|

When I was writing reviews in Hollywood, I was determined to avoid a pitfall I saw even in the most cultured and perceptive reviews- namely, a tendency to synopsize, and a tendency to avoid discussing aesthetics. Synopsizing bores me because what a film is about isn't what makes it good, or interesting; as Roger Ebert famously said, "it's how it's about it." The Godfather is not a good film because it's about mobsters. It's a great film because it universal themes of filial duty, love and death, using richly developed characters and tremendous directing and acting. It elevates the mob movie to the level of myth, with those rich, shadowy brown and gold images, and in its approach becomes a film about the American ideal and what it does to the soul.

All that will not be conveyed by simply recounting the story points. As well, to try to discuss a film without considering its use of form is a gross oversight. Cinema is a too complex an animal- often, as with To The Wonder below, a tremendous amount of meaning is communicated not through binary elements like dialogue and performance, but through composition, camera movement, choice of angle, color, music, and editing. Editing is what separates film from all other art forms and makes film unique- nowhere else can you juxtapose moving images next to each other. Directors know it is the tool for communicating to the audience: by placing one shot after another one, you're creating a third thing- meaning- that wouldn't exist without the juxtaposition. However, it's also unquestionably the part of the process critics discuss least- most likely because they come from backgrounds other than film (typically journalism or English instead), and either don't fully comprehend its value, or lack the terminology to express it. Sometimes filmmakers make the best critics. Just sayin'! Listed here are my top three films of 2013, with the links to the remainder of the list below. 1. Le Grande Bellezza (The Great Beauty) (Sorrentino) A one-time writer in his sixties lives comfortably in Rome's party scene, finding beauty underneath the surfaces of a chaotic life. Trailer. Most feel-good movies, like comedies and romantic comedies, or inspirational sports pictures, end on a note that feels temporarily satisfying... and also hollow. We know real life is more complex than what films like these show, and the feeling of goodness they engender passes quickly. The Great Beauty, about a still-popular writer (Tony Servillo, regular Sorrentino collaborator) trying to decide if he should write again, ends up being a feel-good film as well, albeit by way of a circuitous route. But the goodness it instils within us is different: it is grounded, and deep. We feel great about life afterwards, not because we've been distracted by falsely hopeful images, but because we feel a truth of fundamental value has been revealed to us. The realization the protagonist experiences at the conclusion stands to me as one of the great moments in film, because it is one of the most valuable insights a person can have in this life. I'd like to give it away so as to discuss it more concretely, but I leave that discovery to you. I'll instead mention how much the film lives up to its title. Every shot is a marvel of photography, whether through choice of color, composition, or use of light. The sun cascades through an open window, backlighting our hero as he considers writing again for the first time. The frame roves restlessly through rooms and parties, tracking behind children playing in an ancient garden, lie-affirming in its controlled movement and energy. The beauty of the female body seems less exploited than celebrated; the same for the crumbling, dirty metropolis known as Rome. Sorrentino doesn't hide the fact that the city is falling apart, but finds beauty in the textures of passing time. The opening party scene is an editing marvel: figures gyrate under strobes of neon, and the images are arranged in sequence that proves hypnotic, combining the fast and the slow, quick glances of faces and gestures leaving an impression long after they've gone. Then there is the music, an expansive compilation of existing works, from Italian pop to Kronos Quartet to Arvo Part. It feels like a tapestry of all the many details of life- not unlike the film as a whole. Sorrentino seems to be seeking to show not a slice of modern life, but aiming for the impossible task of suggesting all of it, as seen through the lens of an older man whose studied perception is just as vibrant as anyone else's- perhaps moreso, because of the nigh-Taoist calm with which he sees it all. This picture is a sensual overload, and it closes on a note of quiet joy utterly unique to itself. Far and away the film of the year. 2. To The Wonder (Malick) A Parisian woman (Olga Kurylenko) moves to Oklahoma, struggling to find happiness while married to her husband (Ben Affleck). A local priest (Javier Bardem) struggles with his faith. Trailer. In the heady days when auteur theory was first burgeoning forth, courtesy of Andrew Sarris, Truffaut, and others, it was a taken a s point of pride and skill when a director could assert his authorial voice in his films such that you could instantly identify who its maker was. This concept still holds largely true, and I for one believe there's no better definition for a great director. Howard Hawks said it best when Peter Bogdonavich once asked him whhat great direction was: "when you can tell who the devil made it." When you put on any film by Scorsese, Fellini, Welles, Mann, Antonioni- it doesn't take more than a few minutes to tell who the director is. The confident and dexterous clarity of voice these greats and others possess is, in my mind, the indicator of a great director by the same measure in wchich we evaluate great authors and composers. Not everyone loves Malick, but everyone will agree that his films are instantly identifiable. His latest is by far his most divisive, but I think it's one of his best. To The Wonder follows a woman's (Kurylenko) relationship with her husband (Affleck) and a priest's (Javier Bardem) relationship to God. Both are searching for- what? happiness, self-realization, peace. Deep, inner satisfaction. The film assumes your understanding of the basic plot and chooses to go deeper, dispensing with story and exploring instead the textures of this search. The approach feels both broadly sketched and startlingly intimate (especially in its use of voiceover) at the same time. Definitely the most abstract of Malick's already fairly abstract work, the content of To The Wonder is told mostly through its elliptically sequenced images. Affleck told audiences at Telluride that the film "makes Tree of Life look like Transformers," and indeed, it's a challenging film- but only if you're expecting a normal movie. I say let the images wash over you. The joy of the camera, swinging through the trees in Paris, making tangible the energy of early love; the mystery of the last two shots, which when paired together evoke a loss, but also the calmness of having been found; whispered nothings on the soundtrack, ruminations of lonely people, as they walk around in the corners of the widescreen frame. Don't try to decode everything- let the ideas and sensations work their way into you, right-brain style, of their own accord. Things will click together on your drive home, or a day later. Suffice it to say that if you're feeling adventurous, and are someone who finds yourself ruminating often on whether or not love is connected to self-realization, or the existence of God, the frustration of not knowing people who are close to you, or breaking free from doubt... you'll find this film of interest. Certainly there is no more rapturously beautiful film to come out this year- wherever Malick turns his artful gaze, our perspective is transformed by his. Sight & Sound critic Nick Pinkerton writes on the subject better than I can: "Malick is one of few filmmakers who could, in the space of a few images, go from Mont Saint-Michel in Normandy to a fast-food drive-through in Oklahoma without implying a pejorative judgement about either, dismissing the Old World for the New or vice versa. At one point, Bardem’s priest preaches about the necessary will behind a husband’s conjugal love – “He does not find [his wife] lovely, he makes her lovely” – and Malick similarly does not film things because they are beautiful; they become beautiful because he films them." Malick, a former Oxford Philosophy professor (he translated Heidegger's Essence of Reasons into English), invests his films with a wisdom of observation that makes the act of watching his films feel valuable- but never in a preachy way, as most of the meat of the picture is not explicit, but implicit in imagery and music. Pinkerton's full review is one of the best pieces on the film; also insightful is Roger Ebert's- this was the last film Ebert reviewed before dying. Both men offer similar appraisals on the film while coming from very different places, and address some of the concerns brought up by other viewers. Not a film everyone will take to, but one I can't get enough of. 3. 12 Years a Slave (McQueen) True story of a free black American who was captured and enslaved for twelve years before escaping. Trailer. There isn't much to say about Slave that hasn't already been eloquently discussed elsewhere. Steve McQueen's new film is among the more powerful cinematic experiences I've seen in my life. It remains 2013's best-reviewed film, and I find the verdict of the critical community impossible to disagree with. I'll restrict my comments to those I feel are underrepresented in the discussion: To open the pages of Solomon Northup's book is to be teleported instantly back in time. His memoir of his horrific experiences cuts across the intervening century with unexpected force, and the film, which sources the book heavily, possesses an authenticity I have not encountered in other films about the period. To have this document, written by a highly educated black man who lived through the events, is something approaching a national treasure. It reveals how much artifice there is in other supposedly historically accurate slavery films. We know from evidence how much differently language was used in the 1940s as compared to films made in the 1940s; here, we see characters who speak in ways we've never heard in the movies before. The articulateness, the cadence and rhythm- all derive from Solomon's firsthand experience, and as such illuminate the world in ways that startle in their clarity. Mr. McQueen's images are muted in their style as compared to his normal approach, but they are still visually compelling. Some reviewers have taken him to task for this, calling the film "too beautiful," but I have to go to sleep when I hear such arguments: using natural lighting in the American south is unavoidably going to give you vivid images. Part of the horror of the film is how such atrocities could occur in such a natural paradise. The distinctly southern landscape shots of the willow trees, sunsets and bayous contrast the horror, and in their containment of slavery help us see the land into how Solomon must've felt when in them: unremittingly ugly, and symbolic of cruelty. As for McQueen's sophisticated use of chiaroscuro lighting and visually dynamic compositions, he is not aestheticizing the content, so much as doing his simply job as director- maximizing the potential of the image to be a device for communicating information to the audience. For example, note the infamous flogging scene. Patsey, Lupita Nyong'o's character, cannot turn away from the torture inflicted on her; and so neither can we, because McQueen does not cut away at all during the scene, which is filmed in a single unbroken take. Her pain is relentless and without pause, and so then is the language of the camera, not breaking up the scene with edits, using pans instead (it's the only scene in the film with handheld pans). This isn't style overwhelming substance; it's style in the service of substance, making for a more unified and compelling experience. There is absolutely no reason why a film about human tragedy, or any other subject, for that matter, should be visually placid. Critics who take McQueen to task on this issue are ignoring the inescapable fact of the inherent beauty and texture of the American south, as well as misunderstanding the director's responsibility as truth-teller and skilled visual communicator. They ought to be ashamed of themselves, in other words! Among cinema's most valid reason for existing is its ability to engender empathy. Few other art forms are as potent in their capacity for getting us to experience the world through another person's shoes. Not everyone possesses this skill, and I think it's invaluable for being a useful member of the world community. There is still tremendous anger and unresolved frustration over slavery, the great and enduring embarrassment of our country. Although this is not an American film, I feel it only fitting that this be required viewing for every American; let it be shown in all the schools, that our children might more clearly understand the conditions of life their ancestors were forced to call commonplace. Slave is the first film about American slavery told from the perspective of a slave. Its journey and insights are deeply and cogently valuable to comprehending the human condition. Perhaps not the best, nor certainly my favorite, but definitely the most moving film I've seen in years. The rest of the list: 4. Gravity 5. The Past 6. The Wolf of Wall Street 6. Prisoners 7. Her 7. Fruitvale Station 8. American Hustle 9. Before Midnight 10. Dallas Buyers Club 11. Captain Phillips 12. Mud 13. Inside Llewyn Davis 14. Blue is the Warmest Color 999.99. Nebraska

0 Comments

It's more exciting than a show- it's a tour!

You're invited to Seattle Art Museum's First Thursday for a FREE 30 minute tour of highlights from SAM's collection, as you've never seen them before- given by yours truly. It'll be an irreverent but loving celebration of SAM's overlooked works. Have you missed my artist talks in the past? Here's a video of the speech pictured above, if you haven't seen it already (that one's actually about buses!). Take a quick detour on your Thursday (March 6th) night plans, and join me from 6:30 to 7 for a tour unlike any given at SAM before! Details and location here. Hope to see you soon! At 3rd and Virginia, on my 358: a large African-American man in his fifties gets on. I ask him how he's doing. He's doing fine, and he sits down somewhere behind me. A moment later he comes back up.

"Hey, what's your bus number?" "Wha-?" I don't know what the coach number is myself. I glance up at the front wall, saying, "it's 2618..." "Oh no, no!" "Oh! It's a 358!" "Tight. Thank you!" "I was worried for a second there. Thought I was doin' something wrong!" I had thought he wanted my number so he could file a complaint! "Oh no man, you cool!" We're both laughing now. "I was like, I thought I was doing everything right..." "It ain' like that! You doin' a great job." After a moment I ask about his holiday, because what reason is there not to. Together we find new things to share about the weather, the holiday traffic, making it to the end of the week.... Sometimes I wonder if people find it off-putting when I strike up conversation, but I'm surprised at how often- and how willing- people are to open up. You just have to ask. I wanted to offer a Scott Adams quote which a regular reader was nice enough to share with me: Remember there's no such thing as a small act of kindness. Every act creates a ripple with no logical end. "It's gonna be a good year," he says, surfing the wave of our interaction, before disappearing into the melee known as Third and Pike, center of the universe. This is the second-to-last installment of my list of unabashedly opinionated top ten films of the year. By "ten" I mean fifteen- don't listen to the naysayers. It's been a great year for film. Hope you enjoy the analyses!

For reference, here's Part One of the list, Part Two, and Part Three. 4. Gravity (Cuaron) A medical engineer and an astronaut work together to survive after an accident leaves them adrift in space. Trailer. My review, posted on this site in October, is available here. 5. Le Passe (The Past) (dir. Farhadi) A woman in the process of finalizing a divorce, her husband, her children and her new boyfriend wrestle with pasts that link them all. Trailer. What I want to impress is how thrillingly engaging Farhadi's films are. Don't pass this one up because the synopsis sounds heavy or serious. The new Jason Segel comedy can wait. There's no one else out there making films as Farhadi does: domestic dramas structured as thrillers, with information and character revealed in layers, keeping us at the edge of our seat. Like a thriller, we can't tear our eyes away, because we feel for these characters as new revelations come to light. In terms of urgency, his films go one better than genre thrillers- we're tense not because the information is about a fictional good guy looking for a fictional killer, but rather about humans like ourselves, going through struggles we find intensely relatable, because we are not detectives or serial killers after all, but ordinary people, human beings who deeply and innately understand the crises portrayed onscreen. We sympathize with the characters as we do our friends, because the protagonists have been developed so fully. Why resort to such prosaic devices as villains and plots when there is so much of real life to explore? Among cinema's best virtues is its potent ability to situate us in the life experience of someone else. Films help us empathize, and it's easiest to do so when the characters are as rounded and dimensional as the people we know in life. Such is the case here. Farhadi's previous film, A Separation, and his latest are both about couples in the process of separating, but they go about that subject in very different ways. Both films end up being about dramatically more than that single subject, complex though it already is. A Separation deals with the frustration of leaving your homeland because of what it's become, while focusing on the many sides of filial, cultural, and religious obligation. The wife in that film wishes for a divorce, that she might move outside Iran and offer a better life for her only daughter. The husband in The Past, on the other hand, has already abandoned his wife and her children in France, to return to his homeland of Iran. The characters in A Separation were on the brink of making big decisions; in The Past, the life-altering choices have already been made, and they must now deal with the messy aftermath. Robert Altman once said, "people tell me all the time that they have seen my films, what they really mean is that they have seen them once." In the spirit of that quote, I must admit that I've seen these two pictures only once each, and that is not nearly enough to take in the complexities of all that is explored in each piece. A reader can easily imagine the many facets and directions the above scenarios contain; Farhadi dives into them with thoughtful rigor, directing all his energies to fully realizing the complexities of the contemporary condition. These two pictures remind us what actual life is like, and in their quality make so many other films seem stilted by comparison. I will leave discussion of the film's substance to those better qualified. On a single viewing it feels too rich, too large to wrap my hands around. It carries with it the pleasant satisfaction of reading a novel you know you will have to revisit, because of its great depth and skill. With regards to content I will simply say that it contains multitudes. Bejo's performance is enough to move one to tears; Ali Mosaaffa disarms with his uncanny ability to appear effortlessly genuine; and Tahar Rahim once again stuns, nowhere else than in the film's last thirty seconds, which are as profoundly affecting as any scene I've seen this decade. What I do feel qualified to discuss, however, are Farhadi's aesthetic choices. He moves forward from A Separation's muted, naturalistic color palette to something more vivid here. Greens abound in the midtones, and blacks are deeper; colors are still naturalistic, but they are allowed to bloom in ways they didn't before. Farhadi and regular collaborator Mahmoud Kalari position the camera as objective observer. Though most scenes are told from the perspective of a specific character, the camera doesn't always emphasize this, preferring to stay neutral in the battleground of family tensions. In like fashion, Farhadi avoids using any music until the end of the film, exactly as he did with A Separation. His choices seem to be all about minimizing artifice, and letting the content speak for itself; he aims thus for an aesthetic that isn't flashy, but not banal either. The measured, precise editing and carefully considered mise-en-scene are too good to call this an actor-centric piece. Compositions emphasize observations of performance- unspoken thoughts on characters' faces, reactions during dialogue spoken by others. Natural light is used more heavily in The Past, to great effect. Farhadi continues his preoccupation with reflections, and there is a terrific steadicam tracking shot following Rahim off a train, onto a platform, out of the platform area and back into it as he searches for his son. At the end of the day, though, this isn't a film strong on style. It astounds by virtue of the content's overwhelming ability to compel, and through its quietly devastating and carefully considered realities. There is great wisdom in the observations made in this picture. 6. The Wolf of Wall Street (Scorsese) A look at the lifestyle of mid-90s stockbroker Jordan Belfort, from his perspective. Based on Belfort's Memoir. Trailer. "...[T]here are more and more billionaires popping up every day, and you often wonder, 'Okay, what is their contribution to the world?' When are we going to take that crossroads where they actually have a concern for anyone except themselves? ... Because, to me, this attitude of what these characters represent in this film are ultimately everything that's wrong with the world we live in." -Leonardo DiCaprio Okay. There's a lot I want to get off my chest about this one. Here goes: When the dust settles, Martin Scorsese's Wolf will be remembered as the film of our time. The other films on this list may be more immediately satisfying or obviously brilliant, but Wolf challenges us with uncomfortable truths, and lays bare a hypocrisy most would wish to turn away from. The villain of the piece is not the protagonist, but the individuals in the last shot (which is discussed here)- a society that doesn't just choose to allow such monsters to exist, but who also wish to follow in their stead. The great horror of Wolf is that its entertainment and comedy are not at odds with its social indictment. Scorsese's masterstroke here is what he chooses to leave out. From the opening moments, we're aware of a complete lack of any moral center. No mention of this absence is made, but as the film goes on, we're bombarded with a sensory overload of everything but that, and the longer this behemoth of a picture continues, the more conspicuous that absence is, until finally it's the only thing we're thinking about. When, near the film's end, Belfort for the first time performs an action for someone other than him, the action is jarring and noticeable (and, ironically, what ends up landing him in custody). Scorsese has said that it would be too comforting to impose morality or judgment on the characters inside the film; doing so would suggest that the problem has been solved. It hasn't. It's up to the audience to awaken and impose those perceptions in life. This is a film about characters too far gone to understand the consequences or context of their actions. In this manner, the conference in which Belfort and co. discuss the what's appropriate to do to hired midgets at a work party functions as the film's whole in a capsule: the characters are unaware of the absurdity of how they're thinking. Wolf is told from the perspective of the characters themselves, and as such it has no place to objectively comment on its portrayals. It's up to us to perceive that. Scorsese expects us to be intelligent. I would hope that any audience would be sharp enough to not have to be told how to evaluate the moral content of the stockbrokers' actions. Is it so important to judge? We can go further by trying to understand the headspace these characters live in, the contempt people in money culture have for others, and more firmly decide where we stand. Those familiar with Scorsese's ouvre knows of his fascination with the downtrodden, the marginalized, the unscrupulous- what the rest of the world calls "bad guys." He casts his disciplined eye on these nefarious types with compassion. One of the great hallmarks of Scorsese is that his characters, like real human beings, do not experience radical transformations or grand character arcs. Like most people, his characters don't change. At the films' conclusions, they've hardly learned anything- but we certainly have, watching them and their behavior. Wolf takes this approach to a nigh-unwatchable extreme. There is no character in his filmography more selfish, or with less scruples. Wolf is the work of someone deeply dissatisfied with society, and who has something to say about it with urgency. I don't wish to dwell too much on the manufactured "controversy" over the film; the picture speaks for itself. Most of the rumblings seem to be coming from those unfamiliar with Scorsese's approach to character, but even without that it should be a logical conclusion that a film about mysogynists needs to show mysogny. There's a difference between depicting an action and endorsing it. We are confronted with an attitude that is very wrong, and the lack of commentary or closure within the text of the film induces us all the more to take action, or at least reconsider our perspective, in life. We have to provide the closure. Some cinema historians posit that in the history of film, portrayals of strong, independent women in film happen most often during eras of great gender inequality, and as conditions for women have improved, depictions of them in film have gotten lazier. There are enough examples that fit this trajectory to lend it some credence (ask any serious female actor which decades had the best roles!). However, there are numerous exceptions to this general trend, and Wolf is among them. Who looks bad at the end of the picture? Unlike the men, who combust under the film's withering gaze, most of the female characters get away clean. They are not mere enablers, or defined only by their relationship to men- you'd be surprised how many films do exactly this, without going much further. Belfort's two wives are individuals who think for themselves, and use their own (very different) ways to keep the marriage afloat and ultimately take care of themselves. Scorsese seems interested by this dynamic: this is his third film about long, troubled marriages ruined by character flaws that were there all along. At the end of the day, there are only three moral anchors in the picture: Belfort's first wife in the film's first act, Belfort's father (Rob Reiner) in the second act, and Kyle Chandler's FBI agent in the third. It is Chandler who gets the last laugh riding home on the F train, defiantly unswayed by Belfort's tempting life, "worth more than the whole damn bunch put together," to quote a similarly-themed work. Rob Reiner is the lone voice of reason. Like Tom Wolfe's I am Charlotte Simmons, another story about characters who lose their souls without realizing it, the authorial moral stance on the film's characters is verbalized only once. As mentioned earlier, Mr. Scorsese expects us to be paying close attention. We have to supply the missing puzzle pieces. No one's talking about the craftwork in this picture right now, probably because of how volatile the subject matter is. I can't help but put in a good word for Marty's below-the-line talent, however, which helps the film be the masterpiece that it is. Most controversial films (I'm excluding horror here) also happen to be incredibly well-made; if they weren't, well, they wouldn't be controversial. They'd just be bad. A Clockwork Orange, Natural Born Killers, The Wild Bunch, The Public Enemy, Last Temptation of Christ, Night of the Hunter, Blue Velvet, Antichrist, Birth of a Nation... don't tell me any one of these aren't astonishing aesthetic and technical achievements. Wolf is no different on that front. As usual, Thelma Schoonmaker's editing is aces, and the long months she and Marty put into every one of their films together always shows onscreen. Here, they take a different rhythm than their typical accelerated, high-density approach. While the pace is still rapid, shots roll for longer, to accommodate the improvisatorial mode of acting Scorsese and his actors opted for here. Shots last onscreen for no longer than they take to communicate the information their intended to offer, as per Scorsese's normal M.O., but many dialogue scenes are accomplished with less angles and simpler setups, allowing the improvisations to be captured. Nevertheless, there are still plenty of highly designed shot sequences, and Scorsese and Schoonmaker continue their habit of dispensing with the beginnings and ends of scenes in the final film. The film may be three hours, but it feels like four hours squeezed into three (and it is, interestingly; read this in-depth interview with Schoonmaker for lots more on the film and their working relationship). Working with Scorsese for the first time is Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu's (Babel) regular cinematographer, Rodrigo Prieto, best identified by his high-grain images and love of rich, filmic colors. Though Scorsese had intended to shoot the film digitally, he and Prieto opted for film instead because of its superior ability to capture skin tones and general color nuance. Digital was reserved for low-light situations. Early scenes in Wolf are deliberately flatter and reduced in depth of field, to suggest Belfort's lack of confidence and direction in those moments. Later on prime lenses are used and diffusion filters removed for more pristine clarity, and colors become more defined. Prieto pushes the negative a stop in some scenes for greater grain and contrast. Elsewhere he uses daylight film stock under tungsten-balanced flourescents for an amber hue. When Belfort hits his stride in a big way, working in massive offices and commanding entire floors of stockbroker minions, Scorsese opts for "wide focal lengths, deep focus, white light, vibrant contrast and quick, defined camera moves.” Certain shots in the quaalude sequences were shot at 12fps and double-printed for a slow-shutter look. These visual pyrotechnics are a pleasure to behold for photographers and non-photographers alike. One gets the sense of a carefully designed work, where all the tools of the craft are being harnessed to being communicate a lot of information. Rather than relying entirely on dialogue, Wolf, like so many other great films, maximizes the potential of the medium to overload us with information. There is so much thought put into the frame- the decision for the camera angle and composition, the aesthetic qualities of the image, the mise-en-scene, the performances (I'd write about how this is DiCaprio's best performance in an already great career, but I think that goes without saying), the music... watching great films sometimes reminds me of driving the bus. Both are a complete deluge of data, to be processed and considered, and enjoyed. It's that kid again, the one with the observant eyes. I've had a chance or two to chat with him in the interim. He is Amad, dressed in ordinary, low-profile garb for someone his age. No flashy bling or starched denim- just a regular dark gray hoodie, not baggy, and jeans that fit. He's coming home from school- it's late afternoon on the 4, several hours after the schools have let out. Absent-mindedly I wonder what he was doing hanging around for so long before going home.

"Hope it was a good day at school," I say. I like to engage the young folk, to give them the example that yes, strangers can and do talk to each other. As a youngster, such opportunities can be strangely absent, particularly if you're not employed; you may spend years of adolescence talking only to peers and adults in environments you already know. "It was alright," he responds. "Kinda late to be gettin' outta school." "Yeah. I stayed late to get my homework done." "Oh, right on." My mind was in Parent Mode, automatically worrying he was up to no good. "That's a good idea. Get it out the way." "Yeah, then I can jus' go home, don't have to worry about it." "Don't have to worry about it, exactly. And it makes more sense, do school when you're at school, then go home forget about it. Like keepin' home life and work life separate." "Plus it keeps me from procastinatin.' And it's easier to think about school when I'm there." He's young, eleven or twelve tops, but his mellow and open demeanor suggests an intelligent humility in which you almost feel outmatched. I like feeling outmatched. It means I can learn something. "And then maybe you don't have to carry all them heavy textbooks around," I'm saying. "Oh we don't carry no textbooks anymore." This is news to me. I'm incredulous. "Hang on. What?" "Yeah, it's all digital now. You download it at the start o' the semester. Put it on your iPhone. They give us all iPads to use during class." "I don't believe it. They give people iPads? Man, I musta carried twenty pounds a textbooks every day..." I suppose I sound like my Grandmother once did, when she told me how she rode a wagon every morning to school. Amad and I marvel at each other, sharing amazement. They don't even turn in papers anymore, he continued. You just email your teacher. Compared to my experience it seems like unadulterated decadence...and a continuation of generational disconnects going all the way back to- well, you can imagine a Australopithicene father complaining to his son about everything he had to do before there were stone tools. To myself I wonder, what's normal to Amad? What will he tell his children? That he had to lug around those clunky iPhones every day, which weighed almost five backbreaking ounces? "I wonder about cars and driving in future," I say. "Man, the way things are going soon people won't even walk." "Oh! Don't say it!" "Man, in twenty years this job won't even exist." "Oh, that hurts!" He's smiling. "I'm a miss it though. I love it so much." "Yeah, but you'll still need a bus driver for, for the, uh," "Interaction?" "Yeah! That's the word I was gonna use. Interaction." "I sure hope so," "'Cause people be wantin' the customer service," "The back and forth between real people," "Yeah, uh mean, you gotta have that." "Man, I am happy to hear you say that. It is important." It was clear he thought this was a crucial component of life. What was normal to him, I imagined, must be a world in which information and communications technology reigns supreme, a part of every action in life and a wonderful time-saving, streamlining- and alienating- buffer for all everyday activity. I was not quite correct. Somehow, this boy understood that despite the wall-to-wall technological barrage he's growing up in, there is something undeniable about tactile, direct human interaction. The elemental straightforwardness of it. We humans possess a profound yearning to reach out and touch each other. The buried desires, dreams of validity and self-realization touched by the sound of a voice facing you, by the awakening glance of eye contact. Somehow it feels natural to keep that flickering flame alive. This post also available on The Urbanist.

This piece is a follow-up of sorts to two writeups from last year, "(Hopefully Not) The Last Day I Drove the 358," Parts One and Two. Her black baseball hat has some sort of lettering on it, black calligraphy on a black background. She tosses in the correct amount of coins for youth fare, shoulder-length curls framing clean olive skin and tastefully dark make-up. "What does your hat say?" "Actually, it says cunt." "Oh. Awesome," I responded. "Bein' bold!" Why did I say her cunt hat was awesome? Because a silent response would carry a meaning that wouldn't be true. Silence would too easily be misconstrued as judgment. She's trying to stretch the muscles of her identity, searching for herself in the far corners of adolescent expression, and in that respect her boldness is an inquiry to be commended. I'm excited for when she settles a little, relaxing into her being, able to calmly touch the shapes of who she is. She's taking part in the great search, and that is awesome. I'm on my last trip of the last day of the 358, and I'm having a blast. Earlier there was a runner, moving slowly, hurrying as best he could toward my first outbound stop at Second and Main. How could I refuse anyone on the last day? I'm Don Corleone, and it's my daughter's wedding. The runner turned out to be someone I knew- Ken, a shorter African-American gent in his forties, always with a ready smile. He's general manager of a restaurant in Pioneer Square, and they're in the process of renovating the building. We make the turns gently on Main and Prefontaine, and he's telling me about an unfortunate hospital incident which led to his temporary inability to run for the bus. He's still smiling though, busy as ever, and seems excited to find a seat and relax into the cocoon of a nice, long ride home. I take it slow up Third. I want to get overloaded today. "Hope you have a lot of tissues for everyone," says an older gentleman boarding at Union. "I know! I'm about to burst into tears myself!" At Denny a woman in her twenties gets on. She seems uncharacteristically haggard, but excited by my attitude. I ebulliently announce the upcoming changes ("Starting tomorrow this'll be called the E Line. E is for excellent."), and we're on our way up Aurora, merging with the afternoon madness of Friday traffic. I step outside the bus briefly to make sure that man over there, slumped over on the stack of tires, isn't dead. He's been there several hours. A woman deboarding at this stop stays around to check up on him, without giving it a second thought. I marvel at the global sense of family out here. Later, at 46th, another older gentleman looks at me, accosting me with: "Okay. This isn't gonna work. I'll be needing to see some I.D." "You found me out!" "Don't tell me you're of legal driving age." "Definitely not. I have a ways to go." "Well, you've got the edge, being young," he says seriously. "Me? Nooo! You've got the wisdom, right?" "Well, the trouble with having the wisdom is, nobody listens to you. I got four kids, and they don't hear a word I say." "That's their loss," I respond. "Instead of listening to you they'll have to make a bunch of mistakes to get to the same conclusion." Inwardly I'm thinking, as true as that may be, it's unavoidable. In a way, we need this problematic aspect of existence. Our emotions and experiences feel new to us, though they've been undertaken by untold billions of others; love, joy, and pain are older than time, but they feel real when they happen to us. Would we really want it any other way? "Exactly," he said, in response to what I'd said aloud. I didn't feel the need to voice my thoughts. "How old are your kids?" "What? Oh. They're forty-one, forty, forty-two. Forty-four." "Okay. I'm sure you're proud of them." "Oh, yeah." "I wonder about that sometimes. Having kids. Often I'm not sure that I want to." We've never met, but somehow it feels natural to quickly shift gears into a meaningful, personal discussion. Sometimes that's possible with intimate family- and, curiously, with strangers. He's telling me his fears of the dangers the world contains today, and I'm telling him how ill prepared I feel to tell others how to live, when I'm still struggling to work that out for myself. I want to tell him the world has always been a dangerous place, but we deal with it. Someone else chimes in, telling me we're always trying to figure things out, figuring out how to exist. But we deal with it. We're considering the angles, finding ways to agree with each other, and then a mob gets on and our older friend retreats with the incoming tide. It's a continual game of shifting gears. I find it exhilarating- each of these unique lives, with a contrasting set of concerns, each of us in a different space in life. A close friend recently told me no matter what sort of attitude a person confronts us with, we can realize we've experienced a similar frame of mind, or at least a similar root that could've led to comparable emotions. Through the stream of these wildly disparate parts of life I'm being confronted with, I realize we've all experienced similarities over the course of our lives. Three Big Brothas (not the Orwellian variety) come up from the back to address me. The leader is walking a touch slowly. "Listen boss." Bawss. "Hey!" "I was wondering I coul' ask you a favuh." "Sure thing." "I got to ask you fo'a courtesy stop jus' pass 117th. We got to check out this motel tha's right there." "Today only, my friend! I be happy to." "Man thank you. 'Cause I know after this you don't stop until," "125th," "125th, yeah." Then, quietly, he adds: "my hip is sprung." On hearing that my thoughts from a moment before are reinforced. This man doesn't know it, but Ken, the restaurant manager sitting a few rows back, is also having hip problems. That's why he wasn't able to run up to my bus as he normally can. "No worries, man. Happy I could help." "Ah appreciate choo." They go back to the back lounge, and I make the announcement: "okay folks, we're going to make an extra stop tonight, just to be nice, far side a 117th right here, 117th. I got to ask us to use front door only here, front door only, watch your step tonight..." Each of the three brothas thanks me from the heart. The last one, tall and skinny with corn rows, ducking his head to avoid hitting the ceiling, has in his eyes a gratefulness I only occasionally see even in people I know well. Maybe because he knows he may not see me again, the emotion is allowed to be an outpouring. I feel humbled; what a complete privilege it is to be here. There is the sensation of something tactile being built in such moments. Stewardship, global and real, budding in the dirty blue shadows. Everything starts somewhere. "Tha' guy's hella cool," I hear somebody muttering outside as I close the doors. The uncharacteristically haggard young lady from Denny comes forward. I say uncharacteristically, though I see her only rarely, because her sad look appears out of place on a face built for smiling. Periodically I had glanced in the mirror, noticing her taking in the ride. I ask, "how was your day today?" "Oh, it was okay." "Like a seven out of ten, maybe?" "Wha-?" "Or six out of ten? You know, grading it on a scale-" "Oh yeah, like maybe a seven." "Seven can be good." "I guess." "That's a C. That's a passing grade." "It's passing," she says, smiling. "Yeah, seven can be pretty awesome. Are you ready for the weekend?" "Oh my goodness, definitely." "You and me both! There we go," I say, pulling up to the stop. "Treat yourself to something nice tonight." "I will." She seems rejuvenated by the idea. "Thank you!" Ken himself comes up at 145th. Before he's even at the front I'm already talking to him: "Restaurant mus' be busy tonight! Valentine's!" We get back to the renovations he'd been discussing. I've been to his establishment before, and can picture the layout. "How's all that goin'?" "Slow, man, slow." "I remember you said there was all kinds a red tape, 'cause it's- is it a Historical?" "Yup, it's classified as a Historical (building). But lemme tell you, when we took out the floor of the stage and seen what was underneath, I couldn't believe those last couple a bands didn't bust through the floor!" "It was that bad!" "Oh, the amount of wood that was rotting, everything falling apart," "You're a pro though! I know you're gonna make it look beautiful!" "Thanks. Hey, I'ma get off at Walgreens here tonight, go look for something for the wife." "Lookin' for somethin' pink, right?" We cackle with laughter and do a great big handshake. "Happy Valentine's day!" "You too, happy Valentine's day!" At the end of it all the cunt hat girl steps out, the last passenger of the evening. The bus's signage changes automatically to "North Base," having displayed "358 to Aurora Village" for the very last time. "Have a really good night," I say to her in a meaningful tone. "Thanks! You too!" It felt important to me to get that last exchange out. I wanted her to know there are people who don't look down on her, and that I certainly wasn't judging her for her 358-appropriate hat. It's a frame of mind we can all relate to. I'm honored and thrilled to now be part of The Urbanist, a site dedicated to examining urban policy and expand our thinking on public transportation and numerous related subjects.

Some time ago I posted a massive post detailing what a day on the 7 is like. As the 358 winds down to a permanent close, it's time for some similarly massive thoughts on Seattle's most notorious route. -- I was at Central Base once when I overheard two other operators talking about me. "This guy only drives the 3 and the 4. And guess what, last shakeup- he drove the 358. For fun!" "What?" "Yeah. He's insane. He went all the way to North Base to pick the 358... On purpose!" Why did I choose to pick what some call "The Disease Wagon" again? Why was I so adamant about snagging "Jerry Springer" one last time before its deletion, to the point that I took a hour and a half cut in pay simply to get my grubby hands on it? The obvious answer is because I love the route... but why? By way of more clearly describing what the route is, I offer a few excerpts from the route's Yelp page. The fact that it even has a Yelp page (not to mention songs based on it, and celebrations and condemnations in numerous publications) gives you a notion of the route's continued cultural presence. I can't help but share some excerpted alternative opinions:

We even have a 358 haiku, offered by Jonathan S.:

Honestly - who reeks?!" In counter to these memories, I offer an ode published in Seattle Weekly, when it was named best bus route in 2013:

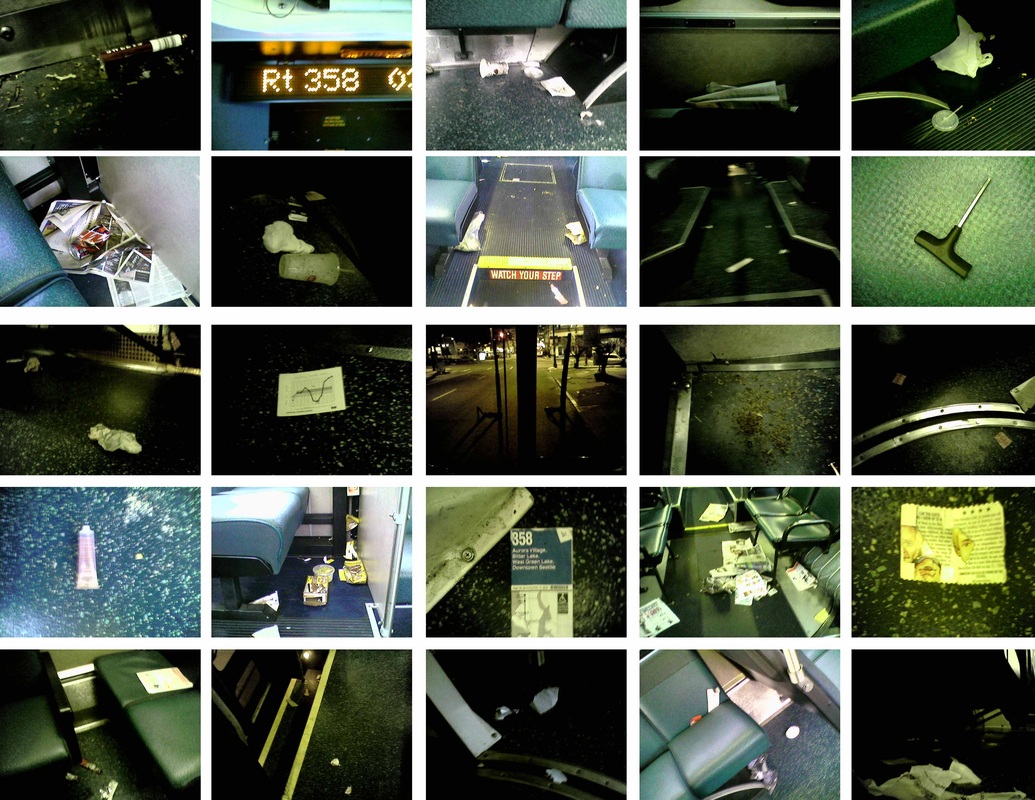

A 8 x 10 blow-up of the above is hung on the wall at North Base. Some drivers are planning a party at North to celebrate the route's demise and welcome a new era wherein they'll never have to deal with the route again. In the same breath, a number of operators are planning to ride the last 358 trip, to glory in the last hurrah of a cultural institution that will breath its last breath in the waning hours of this coming Valentine's Day. You can guess which group I'm in! Nowhere else will you encounter such a group of souls as those I have the pleasure of spending time with on this route. Yes, they swagger on with all manner of questionable and dangerous items peeking out from under their jackets. They hobble around with stuffed garbage bags and needles. Beer cans and condom wrappers share space on the floor, along with strange powders, leaves and pills that defy my understanding. Once, on the same bus, I found a collection of the following: bras, surgical masks, gummy worms, and board games! Materials for quite the weekend in Vegas! You don't just see increased police activity here; Aurora Avenue is where police cars drive past each other in opposite directions because they're going to separate incidents. The people are cloaked in smells I've never experienced and can't begin to describe. I helped a woman with directions, and as she assaulted me with her astounding breath I was more bewildered than displeased, as in: how did this train wreck of a fragrance come into being? How many ingredients and lab experiments would it take to replicate it? Before I started this job, I had a tendency to romanticize the poor. I read Tolstoy and liked Millet and Henry Tanner. Van Gogh wrote of the truth he saw in peasants' eyes, and how he found it nowhere else. Being familiar with these works, and coming from the working-class background that I do, I had certain inklings about the poor I believed to be true. After driving bus for several months, and being in daily, close contact with the lower class, I began to realize there were more sides to the story, that some people behave terribly, and as many make crippling life decisions as are simply wronged by bad fortune. I wondered whether I had been superficially romanticizing, when in fact what was actually going on out here was really just a bunch of...no. I had an epiphany. My epiphany, which hit me after driving the bus a few years more, was that my original inkling was in fact true. These are among the best people I know. When those damaged, craggy, beautiful faces get off my bus and say "God bless you," let me tell you, they mean it. People in Bellevue never say stuff like that. They don't treat me like this. My earlier realizations hadn't been overturned so much as reoriented, grounded and firmed up by the unblinking gaze of reality. Respect, gratitude, thankfulness, appreciation, empathy- these have incalculable currency out here on the street. I see disabled women getting up to make room for other disabled women. A "hello" from me goes further on Aurora and Rainier than it does elsewhere. It's a simple sound, but with the right tone it's enough to communicate the warm comfort of a judgment-free space. Often you can see what a welcome surprise it is- gestures of kindness are all the more impactful for having occurred in the supposed darker corners of life. "Thank you," a teen boy said in what was my last interaction of the night. He'd beseeched me for a free ride, and I'd given him one. I didn't ask why. Does it matter if his circumstances are his fault? He turned to me before stepping into the freezing cold. "It means a lot," he said, in a moment of uncool but beautiful honesty. I knew now by experience what Van Gogh was writing about. "Anyone who drives the 358 part-time doesn't know about the 358," a veteran report operator grumbled at me not too long ago. It was all he could do but tell me I had no right to be happy. Maybe he was tired of seeing my smiling face around the base. Comments like this amuse me. Anyone who thinks nothing happens on the 358 in the afternoons... well, let's just say that person really just needs to come out for a ride on my bus. Locals will tell you Aurora's drug transport and prostitution activities take place mostly during the daytime, when things are more easily accomplished using discount hourly motel rates and frequent bus service. More importantly, though, that grumptastic vet simply doesn't know where I'm coming from. He probably doesn't ride the 358 and a host of other routes at all hours on all days, and he certainly doesn't know that I do.* Beyond that, he knows nothing of my background. I was speaking with another operator years ago about why it was she and I both liked driving "the rough routes" so much, and the only commonality we could find among ourselves was that we were both from South Central LA. There are things I've experienced- without the authority and recourse to safety that being a bus driver provides- whose sandblasting negativity have absolutely no place on this blog. For me, they function only as healthy reminders that when something as marginal as a man defecating in his pants happens on my bus, I can recognize that it's not a problem. It's an issue. When boys are fighting in the back, it's an issue, but we get through it. I ask them to continue their fight outside, and they do so. "Hey, Nathan, I have a question for ya," driver Ted asked me once. We were both doing 358s at the time. "Sure, what's up?" "Well, I always see you driving that 358 smiling, all the time, every single time you're smilin.' How d'you do it? We're driving at the same time, we've got all the same people, and they're cussing me out, they're peeing in the back, I'm gettin' the works. How do you do it, man?" It's amazing what a difference tone makes. When you ask somebody how their day is, they generally keep their pants zipped. Ninety-nine percent of my day is in my control. In my recent post regarding Carlos, I write that his new construction job and resulting station in life has no catch. Is that really true? We could probably find one if we really wanted to. Maybe he has to take three buses to work instead of two, or he gets paid monthly instead of biweekly. The fact is, I think Carlos is happy because he doesn't think like that. If the catch is negligible, why bother contemplating it? I could choose to think my route is plagued with problems, or I could just embrace it all and get on with the business of being myself. Standing there at the base listening to the aforementioned grumpster tell me I knew nothing about the 358, I thought about calling him out and gleefully tearing apart his argument. I knew exactly how to do so... but I discovered I couldn't. I lack the necessary apathy. The fact is, I sort of like the poor guy. He may be the polar opposite of me in temperament, but he doesn't deserve a telling off. How would it help? One man's passion (love) is another man's passion (suffering), and nothing will change that. In conclusion, my love for the 358 can best be described by these two pieces- Ode to the 358, and Ode to Aurora. There is an undeniable elation I feel when I see a mob of street people at an approaching stop. It's a mystery to me. Any interpretation I come up with now would merely a supposition, and would fall short of a full explanation. I can only say I feel it in spades, and that, strangely, this feeling doesn't ever fade. *A suggestion for my newer bus driver friends: if you don't already, ride the bus. A lot. The best bus drivers are those who also ride the bus. There's no better way to learn about your job. In the same way reading all the time makes you a better writer, and acting makes you a better director of actors, riding the bus makes you much more aware of the type of experience you're giving to the passengers, and quickly shows you what works and what doesn't. You might find yourself surprised. Why on earth am I using decimal places in my list of films? Because it's been too good of a year! I just saw two more late releases from 2013, and I'd be lying if I didn't include them on this list! What was once a list of ten has ballooned into fifteen!

6.5. Prisoners (Villeneuve) A man's (Hugh Jackman) daughter and friend go missing. He enlists the help of a detective (Jake Gyllenhaal) to find them. Trailer. There is a tendency in film criticism- by professionals and amateurs alike- to confuse evaluation with taste. The criteria for evaluating a film has more to do with its craftwork achievements (acting, direction, below-the-line), and what the film intends to accomplish than whether or not it jives with our ethical and entertainment preferences. The next time you dislike a film, ask yourself: was it because the story structure was problematic, or the cinematography was lacklustre, or was it simply because the content was morally offensive or the material wasn't to your interest? In this respect, there are aspects of whether or not a film is well-made that are not a matter of opinion. There are swaths of gray areas, to be sure, but certain aspects of the filmmaking process can in large part be objectively evaluated. Thelma Schoonmaker's editing cannot be said to be "bad," even if it's not to our taste. We can hardly say that Ridley Scott's painterly directorial eye "sucks," to quote the common parlance; it is too proficient, too rooted in film history and painting theory to be termed incompetent. It's perfectly reasonable to dislike his visuals, but we can't get away with saying he's untalented. Prisoners is a film which pulls at this divide harshly. It possesses a brutality in its images and depiction of humanity that is crushingly difficult to stomach. Viewers of Villeneuve's previous work (the Oscar-winning Incendies, one of the best recent films and one of the most troubling) will have an idea of the level of diabolical intensity they are in for. Our theatre was filed with a chatty crowd during the previews, but once the film began, you could hear a flake of popcorn hit the ground. Villeneuve's command over his craft, particularly his camera choices and organization of scenes, overwhelmed a typically fickle audience into complete submission. The characters are developed so robustly- the film's two and a half-hour runtime allows for rich psychological detail- and the story events wound so tightly no one could turn away. That Villeneuve accomplishes this without resorting to shock tactics is an undeniable confirmation of his skills as a director, and the skills of his talented cast- Jackman's performance is a career-best. I will admit, however, that despite my tremendous appreciation of the film's skill, it is so disturbing I hesitated as to where to place it on this list. This is a work so powerful as to destroy one's belief in God, or shatter one's perception of a just universe. It makes you not want to have children. Film is among the most potent delivery devices for communication we have, if not the most, and Villeneuve and co. take full advantage. Roger Deakins' cinematography, with its slow movement and deep blues and blacks, enforces a level of dread rarely felt. The films has ideas and situations it wants to share with us, and it does so with stunning force. Your concept of the world may not be the same as some of the ideas espoused in this film, but they will doubtless get you to thinking, and that is the point of great art. This has been a year of finely-tuned, focused films of high intensity, and Prisoners is among the best. 7. Her (Jonze) Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix), a lonely writer, develops a relationship with an operating system designed for such. Trailer. There are lines in Spike Jonze's Her so cutting in their truth you want to write them on walls and consider them as mantras for living by. The plot allows for rich exploration of character and consideration of so many facets of love in the modern age- the pervasive effects of technology, its isolationist tendencies, the ramifications of loss and the hangdog persistence of memory. Most films about relationships are only about the beginnings of relationships. Her explores the full course of Twombly's relationship with sentient computer Samantha, as well as charting the emotional closure of his divorce with Catherine (Rooney Mara). Jonze seems to have an uncanny knack for knowing what the associated emotions feel like, and how to communicate them cinematically; the memories of Twombly's former wife surface at unexpected moments in the way that poignant memories do, and tell us all we need to know about how much she continues to dwell in Twombly's mind. We know all we need to know from the look on a face, and from this and so many other emotionally truthful moment sin the picture, there's no denying this is the work of somebody who's been there. Also notable is Amy Adams' performance in a key supporting role, the production design that suggests a near future without overwhelming us with it, and Hoyte van Hoytema's (Tinker Tailor) stunning cinematography. Deep rich blues and reds, a warm color scheme that maximizes the elegant and unusual production design, and a lot of shallow depth of field. Nearly every shot is onion-skin levels of focus. Like American Hustle, the images here are quite challenging to achieve. Hoyte's focus pullers must have been miserable, but their hard work pays off. A profound and eye-opening emotional experience. 7.5. Fruitvale Station (Coogler) A dramatization of the final 24 hours of Oscar Grant's life, the young man murdered by police on New Year's Day 2009. Trailer. Fruitvale stuns with its simple depiction of everyday life. Not unlike the first hour of United 93, another film in which routine actions are shown in great detail prior to a catastrophe, Fruitvale heightens the ordinary to a level of intense fascination. Most viewers will be familiar with how the day ended for Oscar Grant. Far from diminishing the film's dramatic value, this only increases the film's effectiveness. The banal and commonplace are heightened by a sensation of impending dread. Mistakes and urges toward goodness resonate all the stronger. Aside from its value in the telling of an outrage, director Coogler's film is valuable for its relation of all sides of a typical, contradiction-filled human being. He and actor Michael B. Jordan understand how we are all made of disparate parts, components of our personality with nothing to do with each other save that they all occur within ourselves- and that these seemingly contradicting sides are all equally authentic parts of us. In their hurry to sketch the essence of a character, many a film avoids such complexity. Even if the real-life incident had never happened, Fruitvale would still be a great film for offering such a nuanced portrait- particularly that of an exterior "type" we see so often, and project so much onto. There's much more to that young black boy in the back of the bus than what's piping out of his headphones. The film is naturally depressing for its unavoidable conclusion, but it's also oddly heartwarming in its deep-rooted belief in the goodness of people. Coogler, who also wrote, takes the time to show Grant's duality of self. He is neither good nor bad, but rather both, all together, all at once. Grant blasts gangsta rap in his car, then pauses it to chat with his mother. He's equally invested in both moments. His desire to give up selling drugs is as strong as his compulsion to do so, and we understand his thought processes on both fronts. He's raring to attack the man intimidating him in jail, and in the next breath crying over a dead dog, or asking his mother for a hug. The film gives its humans the benefit of doubt, as we should all do in life. Such an outlook fills me with positive energy, and makes me excited about humanity- and all the more disappointed in how the events transpired. In the end, looking at Oscar Grant's broken body on the platform, I couldn't help but think it hardly matters what sort of man he was. Nothing about his quality as a person can deny the egregious and unforgivable assault on humanity that was his death. There were so many chances for the incident to have never happened, but the inexorable passage of time can't be turned back. There was goodness in his soul, and there are those who think this was impossible. A flashback to my days as a film critic. Here's the first entry with an introduction explaining why there are film reviews on a blog about buses~

8. American Hustle (O'Russell) Four lives- a con artist, his lover, his wife, and an FBI agent- intertwine as all find themselves involved in the ABSCAM sting operation. With Christian Bale, Amy Adams, Bradley Cooper, Jennifer Lawrence, and Jeremy Renner. Trailer. American Hustle can hardly be called a movie, although it's certainly a smashing one. It's more like a wild animal, propulsively covering ground in a mad and disciplined rush, unfettered from the chains of mediocrity and prosaic formulas. I cannot overstate the heady rush of exhileration one experiences when watching David O'Russell's latest. You walks out of the theatre on that cinematic high you typically get in a Scorsese picture. I wrote last year of Affleck's resurrection as a serious writer-director; O'Russell's renaissance is no less interesting. While he has always been acknowledged as talented, his reputation as an infantile, stubborn tantrum-thrower tended to dominate the conversation before 2005. There was the very public falling out with George Clooney during Three Kings. We remember the alleged head-butt, and the handwritten open letter by Clooney, ever reasonable, as he defended the rights of crew who were being verbally abused on set. Topping that was the infamous moment- caught on video, or we wouldn't believe it- wherein O'Russell chews out Lily Tomlin in 2003 using what NY Times' Sharon Waxman calls "the crudest word(s) imaginable." Then there was Nailed, which shut down production in 2008 four times and was never finished, due to financial issues. While tantrums were not the cause for these problems, the chatter in the hallways of LA didn't hesitate to point fingers in O'Russell's direction, clucking with a lack of surprise: with him at the helm, did we expect anything else? At the time it was assumed O'Russell's career was over. Careers can end on one movie, and when the nail is hammered this many times, there's no ambiguity about it (witness former wunderkind M. Night Shyamalan's last five films, in which he dug himself deeper and deeper, each feature progressively worse in some way than the last). Extreme, drawn-out cases like this are unusual. Which is why O'Russell's resurrection- the overused term really is appropriate here- is all the more staggering. Six years after Huckabees, his last theatrical release, and two years following the Nailed shoot, he came out in winter of 2010 with The Fighter, which opened to excellent reviews, broke $125 million domestic, and landed seven Academy Award nominations including Picture and Director. He almost didn't get to make the film. It was shepherded into existence by Mark Wahlberg, who offered it first to Scorsese, who wasn't interested, having just explored the Boston setting with The Departed; next Darren Aranofsky signed on to direct, hired Christian Bale, and then begged off preproduction to do Robocop instead (which he also later dropped out of, favoring Black Swan). Wahlberg and Bale together turned to O'Russell, who then made the entire film in just 33 days on a paltry $11 million budget. When the awards started rolling in, O'Russell made his publicity rounds as the very picture of dignified humility, giving the world the picture of a repentant and disciplined craftsman intent on doing good work. Now, in 2013, more than enough time has gone by that we can see this is no act. How did this metamorphasis happen? I prefer to let the man speak for himself, as he does in this excellent Huffington Post interview. "I was overthinking things," he says. "My head was up my ass." After a difficult period involving some significant life changes, he found new inspiration and grounding in "a kind of filmmaking about a kind of person....ordinary people living operatic emotions. Lives, predicaments and survival....I stay hungry like it's my first film or my last film. We mean everything in these films from the heart as much as we can." Indeed, there is a palpable sense of unpretentious excitement in these three latest works of his. The highly mobile camera seems wired into the accelerated pace of the characters' inner lives; it moves as if completely untethered, gliding past faces and singing through rooms. Steadicam operator Geoff Haley deserves praise for making a punishingly difficult task so seamless. There's a high-energy joy to the camerawork not unlike that of Scorsese or '90s Paul Thomas Anderson. As well, his aforementioned focus on the working class is a particular standout. A great majority of films are either about the very rich, or the very poor. Not everyone is a graphic designer with a condo in Manhattan, or a backwoods alcoholic in West Virginia. Who makes films about people who drive 1995 Honda Civics? O'Russell's three newest pictures have in common their interest in the working class, and I find this incredibly refreshing. He invests the films with an energy revealing how real and immediate ordinary lives are. Each of the performances in Hustle (incredibly, all four leads are nominated for their respective roles) is rich with nervous energy and carefully observed details. Note the enthusiasm with which Bale talks about his dry-cleaning business, or the casual brilliance of the intertwining narration when Christian Bale and Amy Adams' characters first meet, letting us in on each person's private thoughts. The film is a positive deluge of such moments of creativity. Each film expands in scope from its predecessor, and Hustle is the largest yet of O'Russell's new phase, with its multiple relationship dynamics and mechanics of the con. It sets itself apart from- and above- other con movies in being more focused on character than plotting; because of this, the film will hold with time. Most great films are character-based. Don't listen to those who tell you story is everything. When the plot is the focus of a film's text, it loses value on repeat viewings because we already know what will happen. The drama of humans learning, behaving, and misbehaving is endlessly more fascinating. We watch Citizen Kane over and over not because of how much we like the story developments of a newspaper tycoon's business falling apart. Nobody remembers the story progression of Kane. It's the downfall of the character and his tragic transition from childhood to material success that captivates us so. We are people, and are thus fascinated by the lives of other people. American Hustle knows this, and carries it all off with an unaffected aplomb. 9. Before Midnight (Linklater) The third in a trilogy, following Before Sunrise and Before Sunset, exploring the romance between lovers Jesse and Celine (Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy). Each film is set and was filmed nine years apart. Trailer. In September of 2012 the news broke that Hawke and Linklater were "in the writing stages" of Before Midnight, working out some ideas. "If it works out, we'll film it, and if it doesn't, we won't. It's not really worth talking about. I'm just here developing," Hawke said at the time. Just over a week later they announced that they had actually already finished the film, and were taking it to Toronto! The film has been riding a wave of accolades ever since, and deservedly so. Before Midnight contains the best special effect you'll see all year- and by that I mean the acting. As with the previous two films in the trilogy, Linklater trains the camera on his actors and lets the film roll, and roll... and roll. He'll use a full magazine (about ten minutes) on one continuous shot of the two leads talking. There's one such scene early on of Delpy and Hawke in a car. The complexity of the dialogue they're performing would be impressive no matter how it was filmed, but to see the actors read it out with no breaks is staggering. The unbroken take is one of the last proofs of actuality in cinema. When Buster Keaton did all those physical feats of derring-do he was so adept at, we looked on in shock and awe, since we know that's really him on top of that train. This feeling of being stunned by cinema's ability to document has waned, and is today all but gone. We assume technical wizardry is involved whenever confronted with amazing imagery onscreen. Have you ever seen a sunset in life so beautiful that, were you to see it in a film, you'd be convinced it was a fake? During the filming of the climax of Tony Scott's Man on Fire, which involves a man walking from one side a bridge to the other, a volcano some distance behind the actors suddenly erupted. Initially Scott was thrilled- what could possibly be more dramatic? But upon looking over the rushes, Scott saw that he could never put that footage in the final film because, in his words, "it looked like a damn Disney movie." It was real, but our belief in the veracity of the film image has largely evaporated. Nobody would've believed it. However. The unbroken take is a very hard thing to replicate using digital effects without being very obvious. We know, watching the opening of Touch of Evil, or The Player, or the climactic nine-minute shot in Children of Men, that what we are seeing is undeniably continuous. We can see, in the famous seventeen-minute dialogue shot in Steve McQueen's Hunger (what is now simply called The Scene, which contains 28 pages of dialogue with no cuts; the camera was adapted to hold a longer film reel), that we really are looking at two people talking for seventeen minutes. It stands in contemporary cinema as one of the last hallmarks of truth-telling- there are no cuts to hide behind. While it's possible to blend shots together in post (Spielberg's minivan shot in War of the Worlds does this), such instances are rare. The whole point of a continuous take is to show that something is real. All the Before films contain plenty of long-running shots, and they're a joy to behold. Many have said acting is the best special effect, and that truism is on full dsplay here. Of course, viewers of Sunrise and Sunset will not be surprised by this. Midnight is shot and performed in the same impeccable manner as the previous films, once again using dialogue written- not improvised- by the actors. What can we say about this latest entry that sets it apart? Before Sunrise contained the budding excitement of burgeoning romantic youth. Sunset found the couple nine years later, and showed the complexities and challenges that live alongside the beauty of love. Midnight, set a further nine years later, follows the arc of this trajectory, throwing us full-force into the mire of unhappiness relationships can become. Whereas unhappiness was but a faint glimmer in the first film, here it is happiness which is so relegated. Midnight is a sobering experience, but a truthful one. It pulls no punches in its depiction of the aching experience of collapse. I hesitate to reveal more except to say that with the exception of Bergman's Scenes From a Marriage, there is no more thoroughly studied and complete cinematic depiction of the full course of a human relationship than what is offered in this trilogy. I can't recommend it enough. 10. Dallas Buyers Club (Vallee) True story of Ron Woodruff, an electrician, hustler and rodeo man who in 1985 contracted AIDS and, through illegal means, helped thousands of AIDS victims get the medication they needed. Costarring Jared Leto. Trailer. McConaughey is a revelation here. The story allows for many moments of juicy scenery-chewing, not least of which is the moment when Woodruff discovers he has AIDS, and McConaughey makes the most of the role in a performance at once subtle, brash, and thoroughly lived in. His natural charisma melds well with the character's wily, high-energy self, and the resulting vitality centers the film and propels it forward. McConaughey himself was instrumental in the long and arduous journey of getting the film made, and his passion for the project is more than apparent in the performance. Jared Leto, as a flamboyant cross-dressing man who ends up befriending the notoriously homophobic Woodruff, is also magnetic, most of all in a scene in which Leto's character confronts his father. We expect Leto to be great, however. The world is still acclimating to the thought of McConaughey as one of the best working actors. After this film and his other performances this year, there can be no doubt on the matter. As well, Jean-Marc Vallee's (The Young Victoria) direction is as much of a surprise. It isn't simply competent, as many actor-centric awards pieces are (Beautiful Mind, The Queen), but noticeably and effectively creative. To be frank, I wasn't expecting this. Many fourth-quarter dramas find themselves overpraised critically because the language for critiquing acting and writing is well-worn, since those disciplines have origins in other art forms. Film critics often hail from journalism or literature backgrounds, and are primed to analyze these components. They're thrilled when something is strong on themes, dialogue and performance. Much less often do they have experience with the filmmaking process, or an understanding of direction, cinematography, and editing- those elements which truly set film apart, and are every bit as important. When the (stellar) reviews became coming in for Dallas, a film by a little-known director, I was expecting something strong on narrative and performance, but not much else. I was wrong. This is more than an acting showcase. Vallee manages to get away with transforming important subject matter into a wild, entertaining ride. His aesthetic sensibility is rich and propulsive. He uses the 2.35 frame well, making the film seem larger with strong, muscular compositions. The images are drenched in soft pastels and muted warm tones, evoking a time period without over-relying on costumes and cars to remind us where we are. He'll use color to set a mood, allowing the dialogue the freedom to explore other concerns. Some of the film's best moments are the brief occasions of silence in a loud, chaotic life- Woodruff alone in his car crying, hiding behind sunglasses and bravado. Vallee centers him in the composition here; usually Woodruff is careening around in the frame, or pushed to one side. His placement in the frame is linked to how he feels at that moment in the story- confident, exposed, nervous. Great films do a lot of their communicating visually, and Vallee's directorial choices are no exception. The spare use of music is commendable in its own right, and all the more compelling when used. There is a vigor in this film that is undeniable. When a man can overcome his prejudices and open up his worldview, while also doing good for others- really, what could be more rejuvenating to witness? It's not surprising in the end that Dallas is deeply affecting. What's surprising is how utterly entertaining it is as well. |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed