uncaring society, and who was definitely very unstable. Not a great mix. Like me, he seeks balance, and felt this would right the wrongs of society. He assumed I was part of the problem, because many people are. This has happened to me before. I remember an operator telling me afterwards, “I told the other guys in the bullpen, and we all just sat there dumbfounded, like: If this can happen to Nathan, we’re definitely screwed! You’re fuckin’ nice!” Don’t think that, friends. I’m grateful for the implicit compliment, but I need to reinforce that it’s still worth it to go out of your way being kind. Respectful. Loving. Patient. Compassionate, without expecting thanks, without expecting good treatment. Remember, passion, for most of the existence of the word, meant suffering. Compassion means to suffer together. Life is supposed to be a struggle, and we’re supposed to love each other. In 1871 George Eliot wrote, “What do we live for, if it is not to make life less difficult for each other?” Her words are still true today. This would be easier if I had been a jerk. Because now I would know what to do next time: Don’t be a jerk. Easy. But I didn’t do a thing to invite this one. This was a solo tango par excellence, and he had no dance partner at all. What, then, do I do next time? 4. Should I let this alter my approach? Absolutely not. Don’t sit there devastated in the bullpen, thinking there’s no point to being nice. Your strategy doesn’t have to work all the time to be worthwhile. My strategy, conveyed in all the stories on this blog, works 999 times out of a thousand. It’s not the only way to do things, but it’s a heck of a batting average, if I may say so. I will not allow him to make me forget that. 5. I will instead allow him to be small. A pebble in the roadway, not a roadblock. You can go through the worst hate, and survive– that means you’re More Than It. If you can thrive in spite of your traumas, you can do anything. You’ve heard the idea in philosophy: we humans are relational beings. What does that mean? We define things by their relation to another thing. What is night? The absence of day. What is light? The opposite of darkness. Have you ever noticed how dictionary definitions only tell you what a thing is by describing another thing? The implication is that there are opposites, contrasting degrees of existence, and that this is inextricably woven into the fabric of life. Because there is heat, there must be cold. What goes up must come down. I exist, and therefore my opposite must also exist. Who is my opposite? Or, more accurately and in accordance to how we think of things like day and night and hot and cold as balanced, as two sides of the same coin: Who is my equal? I think I just met him. 6. I have met my equal. I love people without reason. I don’t know why I’m nice. I just am. Am I crazy? Sure. So is he, who hates people with apparently the same level of fervor, and also without reason. I have met my equal, and I will force the tragedy of the encounter into a learning experience. I will gain something from this, some insight that brings me closer to peace. I will not let it dominate me with thoughts of spite and revenge. You never need to worry about revenge. The world does that for you. If he’s cruel to you, he’s also cruel to others and he’s going to meet someone who’s not as nice as you, who has nothing to lose by biting back. They'll do the hard work for you. Don’t worry about it. Worry instead about how to let this not take you over. How can you become stronger. Because: 7. Losing is when you learn. You don’t learn much from winning. Suffering is when you have a chance to bind yourself to something higher. Mercy, forgiveness, empathy. How will you strengthen your worldview without resorting to bitterness? Bitterness is easy. How will you accept the existence of hate as you continue going about your life, stopping the spread of hate and giving love instead? Doing your small part, and never mind what you can't control? You’ve been watching more news lately. We all have. Without telling you what to do, I’ll share a word from someone I trust: Imagine a person who is totally unaware of today’s world strife. Who knows nothing of current events. This person is kind, and compassionate, in all the ways the Black Lives Matter movement highlights the lack of. This individual goes about their life quietly, humbly, lovingly, treating others with grace. Does not this invisible person represent the ultimate end goal of all our social movements, and is (s)he not better equipped to be the positive, life-affirming human (s)he is because she isn’t infected with newsmedia devastation dragging her spirits down? Food for thought. I went to a lot of protests in college. I have similar if more nuanced views now, but I feel my role is better cast as following the example of this hypothetical individual above. That is what I excel at. I admire those who represent similar hopes for progress in more confrontational ways, but I have drifted toward a quieter and more personal method of embodying kindness. I wonder if our friend on the bus will similarly soften with time. We're all trying to figure it out. Unrenovated Fred Meyers will always have a special place in my heart. There aren’t many left; I only know of one, in Lake City. The layout, the font, the aisles and floors and widths and arrangements… these are the ingredients of my childhood, and they comfort me.

The American allergy to the past pains me because of its relish for erasure. It removes my ability to touch my memories, or feel the truths of an earlier time. I came of age in such spaces, and find myself in a reflective state when in them, able to think in the language of decades. There remain only a few locations that look like they did when I was a child. I treasure them. It was while in just such a headspace that I stood in line at the Lake City Fred Meyer, observing the beige background behind the tuscan red sans-serif lettering which denotes what lies down each aisle. “Chips. Cookies. Peanut Butter.” Sublime. “Bath Tissue. Cleaning Supplies.” Ah, heaven. Echoes of a time when form followed function more regularly than the other way around. Isn’t it delightful? The non-slip flooring, a collection of unglamorous off-white creams and tan streaks, the better to hide debris; the shopping carts with the green handlebar, which I knew intimately the feel of, the durable plastic flattened at an angle facing you. How my childhood hands would grab and hold as I turned the cart down the aisles. Or the unsophisticated layout, navigable and plain, under signage with no need for stylish flash; does everyone find themselves so heartened by such details as I? Or is just me and Seattle Walk Report, whose illustrated enthusiasm for minutiae articulates these joys in ways both richer and lighter than words can ever touch? Earlier spaces tend also to be less shamelessly obsessed with taking your money. But more broadly, the passage of time writ on a space is one of the few reminders of mortality that is pleasant: we take comfort knowing we, too, have similarly survived the vagaries of time. I looked at the person standing in front of me in line. She was dressed in a white habesha kemis edged in blue trim, with a netela wrapped about her head. Her face was exposed but turned away from me. Was it her? The bouncing ball of joy I used to drive to the Ethiopian church in Judkins Park, who cleaned airplanes at Sea-Tac? Her ebullient character was one that stuck in my mind for years after last seeing her (the story linked above happened in 2014). The sort who makes friends easily, and is no doubt well-loved in her community. People love those who bring out the light. “Hi,” I said tentatively as she was half-turning to look at something. “It’s Lamlam, right?” She needed no reminder, no clarification. Her eyes immediately went wide with animated recognition. “Hiiiiiii!!” Lamlam outstretched her arms and before we knew it we were hugging tight, the way acquaintances instantly become good friends when meeting on the other side of the world. I’d never seen her this far north, so far away from her old haunts, nor off the bus; but here we were now, neighbors in life. She was thrilled. We asked about each other’s jobs, where are you living now, do you still do this or that… but mainly we sang in the voice of community and belonging. I found myself seeing the scene through the eyes of the cashier, who was watching our merriment with delighted surprise. She was a young woman who wasn’t expecting two such culturally contrasting customers to suddenly explode as one with glee; a demure Ethiopian woman in traditional attire on the cusp of middle age, and some young lone westerner in boring clothes. What could they have in common? Everything, as it turns out. The cashier’s elated wonder only added to our jubilance. It became the three of us as I explained how we knew each other, and now we were a trio watched by the rest of the line, showing them what’s possible. At the center of it all was Lamlam, a beacon who loved and felt loved in return, who lived in the easy burgeoning newness of a present she made. Such people are inspirations, especially when the world feels like it’s collapsing around you, losing all semblance of what’s recognizable. There will come a day when I won’t recognize the interior of any Fred Meyer, or perhaps any store, I walk into. I will feel lost, as I sometimes already do, losing ground on a shrinking island as the world becomes less familiar. I hope then I’ll still carry this memory. Maybe all that will remain of it will be her smile, preserved in something akin to a photograph: Lamlam making the world glow. I hope that’s enough to remind me that I don’t have to be a product of my environment, but my environment can be a product of me. I remember being secretly excited, the two of us talking together on a midnight 41. Who started it? Probably him, but I was only too happy to oblige.

I was in the first forward-facing pair of seats and he was three rows behind me, on the bench over the middle wheels. Not at all conducive for conversation, this arrangement, but somehow it turned into the perfect setup. People want to reach each other. We wish for feel connection, belonging. He was a black man a decade older than me, but otherwise not so different– another skinny man in urban America, apparently prone to smiling, similarly getting more pleasure out of talking to someone than not. We talk to each other because deep down the void of mortality and the necessary loneliness of death scare us, and we wish to sit closer to the light. To feel something besides the solitude of impending death. --- I said, “That looks like a pretty warm coat though. You got the fur up there.” “Yeah, that's pretty much it though. All I got’s a T-shirt under here. I dunno how these guys do it, lyin’ on the sidewalk like that. With the wind comin’ in, I feel it cuttin’ right through me.” “Especially how it comes in between the buildings!” “Yeah between the buildings! And here’s dudes just everywhere just layin’ around sleepin’. I’m from Florida. All these folks would be in jail if it was Florida.” I raised my eyebrows. “Really?” “Yeah," he replied, building with the enthusiasm of sharing. "They give you a citation the first time, tell you to pack everything up. They book you three times it’s a felony.” “Whoa. A felony! Then you can’t get a job!” “Tell me about it!” “Man, here people can throw up a tent on the sidewalk and leave it there for weeks!” “All these folks would be gone. The streets would be so clean. If it was Florida they build a big huge prison to put all these people in. As soon as they come out, they put ‘em back in again.” I couldn’t divine his opinion on the situation. We’re so accustomed to truth being wrapped up in editorializing these days. For myself, I couldn’t help but think such draconian efforts toward a clean sidewalk weren’t worth the damage it caused those downtrodden lives, and said so. “That’s kinda scary. The way it sticks with you, on your record, and limits your future prospects.” “It is,” he said. “What I don’t get is, there is so much opportunity here. Why’re these people just layin’ around? This ain’t like Florida.” “Seems like more job opportunities here for sure.” “Not just job opportunities, jobs period. Man, here in Seattle you just look in the direction of a job, and you got one. You could flip a burger and get $16 an hour for it. All you gotta do is step up! I been workin’ with these dudes now, gettin’ on good terms and all, and now they gon’ pay for surgery to get rid of my face tattoos!” “I was gonna say, nobody’s gonna mess with you!” He laughed. “Ha! Well, it ain’t a prison thing. People look at me and they’re like, what’s…” “What’s the story here!” “Yeah. But no, it’s just a look. I tried to do music, but it was too expensive. You need money for that line. But you just meet the right people showin’ up and gettin’ it done.” I nodded. “People respect people that put in the effort.” “I been working grocery stores since I was eight years old. I’m forty-five now. How hard is that, bagging groceries? And here, you get paid. Minimum wage in Florida is like, $8.25. And did you hear, in parts of Tennessee, it’s still $6 somethin’.” “Okay wow. Wow. How do they expect anyone to get ahead?” He said the next thing as if it was normal. “Especially if they get you for jail. They charge you $35 when you go in–” “Hold up.” I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. “They charge you to go to jail?” “Yeah! Thirty-five to start, and $20 for the wristband–” “What?” “Thirty-five to go in–” “Hang on. My head’s going to explode.” I was fully turned around in my seat now, facing him. “They pick you up off the street, against your will, and book you, and then they want your money?” He grinned with a shrug. “I’m tellin' you man, Florida! And it’s $1.50 a day for meals, or $1.50 or $2 depending on the prison–” “–for terrible prison food I assume–” “Yeah. Donations, mostly.” --- I got up and went over to sit across from him. He had an easy vibe, the knack certain people have for making you feel comfortable, no matter their appearance. I must have sounded so naive, but I had no idea. I’ve never been arrested in Florida. “I can’t get over this. You have to pay money to go to jail?” “And if you can’t afford it, they hold that debt against you, as a further reason to keep you in longer. A lot of them have farms attached to them, and they make the prisoners work the farms if they can't pay the fee.” “That’s slavery.” “Ah know!” “That’s– man. That’s completely the same as... I can’t believe this. In this day and age, the…” He shook his head, a rueful smile. I said, “It almost makes it worse that it’s happening now.” “It does, don’t it?” “I mean I was aware they unfairly imprison tons of people for free labor, but I had no idea they were charging people money on top of that. How do they expect society to keep runnin’ if they’re just throwin’ everyone in jail all the time…” I realized I was answering my own question. “...And keep charging them all this money?” I sighed. “And the whole $8.25 an hour thing, that just keeps people forever unable to rise out of their situation.” “Exactly!” “The system keeping them stuck, giving them no option, nowhere to turn to. That’s a nightmare!” “The cops are in on it, the judges, the public defenders making money off of all this. The amount of corruption–” “At every level–” “Yeah!” I remembered Angela Davis’ term. “Like an industry.” “That’s exactly what it is. You could have a seed, a single seed of hash and they got you booked.” “Man, how do you fix a system that’s that bad. Seem like the only thing to do is just get away if you can. I am so glad you got outta there.” “It’s not a lotta liberals down there.” “I’d be the only one!” “Ha!” --- If some of a society is held back, then all of society is held back. No matter who you are, you want others to do well, because that will help society at large. Maybe this is old news to you. But let's say it isn't. In the name of doing something besides preaching to the choir, I speak now to those unconvinced by today's calls for decency. Let's say you don't care about poor or marginalized lives, and are preoccupied only with your own success, unconcerned with thriving off the suffering of others. Fine. Even if these are your views you still want others to do well. Why? Because it’ll elevate your quality of life. Land for agricultural output used to be the ultimate and primary commodity, and because it was limited, competition for it at the expense of others was binary. A zero-sum game. Your doing well necessarily meant others doing poorly. But the world today operates on what's more accurately termed a non-zero-sum game– there are numerous commodities with ever-expanding means of delivery. Binary competition is becoming outdated. Other people don't have to do poorly for you to thrive. Innovation increases with greater demand, fed by a supply of more people with similar problems to yours. If more poor people and people of color can get good educations, that means there are more scientists developing cures for cancer. You want that, when you’re coming home from the doctor with a report in your hand. You want a larger pool of bodies solving problems and creating, thinking, inventing, researching, and engineering together. If more people on the street can get housing and drug counseling, that means less entry access points for impressionable youth– your kid– to get involved in addiction. Even if you believe you have no connection to street people or the working class... you still do, and you want them to prosper even if you have no empathy for their circumstances. Because their doing well will help you. --- Further reading: I sound like I'm advocating for ethical egoism and egoistic altruism. I'm not. Those advocate for prioritizing your own self-interests over others. I'm speaking only what I say above in terms of social contracts and how caring for others can benefit all, without trying to sneak in political agendas. Further context:

I find things to agree with in both of these diametrically opposed views:

More on pay-to-stay prisons:

For whatever reason all the boys in sight had basically the same haircut: a semi-close shave on the left side, and on the other side, longer hair with fashionable curls, echoes of the flapper girl aesthetic. It was an absurdly specific hairdo to be so ubiquitous, but there you go. Apparently it was all the rage in 2015 southern Italy. I was traveling alone, late-twenties restless, eager to feel for myself the truth of Hugo’s immortal words, the best yet written about travel:

As in the morning, he saw the trees pass by, the thatched roofs, the cultivated fields, and the dissolving views of the country which change at every turn of the road. Such scenes are sometimes sufficient for the soul, and almost do away with thought. To see a thousand objects for the first and for the last time. What can be deeper and more melancholy? To travel is to be born and to die at every instant. No other experience more closely approximates early childhood. The bombardment of stimuli, languages you don’t understand, every word and color something new– settings where memory is insufficient to comprehend existence. That is where I was, and where I needed to be. We are taught how to think, but not how to feel; any life event involving emotions is one we stumble through, amateurishly. Travel forces all at once upon you a concentrated heap of life experience. I drifted through the cluttered square, an open oblong plaza from which extended five or six ancient cobblestone streets heading off at odd angles. You felt a weekend sensibility here, adolescent gaggles of arms and legs and dreams. Must have been school break. Do you remember what it meant to be that age? Timid and loud together? I rode the subway into town and they were everywhere. I imagined similar scenes on the other subways coming in. These were the nights of possibility, humid air rife with hormones and longing. Even in Napoli, people look put together; this is still Italy, after all. I was by far the worst-dressed person in sight, with my stocky black raincoat, unwashed hair, ill-fitting black jeans and dirty boots. I hid my film camera in my coat and tried to keep a low profile. Tourists don’t come here. I did what I often did as a lonely child, and what I’d come here to do: observe. Observe, reflect, and create. I wandered aimlessly through the square, my thoughts drifting along the above lines, when it caught my eye. The only English language wording in the entire space, in this burgeoning chaotic plaza with its teens and cars and signs and stores and vendors and alleys… was a phrase penciled in sharpie on the side of a girl’s right shoe– on the welt, to be exact, the bottom outside wall just before it touches the ground. The welt of her shoe was white, and the black sharpie thusly caught my eye. She’d scrawled in neat, bubbly handwriting a line from a song I knew well, new at the time: You’re so Art Deco, out on the floor. Lana Del Rey’s sultry voice, with its strangely energizing despondency, wasn’t literally playing, but in that scrawl it flitted through the air like a whispered secret, at once giving the plaza rhythm and making the whole place wink. We are like you, the wink said. Our hearts are the same shape as yours. A woman was performing on a sidewalk portion of the open space. She stood beside a seated musician who accompanied her singing with classical guitar. He didn’t make much of an impression, perhaps the better to let her shine, for shine she did: she resembled the older Sophia Loren of Ettore Scola’s 1977 Una giornata particolare, with the same grace of self, the poise that comes with age and deepens your beauty. This woman’s dark hair was longer, and her voice rang out elegantly, if wearily. The kids paid her no mind, but occasionally a soul would pause. I took up a position across the street and watched from a distance. She sang what sounded like Italian traditionals, and the melancholy chords they required she suffused with histories of pain comprehendible in any language. What was her story, this striking figure who'd surely lived more than the street performer life in which she was now engaged? Her presence spoke volumes, and by the time she was wrapping up had attracted a small crowd of listeners. Some left a few coins as they scattered off. I approached, and she looked up while boxing up her microphone and related paraphernalia. I wasn’t surprised to discover her face up close as captivating as her voice from across the street. Some people disappoint at close quarters, or reveal themselves as different than you assumed; she was precisely the person her voice proclaimed her to be. Deep emerald eyes matching her flowing dress, a contrast to olive skin that had seen better days. I fumbled with my Italian, but she knew some English too, and caught my meaning. I needed to tell her how good she was. I needed to contrast the ignorance she received from the others. Most crucially, I somehow needed to express that she wasn’t alone, that I knew something about the debilitating solitude of crowds. We communicated most in the silences between our words, in the universal language of looks and gesture. I gave her the handful of coins I had left, knowing it was a hefty quantity of money for pocket change. I complimented her singing and spoke my appreciation of her being here tonight. We looked at each other, divided by generations, culture, geography and language. We held the moment, knowing we’d never meet again. You can dream an entire life in an instant. I dreamt of a world where she was appreciated by those around her regularly. Where love played a greater defining role than struggle, and her loneliness was assuaged often and with ease. I could observe by her surprised gratitude toward my kindness that such things were not customary in her life. Nothing makes us belong more broadly than a meaningful encounter with a stranger; the moment we exchanged made me feel part of something shared, something vast and knowable. We’re all in this together. I hope she felt similarly. --- This is a spiritual sister to this story, about another evening moment in Western Europe, this time in Paris. His friend was scrambling about his pockets for loose change when the first young man yelled with gleeful abandon,”Dis nigga don't care!!”

Meaning, this driver is sympathetic to your cause, and prioritizes larger concerns! He looked exactly like Mos Def. The two of them sat together before the friend dipped out at Othello Street; Sir Def remained, a young man at the end of the evening, headed home on an empty bus and with only his thoughts for company. As we passed Graham I peered across the street to see if Vern was panhandling outside the 7-11 gas station. He was. I double-tapped my horn in a friendly honk, getting his attention and waving large. Vern lit up on recognizing me and returned the wave. “Is that Vern?” Mos Def asked. “Yup! Cool guy.” He grinned. “I think you're the only bus driver who does that.” At first I was going to disagree, out of humility, but then I had to admit it even to myself: Who else is going to wave at Vern? And who’s going to take the trouble of honking the horn to do so? Nobody, that’s who. I smiled. “Probably, yeah!” After a pause, I said, “I'm too nice, I can't help myself!” It was an admission of kindness, vulnerability. If Mos had still been with his friend, I don’t know that I would’ve said anything. But on solo terms you can go a little further. Sensitivity can live a little larger this way. He grinned in understanding. “Naw, you just part of the neighborhood!” he said, appreciatively. He settled further into his seat and looked out the window. Thank you, world, for making room for someone like me. For letting me exist, even thrive, from time to time. I used to think fitting in was the way to survive. Learning the opposite is closer to the truth has given me more peace than I can relay here. You go out there as your best self for long enough and you begin to notice Like attracting Like. You bring out the light in others. Not every time, sure, but often enough to make it worth it. Because we do such things for ourselves, really; the others can react as they please. I'll wave at Vern because waving at Vern makes me feel good, even if he doesn't notice. But I won't deny it's a cherry on top that he saw me tonight. --- Meet Vern here: Vern One. Sure, why not, I thought. There's no one else out here.

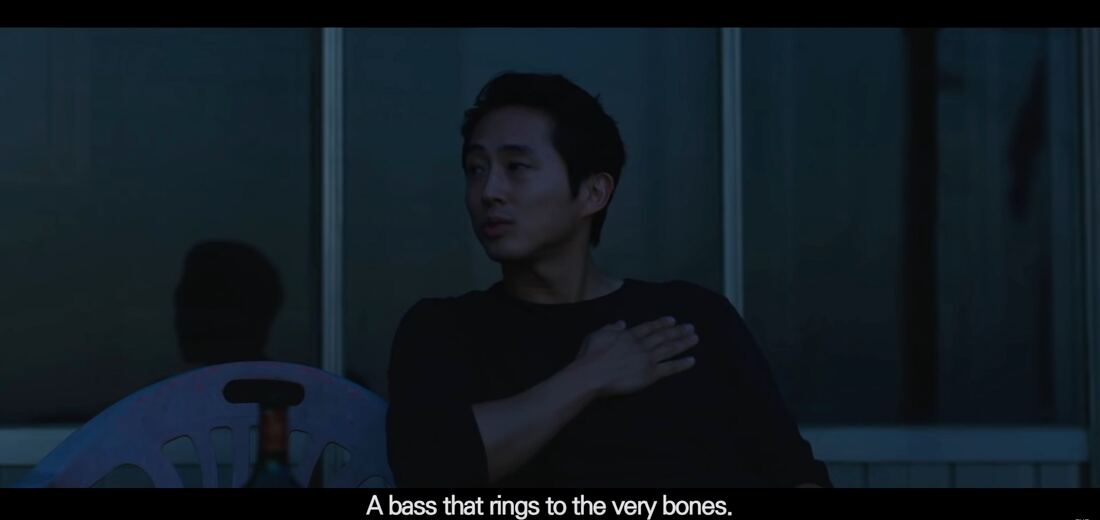

I stopped in the middle of the block to let two runners into my empty bus. It was the end of the evening, my last trip on another late night heading down Broadway. “I appreeeeeciate that,” said the first man. The second looked up. “Thanks bro– oh, hold up! Yo, this guy is famous.” “Aw yeah!” “He's the friendliest, most incredible–” At this point I had to interject: “Nawww!” “Bro, I'm for real! Shit, no wonder he stopped for us, that's why. 'Cause he's the hella cool famous guy. Check it, this guy, man. He don't never lose his cool, always good to people, relaaaxed.” His friend said, “I bet he got people fightin' for him.” “He be like, come on in. You got two dollars or two pennies, don't make no difference, he still gon' be nice to you. Listen to me, my dude. You're doin’ God's work.” “Thank you!” I said. “For real. Cause it'a be some bus drivers you try to pay yo fare, I seen this one guy he had a dollar forty and he ask the driver for a transfer, he done already put money in the thing and the driver say no! What that guy supposed to do? He don't have no money left!” “He shoulda just walked right past him,” the other fellow remarked. “Drivers pulling that type a shit it ain't no wonder people walk right past!" I sympathized, but I had to clarify a point: "I appreciate it when people ask me though, ‘cause they know they could just walk right past and I'm not gonna do anything, but they ask anyway. Which I love, cause it's outta respect. They don't have to pay, and they know they don't have to say anything. But I love it when they say hey." "You know that's true," he reflected. "Yeah it's cool when they actually say something. Not like them dudes that be steppin' on like they own the motherfucker. Walking all up in here like the bus belongs to they ass! Some uh these guys makes me laugh, bro. Hey, like this like this." He stood and began pantomiming what Tom Wolfe calls the pimp roll, the expressionless swagger we would chuckle at more often if it wasn't always carried out with such desperate earnestness. I was laughing. We all were. It was great to see someone sending up the self-serious obsessiveness of certain street attitudes. A relief. Particularly because these two men, dressed as they were, speaking in the vernacular that they were, of the race and socioeconomic class they were– came cloaked in expectation whether they liked it or not. They were the sort you expected to be doing the swaggering, not calling it out. But the world is more complex than any stereotype could ever dream of. I said, "You know exactly how it is!" "These niggas be rollin' on with this fuckin' stone-faced killer bullshit like the world owes them a mothafuckin' ride! Like the rest of us is working for they punk ass! I pay my shit every month. I put my shit in the mail. But these dudes, oooh no. They be swaggerin' on in without a word like they built this fuckin' city! Shit is hilarious, dogg! Yeah, you right, those fools could at least say hey." "Some kind a connection, human to human!" "Yeah, it's disrespectful. It makes me mad, but it makes me laugh. You got to laugh. And then they be like, 'I'm old, I'ma need you to get the fuck up outta them front seats! Yeeeah. I'm a need a seat right here, nigga, what choo gon' do?' Steppin' at me like this. Walking in like this, and then like, 'you need to get the fuck up.'" Reader, how can I explain how completely hilarious this was? I've never laughed so hard at one in the morning. He was mock-behaving the role as he described it, acting it out in the most exaggerated manner possible. The narrow, hypermasculine template of existence embodied by certain young black men is notable– like all modes of hypermasculinity- in taking itself almost absurdly gravely, and each of us was so intimately familiar with such solemnity as to make his parody of it absolutely hysterical. His version of a self-serious teenager swaggered so hard it bumped into the stanchions, and his guttural verbalizations ("Sup.") were an outsized riot. He cocked his head back so far while trying to maintain a forward gaze he was practically looking at the ceiling. "'You need to get the fuck up so I can sit my important ass down,'" he was saying, by way of illustration. In his own voice he added, "And I get up. 'Cause it's what you do as a reasonable person. You get up. People get up. Shit like that ain't worth bothering with. It's stupid bullshit but it's funny as fuck too. You gotta laugh. Anyways. We appreciate you drivin’ the bus how you do.” “Young man making money,” his friend said. “Keep it up!” “I never get to see this cat anymore. This nigga here,” the first said, shaking his head toward me in admiration. I had finally calmed down from laughing. “You guys were the highlight! It was a beautiful day in the neighborhood, but you guys were the highlight! Thanks for stoppin’ in!” “Always!” 'Cause it's what you do as a reasonable person. I appreciated hearing that. Sometimes certain attitudes drive you up the wall. They're designed to. Don't give in, because like he said, it ain't worth bothering with. If the interaction is in passing, consider giving them what they're doing a terrible job of asking you for: Respect. That's the only reason people pull such ridiculous behavior. They're not getting respected, or acknowledged, or loved, or all three. And so they try to demand it. They don't know what you already know, and what will get them into trouble later: merely acting like a king won't get you treated like one. But giving them what they have no idea how to ask for might soften them a little, keep them from needing to shove their bravado in your face so much. Respond like reeds blowing in the wind, bending instead of breaking. Maybe they'll learn they can bend too. "I feel a bass, right here. A bass that rings to the very bones." dir. Lee Chang-Dong. Synopsis: Jong-Su meets a woman who may or may not have known him from long ago, and whose friend Ben may not quite be what he claims to be. Cannes Trailer. 148m. 2.39:1. --- What is the significance of living? Anyone who saw this Cannes entry and also saw the film it lost the Palme d’Or to– Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Shoplifters– should by now agree that a mistake was made in the handing out of cinema’s most respected trophy. While the excellent Shoplifters is no Green Book, there’s no denying that one of these films uses the language of camera movement, mise-en-scene, color, light, soundscape, editing and pace– in short, the language of cinema– to communicate to us viewers, while the other uses… basically none of these, sticking with acting and writing and not much more. Acting and writing derive more obviously from other art forms, whereas the tenets of cinematic form take better advantage of the medium’s potency. With all due respect to Kore-eda, a director whose purity of perspective and lack of irony I genuinely love, the Shoplifters approach is closer to watching (really good) theatre. Burning is a different matter entirely. It creates a mood that cannot be replicated in another format, because it uses tools specific to cinema. Burning does more than utilize the tools of Pure Cinema though. Director Lee (actually pronounced “Ee” in Korean) draws us in so much by leaving a lot out– we ponder all the further, studying every movement and moment for clues... to what, we are not even sure. The less you know going into this one, the better. Suffice it to say that it’s worth setting aside 148 minutes for something pretty spellbinding. I haven’t leaned that far forward while watching a picture in years. The explorations of the movie reach beyond the already compelling question of what the relationships are between these three people, and far beyond the already hugely compelling question mark of whether or not one of them is a criminal. A young man meets a woman he doesn’t recognize, but who remembers him well from childhood; she leaves and reappears with a man of mysterious origin who seems in every way his opposite. One is unable to experience human emotion; another watches everything but remains inscrutable; the third is hungry for a plane of understanding the other two can’t seem to fathom. And yet despite all these unanswered secrets, the climactic act of the film feels violently necessary, even appropriate, on levels we cannot articulate. Just watch it. And don’t read further unless you’ve seen the picture! SPOILER TALK: On Withholding Haemi’s comments about mime, and her search for something that transcends the entirety of the spectrum upon which either end of Jongsu and Ben sit, gain new meaning in light of her subsequent absence. Even an aside like “cats have a hard time changing their environment” becomes evocative in retrospect. When Haemi dances to the twilight and Miles Davis's score to Elevator to the Gallows, she seems to be ascending to a higher plane that is hers alone to touch. When Ben begins talking about burning down greenhouses, we are intitally shocked by the utterly unexpected nature of his comments, almost amused, but upon later guessing what he was referring to, chilled by his nonchalant attitude, just like those yawns of his that in retrospect strike one as disturbing. Ben seems to represent so many different things that are fundamentally wrong, and Jongsu’s violent act at the end seems borne of a deep-seated need to forcibly reject all of them: Ben's lack of human emotion, the social inequality he represents, his ease of lifestyle during a time when others struggle to get by, the very concept of uselessness, and his apathetic and potentially murderous blankness, his amorality. I appreciate the film withholding certain details, and notice it plays differently on subsequent viewings: we now know, for example, that the nighttime phone calls are his mother. But certain moments– Jongsu sneaking up on Ben by the water reservoir, with lots of buildup but which we never learn the consequence of; the fact that other women in the film wear a pink wristwatch, casting doubt on Ben’s unproven guilt; the suspicion that we may be seeing Jongsu’s writerly imagination, given that the scene of him at his typewriter sits adjacent to the only scene in the movie he’s not in; Jongsu’s uncharacteristic confidence in telling his mother he’ll “handle it,” whatever the problem they’re talking about is; the unseen cat, and so many more– these, as ever, draw us in even after the film is over. Ephemeralities I think the question of whether or not Ben is really up to something sinister is less a question than the strongly felt truth that there is something wrong about him, something criminal in spirit, that Jongsu can sense. Jongsu also seems often to be on another plane, one that the worldly Ben cannot understand. I find it fascinating and very nearly endearing that Ben is reading Faulkner, sincerely trying to understand Jongsu, because Ben feels he can understand everyone else but somehow not Jongsu; and that Ben seems to feel genuinely upstaged by Haemi’s comment that Jongsu is her closest companion. Ben has achieved all that mainstream society would call ideal, and yet, when faced with Jongsu, is faced with something completely outside his capacity to understand. Says actor Steven Yeun, who plays Ben: "[Lee and I] didn’t try to understand Ben from a material, physical level, but from a deep, philosophical one.” I like wondering about whether or not Jongsu, who often seems “slow” or dense, is in fact quite a bit more perceptive and in tune to something higher or larger than he lets on. The fact that this is never confirmed as such makes me lean in even more. There seem to be scenes which exist for the purpose of having us ponder the question: him looking up at the ceiling during his father’s courtroom arraignment; him walking out during the group job interview. Viewers of Lee’s films will know this is a recurring theme– a character who possesses a socially undesirable trait, which elevates their perspective in ways invisible to those around them. On Language There is also the question of the phoneticization of the title. There is a Korean word for “burning,” but this title uses neither it nor the Japanese one from the Murakami short, but rather Korean characters phonetically spelling out the english word: “baw-ning.” One other word in this film also receives this treatment, in arguably the film's most important dialogue exchange: “the Great Hunger.” Haemi even points out that what she’s describing are not the regular words for appetite, starvation, yearning, or craving, but something a concept beyond the definitions these words contain. Same with the title. Speaking further of language, Korean speakers will note how jarringly quickly Haemi switches to the informal tense with Jongsu, as well as the absurdity of Ben continuing to use the polite formal with someone of infinitely inferior social status during all of their interactions. He comes off as even more condescending than if he were using the informal or “rude” suffixes with this new stranger. Many films remain elusive for much of their runtime only to let all the wind out of their sales by explaining their secrets at the end (oh, Midnight Special). This one holds its cards close for its entire length, begging us to continue mulling things over long afterwards. This pervading sense of unknowing, coupled with the Korean language, which I as an amateur speaker I enjoy parsing and trying to keep up with, caused me to experience a sense of hyper-observation and attentiveness to detail at a degree beyond how I watch most films. Multiple viewings, incredibly, only sustain the pervasive mood of ambiguity. Lee’s knowing just what to show and not show, in all his pictures, I think, must strike a Korean viewer as particularly unique, given the new Korean cinema’s tendency to be too extreme, too transgressive (and for me often unwatchable), simply for the sake of being so. Isn’t less always more?

Northbound 4th and Royal Brougham, after hours. It’s always darker over here, a zone hidden in the open wastelands of industrial warehouses and vacant business parks.

He saw me from the bus shelter and scrambled into a standing position, torn with indecision about what to do with all his belongings. A collection of bags and buckets scattered about in his periphery. I opened the doors and leaned toward him. “Hey, my guy! D'you wanna ride?” “I do, yeah!” “Cool! Come on in!” “Uh kay, I just gotta grab all this stuff.” “Can I help carry anything?" He looked like a bruised animal, confused you'd ever want to pet it. “No. Thank you though.” “Right on. Well, I gotta keep it rollin’, so come on in!” “For sure. Thank you so much. Man," he said as he got everything, "You're the first driver...I been standing here four buses passed me by, cause I couldn't get my stuff ready fast enough. Which I understand, but it's like–” “Man, I'm sorry to hear it.” “Just blazed right on by.” “That's not cool.” “Worst day of my life,” he sighed. “The number of things... You know, you're the first– you're the second person today who's been kind to me.” “Aw man! Well I'm glad to be number two! We'll see if we can get it up to ten!” “Ha! I don't think that's…” he paused, realizing pessimism wouldn’t help things. “Well, thank you!” “Of course, always!” He plopped down in a seat with the relaxing finality of a hard day’s work done, or at least a tough rite of passage completed. On to another phase. He was a forty-something white man with reddish-brown hair and dressed like his belongings– equipped for the elements but corroded by them, sweatshirt coat and hood with blackish gray carpenters, the kind of nondescript outfit that leaves you looking for their face, the only revealer of who they are. I remember defined features, ready blue eyes and a goatee. “This is a great ending to such a shitty day! I'm not even gonna get into it.” I looked at him in the mirror. He was sitting halfway down the first half of the articulated coach, but I didn’t mind yelling. It was the relaxed atmosphere of the night bus, and the uncrowded air felt supportive. “Well, you know how sometimes a bunch of bad things happen all at once, and then a whole bunch of good stuff happens right after?” He nodded. “Yeah totally.” “Maybe it's like that, and the good stuff is about to come around!” “Right ON, man!” “All's well that ends well, right?” We went on like that for a while. Going through town we began filling up; the northbound 5 gets a crowd no matter the hour. I heard his voice again, talking to a seatmate. “You talking ‘bout the bus driver? Oh I know. He's the bomb.” “Best there is. I just got passed up by four buses didn't wanna wait for me. What am I supposed to do, you know? Wait for the nice ones to come around!” They were trying to keep their voices down from my hearing them. I smiled to myself. Here’s another friendly face stepping in at Pine: “Hey, amigo!” “Hey, Joe!!!” “Nathan! What're you doing on this thing?” I never drive the 5. Except right now. “I know, what am I doing on this?” “You're goin’ out to the boonies!” Chuckling: “It’s not my territory! I don't belong!” “Ha! You got no protection!” Later, Joe says: “All right, Nathan!” He’s yelling by the middle door. Somehow, and uncharacteristically for the normally quiet 5, friendly outspoken banter is allowed tonight. “Good to see you, Joe!” He’s gathering things of his own too; a theme for the ride, apparently. “Sorry I'm taking so long.” “Oh you're cool. You got it.” A Chinese woman deboarding now, with glowing eyes, says to me: “Shyeh shyeh!” I can’t summon the reply fast enough and default to English– “Thank you so much!!” Her husband follows behind her, gesturing to me with hands in supplication. The amount of gratitude we’re throwing around in here. It plays like a dream that shouldn’t be allowed to be happening but is, like those television shows from childhood where everyone was so nice to each other– except real and big as life, pungent with the unfakeable energy of the urban night. The guy who started this whole hive of goodness has been watching me. “What's your name?” “My name's Nathan, what's your name?” “Scott.” “A pleasure!” “You made my day man, and I didn't think it was possible! All this, during a crowd getting on… Listen, have a great night. Thanks for everything! Got all my stuff…” I could still hear him singing my praises outside. I don’t deserve this, I’m thinking, but I’ll take it, and gratefully. Deeper up on the route an older gent came forward. He’d also watched the proceedings earlier. “How many nights do you work?” “Five. I'm here every day except Thursday and Friday.” “I haven't seen you. I did just move to this neighborhood, though.” “You know yeah, I'm usually more of a south Seattle guy myself. This is new territory for me.” “Well, there's just one thing,” he said, winking: “Nobody on this bus likes you!” We fell apart laughing. I smiled for days. On to the next stop... |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed