|

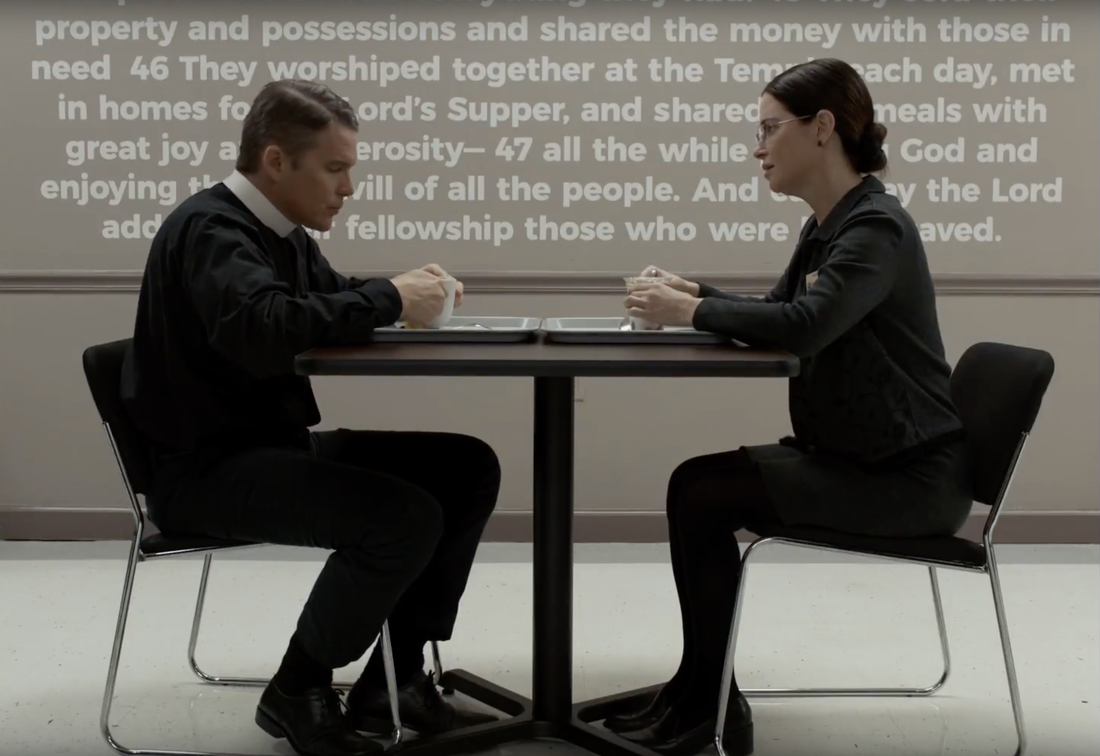

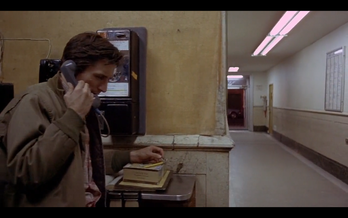

We become accustomed to the state of things as they were when we were young. At that time we're not so aware of the world’s constant state of flux. It transforms more easily than we do; upon aging we notice the world we knew as youngsters drifting away, bastions of childhood one by one fading, a bewildering relegation of everyday realities to treasured memory. I remember sodium vapor lamps. I recall textures of normalcy I no longer know the names for, may never have known the names for: the printers that printed with that scratchy-back-and-forth sound, onto those green and white sheets of paper that had the sprockets on the sides. The plastic preschool chairs with the three holes in the back. Color schemes left over from the seventies, ochre and yellow and orange and brown. Overhead projectors with the roller sheets of plastic for writing on. Floppy disks. Wood panelling. The need to remember where pay phones were, and to carry quarters for which to use them. Film. Those are the generationally specific ones. There are also the universals: your elementary school, now demolished and rebuilt; the trees under which you played, now withered stumps. An Astroturf soccer field that was once dirt, unkempt and sandy, just the way you liked it. The inconveniences which are no longer necessary but which you take pride in, because they once gave you character. Logically, you can see it isn't just your generation who faces this issue. But because this is, for each of us, our very first time living life, it feels unique. Why are the bright stars of our landscape dying? This is where a certain breed of despair takes root. Pile on our contemporary politics and environmental concerns, and you've got a recipe for teetering psychological disaster. It is a terrifying void, that existential pit. The exhaustion of having to continue adapting and acclimating on so many levels, the way we did so naturally as children, doesn't make things easier. We fall short of our earlier selves. What to do? Paul Schrader's new film, First Reformed (watch the trailer), is about a pastor (Ethan Hawke) wrestling with this dilemma on an intimate and profound scale. The spiritually vacant megachurch near his tiny parish certainly comes up short on answers. I had to see the film twice before realizing the first action we see the megachurch pastor perform is a corrupt one, so casually is it executed. Schrader's portrait of megachurches in all their sterile, corporate glory is quietly damning, but it's a sidebar. Taking aim at the religion-as-team-sport ethos is almost too easy as the main subject of a film this probing. Schrader, who wrote as well as directed, has larger concerns on his mind, and his protagonist's existential crisis is beyond the purview of what faith systems are able to answer. The pastor's conundrums are those we've all had, a confusion based on the original human question: Why? There are many elements I love about this rigorous, unsparing and rather perfect exploration of the bleakness of blackest despair and what to do about it. One is its implication that we often already know the answers, but have to come around to them before we know them fully. As Tolstoy wrote, much philosophy is thoughts you and I have already had, just expressed in better language. Another is the ruminative directness of its language. It's no surprise Schrader loves Dreyer and Bresson (at only 24 he wrote a seminal book on them and Ozu). First Reformed is a companion piece to his 1976 screenplay Taxi Driver in more ways than I dare reveal here; suffice to say both are about lonely men writing in diaries about worlds which they no longer understand. Conversations– notably a ten-plus minute barn-burner of conflicting ideas exchanged between our pastor and a young depressed environmentalist early on in the picture– run longer, deeper, more probing than movie conversations normally do, with not just one point to make but several. Formally speaking, there are a few aesthetic components Schrader here employs which make the film a different experience from anything else released this year (film critics almost never have filmmaking training: you'll find better writing about First Reformed's themes elsewhere, but you've come to the right place for a discourse on its aesthetics!). One is planimetric staging. I know. You've never heard of it, but you've seen it. Wes Anderson is its most famous progenitor: the action is staged parallel to the picture plane (lens), often in front of another parallel element, like a wall. From Anderson's Moonrise Kingdom (left) and The Darjeeling Limited (right): The resulting lack of depth is decidedly un-cinematic, more akin to a diorama than anything else; but it recalls the tableau, and painting. As a formal gambit it's a risk, in deemphasizing rather than emphasizing the illusion of depth in film's two-dimensional format. But its rarity of deployment makes it unique (for some reason it's especially rare in international films), and here fits the subject matter in suggesting pre-Renaissance painting and the same religious and ethical questions that were being asked even then. Schrader is limiting himself by setting such a formal constraint, and he doesn't stop there. He's spoken in interviews of wanting to create a "lean-in movie," which by its withholding draws us in. This is evidenced by the above, the absence of score, the withdrawn nature of Hawke's performance, and more: Usually, you want to cut from one shot to another on an action– in the middle of a cup being lifted to drink, for example. They call it match-on-action cutting. It's at once more dynamic and more invisible, more seamless. Schrader goes for a simpler route, cutting in between actions only. Recalling Dreyer and certain Bergmans, he invites an atmosphere of spareness in cutting to another face at the end of a sentence, not during it- a no-no in film school, but as ever, a rule made to be broken for the right reasons. The film furthers its sense of austerity with what's called compass-point editing: the approach where successive camera angles are either zero, ninety, or 180 degrees offset: It feels mathematical, restricted, like the environment our pastor feels stuck inside. Darren Aronofsky employs this technique for different reasons in his The Fountain (2006). An advantage of setting up these formal consistencies is the opportunity to make an impact by breaking them once they've been established. When at a crucial point we get a three-quarter angle on Hawke's face, against a background that's not parallel to the lens, we feel it; here is another example. I don't expect the audience to think, "good heavens, he's broken from planimetric staging and is cutting at 75 degrees offset instead of 90!"- but I do think they'll register, subconsciously, that something's different. The two times Schrader breaks completely from compass-point editing, the effect is transcendent. Viewers will, however, notice the unique aspect ratio. Most films nowadays are either "flat" (1.85:1) or "'scope" (2.39:1) widescreen. Here we return to the pre-1953 standard, the boxy 1.33:1 ("academy") ratio: Basically a square, it stands out from the rectangular compositions we've become used to in cinema. Faces and bodies fit into it differently, and different things get emphasized. It's a touch claustrophobic. Its narrowness means usually only one visual item of interest can occupy the screen at any given time. Andrea Arnold, who also uses the ratio, calls the academy ratio more “intimate”: It is not a popular format…I loved the fact that it’s the entire 35mm negative, you’re not cutting anything off. It’s square like the negative. There is something honest about that. It’s like you’re projecting the negative, it’s there, there it is, you’re not doing anything else to it, that’s the way it is. I think it’s also a very beautiful frame for one person. It is a portrait frame. My films are generally from the point of view of one person. I think it’s a very respectful frame. I keep using the word respect and I don’t know why I keep saying that, but that’s what it feels like to me when I look at somebody framed in a 4:3 frame. It makes them really important. The landscape doesn’t take it from them. They’re not small in the middle of something. It gives them real respect and importance. It’s a very human frame, I think. I think that’s the main reason. I don’t know, but I think. You can also see more sky, but I think the other one is the real reason. From her Wuthering Heights (top row, lower left) and Fish Tank (lower right): I'd like to highlight two shots from First Reformed in particular. The opener will make sense only in a theatre; faintest glimmer of a tiny crucifix at the center of the deep black screen won't even be visible in any other environment. It's there before you see it. As the shot fades in, we see the shape is a small cross atop an ancient church spire. The composition includes the whole church; We can see it is a small, modest affair, but from here it looks towering. The camera pushes in, keeping the bottom of the building and the top of the tiny cross within the frame, pushing in closer– until it clips the crucifix out, pushing that small but loaded symbol out of the top of the frame, as if to say: that's not where this film is going. The other shot is a restaging of Scorsese's famous lateral dolly shot in Taxi Driver, where the camera tracks to the right from Travis Bickle, feeling lonely on the phone, to an empty hallway; transitioning from a picture of him to a picture of how he feels. First Reformed also has a lateral tracking shot that shifts to the right– I won't spoil which one it is– but this time the lonely person in the frame moves with it, and the "hallway" isn't empty, but involves an important character beckoning him, the one who will have the answers. In this way it's more hopeful than Scorsese and Schrader's 1976 vision. These and other stylistic elements combine to articulate a very interior, subjective environment of our protagonist's psyche. There is something profound to me in watching what Schrader calls the "man in a room movie;" the eternal question of a (wo)man alone in a room, with nothing but their own thoughts.Small wonder the guy likes Bresson and Dreyer; we can find antecedents in Bergman (Winter Light comes to mind), and Schrader's own Light Sleeper and others. We experience life singly, as individuals, and it is when alone that the big questions loom largest.

Schrader literalized this best in Taxi Driver's most famous scene, in which Travis Bickle accosts someone repeatedly– himself, in a mirror. That film and this both feature a man we're asked to identify with... until we can't. It's a bold maneuver, to present such a highly subjective view of the world, through a set of eyes we at first sympathize with, but which go too far. In both pictures Schrader captures the line between sanity and insanity as ambiguous, the fuzzy place where psychosis breaks from mere radical thought. He touches on another ambiguity which warms my heart (this paragraph will make sense after seeing the film): a supernatural being would probably not discern between the natural and the supernatural. We define those separations from our limited view. From their perspective, it would all be natural. Likewise, would a being existing after death make a meaningful difference between what we call being alive and what we call being dead? Or would the division point rather be hazy, indistinct, maybe just plain unimportant? What I love most about the film is its daring to suggest a solution– two, really– to the fundamental question it poses. It's a universal question, and we can take some comfort in the fact that it's not a new one: all cultures in all time periods in all history have all thought they were living during the end times. They've all really believed it, too. --- Images courtesy A24, Columbia, Fox Searchlight, Focus, Indian Paintbrush, Film4, Oscilloscope, IFC Films.

2 Comments

Kendrick. Was that him? Even twenty miles an hour can seem too fast, what with all the glass and foliage in between, not to mention our opposing movement pathways and his distance from my bus. I was gliding north on Rainier, nearing the Ethiopian Community Center, when a shadow beneath the trees caught my eye. I know that gait. A figure glancing past on an evening sidewalk, long shadows now, just getting to where I could make out his profile. Yes, it was him.

I honked softly, a tap two times. He turned– my hand in the air, a salute– and it landed. Our eyes locked at the last possible moment. The next day he was waiting at Holden Street. "Mister Kendrick,” I declared, like an MC announcing his guest. “How's life, man?" "'Sup, how're you. You still modelin', bro?" It took me a moment to put together that he was referring to the ad campaign* I’m featured in. “Ha! Somethin' like that! Somebody takin' pictures of me out there, I don't know who…" "Just like that, kickin' it! Gettin' it said! Guess what though. You deserve it." "Man, I appreciate you sayin' that. I hope that's true." "I know it's true! I want everybody to prosper, bro. Prosperity is for everyone. That mean sooner or later I got the prosperity." "Exactly, it's an additive thing, for all folks. Everyone deserves it." "Everyone deserves it, just like that, man. E'ryone should get a turn. Iss good to see you. You blew at me the other night, bro." "Yeah! I was like, 'that's my guy!'" “You know what," he said. The sharing voice. "Some things touch your heart. Tha' touched my spirit, man.” “Thank you so much. We gotta look out for each other,” “I know man, tha's what we got, bro! That's all we got, man. We have to coexist–” “Exactly. We have to figure out a way to make this whole thing work." Hafta. Our words, molding themselves into the regional vernacular, of their own accord. There’s a linguistic fascination in ‘hood cadence being comparatively consistent throughout most metropolitan U.S. areas;** I picked it up from my days in L.A. The sort of thing that sounds truly awful if you try to fake it, but which rolls right off the tongue if you’ve lived a certain somewhere. I feel like I have to hold myself back sometimes. They don't know where I'm from. “Jus’ like that," he said again. I'm sensing a catchphrase here. "I can’t wait to, I wantchoo to meet mah little girls, man.” “Oh yeah, bring 'em on!” “Ah got three daughters, and they as cute as a bug. Paradise, Yum Yum, and Kennedy.” “What's the middle one's name?” “Yum Yum.” “Yum Yum.” “Tha's her nickname,” “I love those names! Paradise, Yum Yum, and Kennedy.” “Jasmine is her birth name, but as soon as tha doctor put her in my arms, we jus' instantly bonded, I said that's my Yum Yum.” “That's beautiful.” “She as cute as a bug, maaaaann… you know what? It's good to see a... it's good to see a good… man.” He chose the final word with care, and said it with emphasis. “You a good man, bruh.” I had an idea of what he meant. It isn’t the first time discussions of masculinity have come up in the ol’ neighborhood. The discussion in more monied circles these days is rightly focused on the need for equal treatment of women, and the urgency, at long last, to take women’s voices seriously. Kendrick and others are highlighting an element that won’t become part of the cultural conversation*** until later– the flip side of the coin. What does it mean to be a good man? Is there such a thing? How should a man function in a society where men have long been expected to be in control (though most of them never will be), fix everything, to not take part in communities but rise above them, who are raised and encouraged to be out of touch with their emotions, and who generally feel emasculated by the impossible expectations they’re held to?**** Perhaps by admitting we don’t have all the answers; embracing the vulnerability of letting down our guard, sharing in the “uncool” emotions of joy and fear and wonder we only pretend we don’t feel; recognizing that equality is not a zero-sum game but is instead additive, as Kendrick alludes to above. Prosperity shared helps everyone. It’s okay to celebrate something sensitive, and call it out as beautiful; that’s what our friend K-Money, ruffled black denim and voluminous black print tee to match, bald head shaved over a chain necklace– that’s what he was impressed by. “Right back atcha,” I said, “especially like, talkin’ 'bout Father's Day and stuff,” “Jus' like that man, thank you very much." He paused. "So whatchall… what route you was drivin’ before you came back to drivin' th' 7?” “Yeah I was gone– doin' the 41, 65, lil' bit further north,” “Okay, goin' through Lake City?” “Exactly. And those are fine, but man, I had to come back here. It's just, I don't know how to explain it. I feel… this is where I belong, you know? Where it all makes sense. I feel right comin' out here.” “I appreciate tha’. I'm tellin’ you man, you will always prosper, bro. ‘Cause two things that you are: you are so humble, and you are so thankful.” Effusively thanking him, I added, "humble and thankful– you know, I remember you and me talking about that one night like those are the two things–” “If you keep– those two things, I promise you. In time all things wi' be revealed. Ey, what time you leavin’?” “Um, fifteen. Fourteen minutes.” “Koo.” “Alright man. Always good, Kendrick.” “Al-ways!” After the alotted time had elapsed, he materialized yet again, this time bearing gifts from the neighboring Rite Aid. “Donald Duck orange juice,” I exclaimed, as he handed me the bottle. “How'd you know I love this stuff?” “‘Cause you a good man, bruh. No matter what, you always– the thing I know about you? Is you treat the neighborhood good, man.” “Thanks, man. I love this place.” “You know hatta serve. That's next to Godliness, man.” He gazed out the window now. “Servin’,” he repeated, mostly to himself. I would see him two days later, once again a figure in my periphery as I drove past. Was it too soon to honk hello once more? No. He was off the sidewalk, stepping through a dishevelled front yard toward the main entrance of a walkup. The bus moving past, his concentration elsewhere, my tap-tap travelling towards him, the sound taking form in his mind, given meaning, a signal a salute, him turning, me turning away, his eyes getting closer, his hand pulling back from the doorknob up into the air, knowing before locking eyes who that probably was– –and there, right there, a fraction of a fraction of a second. We did it. We stopped time. Made it special, a freeze frame lingering long on a warm summer night. --- *I still haven't watched this video.... **For more on African American Vernacular English, as it's called in linguistics, refer to this paper, especially section 3 (structures in urban AAVE grammar). It has some interesting bits about how rap has incorrectly co-opted certain grammatical elements of AAVE and why, as well as a new tendency toward minimizing certain AAVE grammar in later age, due its now disproportionate aspect as a marker of youth culture. If you don't want to turn your ten-minute coffee break into a 90-minute lunch, try this shorter but still terrific blog post summarizing AAVE history and characteristics. ***It's an exciting time, but it's not a new time. I haven't been alive long enough to live through multiple such movements, and while I'm incredibly enthusiastic about the direction we’re moving in now, I find the perspective from those older than me sobering, and instructive. “I remember thinking the same thing during the Clarence Thomas hearings, that the cultural moment had come and everything would change,” pioneering psychologist Louise Fitzgerald recently said. “But here we are twenty-some years later when people are suddenly rediscovering yet again that sexual harassment exists.” In her landmark tome Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist Susan Faludi delineates the principal complaints women aired on inequality during the 1970s. They're almost exactly the same as the ones we hear today. I'll refrain from repeating the line about history repeating itself, because I do believe incremental progress is being made, but having entire generations who've never read The Hite Report and have no idea who Betty Friedan is probably isn't helping. More for the reading list.... ****I wish I could take credit for these insights, but they come from Susan Faludi. I’ve recommended her writing on my blog before (including thirty seconds ago in the footnote above, ha!), but I can’t help it. Anyone with the slightest interest in learning about gender issues from something besides a 101 class and a bunch of BuzzFeed articles will drink up her two 600-page mammoths, Backlash (about the backlash against Second-Wave Feminism in the 80s) and Stiffed: the Betrayal of the American Man (about male emasculation and the assumption of male dominance, with a focus on the 90s). They’re simultaneously devastating, difficult to get through, and impossible to put down. She channels her necessary frustrations into a level-headed calmness of prose that leads to insights our extremized culture tends not to reach. Faludi was most recently a finalist for another Pulitzer for her memoir In the Darkroom, about her father coming out as transgender and undergoing reassignment surgery at the age of 76. In the post below, I mention a difference between northern and southern bus service here in Seattle, and was going to explain further with a footnote. But this is too fascinating for a mere afterthought. It’s time for some serious tech talk. I like long, busy trunk routes like the 7 or the E. Those usually run often. Driving out of North Base has reminded me of another world; the dynamic is very different when there isn't another bus for an hour. As I mention in my recent KUOW interview, I drive them differently. If someone's running for an infrequent route, I wait, no matter the circumstances. I tend not do that on the more frequent 7/49. I've waited ten minutes for a bus. Not a big deal. An hour, on the other hand.... Your bus is rare. It feels more special, more important. You really have to make sure you get everybody. The people you pick up may have been waiting for a long time, and may well have oriented their day's plans around your schedule. I recently did an outbound 308; there’s only three of those all day, spaced an hour apart. You better believe I craned my neck looking for those last-minute stragglers. I wonder what my 7 riders who now live in places like Haller Lake and Ballinger Terrace make of the contrast in bus service. If they once lived in the Central District, the 3/4 took them into town every 8 minutes, with last trips at 1am (now 3am); the 7 has ten-minute headways and runs 24 hours; but the 331, where I've noticed a number of familiar faces... runs every thirty minutes, with last trips at seven P.M. and hourly Sundays. If that's not a lifestyle change, I don't know what is! To the used car-lot we go.... I want to specify these service levels as endemic to North King County (and other parts of the County outside the city), not North Seattle. North Seattle has surpassed South Seattle in having the best bus service. Since the UW Link restructure, nearly the entire network up there has 15-minute headways or better, and the routes are thoughtfully interconnected and conveniently thru-routed,* with 15-minute east-west service (nonexistent in South Seattle at the time of this writing) and a lot of night service that remains frequent. The north-headed 5, D, 40, 41, and 62 all maintain 15-minute service until about 11pm nightly. That’s fantastic. Of south-pointing service, not even the 36 does that; only the 7. Further concrete examples of this divide can be found in the 26/131 thru-route, on which the northern half (26 to Northgate) runs more frequently at night than the southern half (131 to Burien), despite the 131 being more used and needed. The very same goes for the 28/132, 24/124, and the 5 and 40 vs. the 120– the 5 (Shoreline) has frequent service til 11:30pm and all-night Owl service, whereas the 120 (Burien) goes to thirty-minute service at 8pm and doesn't run all night, despite being more crowded at those times. Another mystery is the 5/21, famous among drivers for its outdated and unrealistic schedule* on the 5 part, which offers 15-minute service on the 21 part until 10pm… on Sundays only. For the rest of the week the 21 stops frequent service at 8pm. Go figure.** You may ask, as I do: why does North Seattle get better bus service when South Seattle is obviously more in need? Is Metro catering to choice riders and not transit-dependent ones? No. The answer is multifaceted. On one hand, I think it's important to be mindful that sizable chunks of the population served in South Seattle do not have as ready an access to the internet, ease with the English language, or knowledge that speaking out can effect changes in transit planning. There is the agency of a population fluent in English and online, better equipped and more inclined to voice their concerns. A lot of countries our friendly neighbours come from don't have governments who thoughtfully alter transit service in response to customer feedback. You have to know it's even possible before also having the time, resources, and know-how to do so. Nothing's more tiresome to me than transit geeks who don't live in the South Side or South End proposing nonsensical alterations to real-world lives (I once read an article that actually thought cutting the 7 at Othello was a good idea, and another that deleting the 4 was okay because people "can just transfer" to get from Judkins to Swedish, taking 2 buses instead of 1 to travel a distance of 2 miles). I don't wish to discount all their opinions, and admit I'm swayed by the human element: I actually know the people who use the service out there. But such proposals are not a suitable replacement voice, and fit within the definition of gentrification: changing a neighborhood without the consent or participation of its residents. More boring, less talked about, and far more significant is that the problem is complicated by funding elements. It's not because Metro doesn't like poor people; pardon me while I roll my eyes at the very idea. More on that in a moment. Routes that leave the city limits cannot be financed by the same revenue streams as those that stay within it. Several agreements stipulate that funds can only be applied when a specified majority percentage (80% at the time of this writing) of the route exists within the city limits. Everyone knows the 120, 124, 131, and 132 all have more people on their night trips than the 24, 26, 28, 33 etc, but what those 100-series routes also all have in common is that they travel significantly beyond Seattle city boundaries, and as a result of funding allocations their riders don’t get the service they need. Those 124’s are packed at 1am, and they shouldn’t be.*** That’s all about to change, though; SDOT plans to relax its percentage thresholds regarding city limits to 65 percent, not 80. That bone is very much for the E Line, the most heavily ridden single route, and which has been artificially held back at lower frequencies at night due to this soon-to-be-cut red tape. Same goes for the 106 and 120 in short order. Whispers tell me of improvements in the Fall. I write above about a trigger-happy attitude among certain transit enthusiasts to monkey around with service they don't use, because reorganizing routes on a map would look cool. I'm thankful that Metro's administration comes from a different perspective, abundantly evident whenever I talk to them. It's a perspective rooted in concern and care for the underserved. The previous administration at Metro and the current one, both of whom I feel fortunate to know personally, care strongly about the working-class and low income. They've imposed stipulations which require planners to serve certain demographics and provide lifeline service to those who need it most. They focus on unified treatment and are careful to avoid any development of class stigma in modes of transit offered. They don't cut back service on a route just because of security incidents, or avoid serving otherwise challenged areas. They just held an audit on the Fare Enforcement program and concluded it was unfairly disadvantaging the homeless, and have already taken steps to improve those issues. I may have things to say about scheduling,**** but when it comes to overarching vision, within the numerous restrictions they're up against and alongside the multitudinous interest groups involved, Metro's beating heart is in the right place. I know it would be more exciting to reveal that some sort of high-up institutional corruption was afoot... wait, isn't this more compelling? A case in point: The A Line, which serves Tukwila, Sea-Tac and Federal Way, was and is Metro's inaugural RapidRide route. The B Line corridor, in Bellevue/Redmond, was actually ready to go first, but Metro knew that would send the wrong message. The best and most high-profile service type couldn't debut in Bellevue, for Heaven's sake. It would send an elitist message of who Metro caters to for the rest of RapidRide's days. The powers that be held off a short bit to allow the intensely working-class Pac Highway corridor to be the first to have RapidRide. "'Cause this service is for the people," a staffer told me with pride, explaining the story. For the people. Not the elite, not where the money is, but everybody. I don't need to point out how unusual this outlook is for a large organization. You understand. I imagine this is possible because Metro is not a business but a service, provided simply to improve quality of life and economy for everyone. That's their bottom line. You've gotta love these guys. It's one of my favorite things about working for Metro. I'm not sure I'd be here if it were otherwise. It's what I think about every time I see an A Line drive by. Bureaucracy and politics have a way of gnarling things up, making that hard to see and harder to realize. We just have to keep on keepin' on, getting those folks in the southern reaches some comment cards, and continuing to work away at that red tape. Footnotes:

*This is a scheduling problem more than a planning one. Passengers love thru-routes. Everyone hates transferring, especially at night (a major percentage of my 7/49 crew travels through both routes). I know how expensive it is to add 5 minutes to every northbound 5 and southbound 21, but it would be cheaper than breaking the thru-route and better than inconveniencing people. **I’ve got a shiny new dime for anyone who can explain that one to me, or why the 41 has thirty-minute frequency until the end of service… on Sundays only, or why the 41 shifted its last southbound trip leaving Lake City to before midnight… on Saturdays only, rather than 12:20 like the rest of the week. That was the lifeline trip for the Fred Meyer employees there, who get off at 12. I know people who’ve had to leave their jobs there as a result. ***Planners, while I have your ear: three cheers for extending the 124 to Sea-Tac during non-Link hours. I’ve used the service myself and much appreciated it. But if I may: what of the infamous 2.5 hour gap, during which there is no northbound service to downtown from 2:30am to the first Link at 5am (worse on Sundays, 6am)? Two more northbound Sea-Tac-starting 124 trips would be ideal, but even one to split that 2.5-3.5 hour time span would make a difference, and allow us to say we offer 24-hour service not just to 24-hour Sea-Tac, but from it. I’ve come this close to missing that last 2:31am trip.... ****Schedulers, I love you. But when articles like the one linked above imply we have finally have enough funding to address some things... fixing runcards can be done during our current driver and equipment shortage. Come to the bases more often, please. The lack of transparency between those scheduling the service and those operating it (not to mention those riding) creates enormous friction and misunderstanding. Here's what I would share from experience:

As you may know, I've been taking a break from the 7/49 for art-time-school reasons detailed here, instead driving suburban routes in North King County. This whole North Base adventure (I haven't picked up there since they deleted the 358) has been nothing if not charming. The operative word is pleasant. Five years ago I might've said boring, but there's no reason to put a pejorative label on transporting low maintenance, gainfully employed north-end residents. The generally subdued air has its own pleasures. After four straight years of driving the 7/49 exclusively at night, I've been downright shocked at the sheer numbers of people up here who are healthily equipped to take care of themselves. They do things like follow rules, pay fare, and even wake up at terminals... in droves!! Such responsibility! I'd look around in confusion, almost disappointed. Where was I? What town was this?? Truthfully, it's been a thrill to be reminded how well so much of the population is doing. I'm not just referring to affluent white folks, but the steadily growing immigrant presence in North King County, many of whom are faces I once served on the 7, but who have been pushed out due to the gentrification happening in Rainer Valley. (I can recall an even earlier time when those I knew on the 7 were people I once served on the 3/4, back before the Central District bumped everyone further south.) Never mind the completely different type of bus service;* it's a beautiful place to live. I'm reminded of growing up in pre-Microsoft Redmond, backroads of immigrant families, that time when living in the suburbs had no status significance. Boomers will recall that buying a house and raising a couple of kids in somewhere like Leschi or Bellevue or Ballard didn't used to mean anything. The ostracizing spectre of class and the scarcity of resources causing it hadn't infiltrated this dynamic yet. They were just affordable neighborhoods. You didn't need two working spouses or an inheritance to do it. People moved here from California because it was– can you imagine? –cheaper! Why not raise your kid on a safe, tree-lined street, with a yard and dog and families as neighbors? We know all that has changed now, but there are sections of North and South King County where the 'burbs retain that unpretentious flavour, where a yard is just a yard and things quiet down at night. Don't pretend you don't love that. I've had a great time in this different world. It's quieter. It's easy. It's allowed me the mental freedom to focus on school and art. I was convinced I'd stay up here for one more shakeup, the Summer season, before heading back to my beloved downtown trolleys. That was my plan, right up until the night before the Pick. Then it happened. I thought I'd look over a few runcards (bus shift schedules) before going to bed. Picking for the next season is a big deal for bus drivers. It borders on a job change, and can affect so much of your life: different days off, times of day worked, amounts of overtime, new colleagues, bosses, routes, passengers, work sites, commute times. You think carefully about it. I knew I’d probably stay at North, but thought I’d peruse a few runcards. You know. Just to be sure. I clicked on the internal link for Atlantic Base, scrolling down to nights on the 7. I looked at the street names. I thought of the turns. The faces. The through-route to the 49. Jackson. Henderson. Broadway. Rainier Avenue, and the wire singing out behind you, sparking in the late evening, the sheer majesty of those things, sixty feet articulated, feeling every bump in the road, an emblem of a time and a place and the stop-start flow of life in flux, truly lived. A state of mind. A shiver of joy ran down my spine. Mine was the choice between comfort, convenience and ease, as opposed to feeling valuable, helpful, useful. Loved. Both are great, don't get me wrong. There's a time for each. But this wasn't something I needed to waste time actually thinking about. Do you know what it means to feel loved, like this? To be adored by those close to you makes you feel loved for being who you are. Nothing beats that. However: the joy that comes from an equalizing interaction with a stranger makes you feel like you belong to the entire human race. You're part of something massive and it's just like you, it is you, and it contains goodness. You, we. Same thing. You cannot get that sensation anywhere else, in any other way except through positive interactions with, specifically, strangers. That's why we remember those beautiful moments on street corners we've all had. And that's what the potential of inner-city bus driving is, all day. "You go out to one of those satellite bases, thinking you'll come back, and you just end up staying out there," I've heard so many drivers say. "The work is just too good. It's so easy." The words echoed in my mind, up until I started looking at these runcards. I recalled the Atlantic window man yelling playfully at me, when he discovered last shakeup that I was going to North, as he laughed away when I said I would return: "you're never coming back! They neeeeeever come back!" I thought of the genuinely disappointed look a dear friend gave me three months ago, someone who'd looked up to me and my writing and my enthusiasm for the people, who'd gotten through a difficult time in her work life by reading my blog. I’ve gone through a lot in the past year, and while I know it’s possible to grow, to break habits and form new ones, there’s a core in us that’s deep down, and it seems constant. I keep getting told it’ll dry up. I respond with this quote from Richard Linklater's excellent Before trilogy: “I read this study where they followed people who won the lottery, and people who had become paraplegic, right. You'd think that... you know, one extreme is gonna make you... euphoric, and the other suicidal. But the study shows that after about six months, as soon as people got used to their new situation, they were more or less the same.” We are who we are who we are, in other words. They say you never forget the ending of Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath; I came upon it in middle school, and was moved by the stark kindness shown to strangers in the book’s final moments. But what burned a deeper imprint for me has always been Tom Joad’s last words to Ma, where he explains why he needs to be where the action is, where everything’s going wrong. Maybe “a fella ain't got a soul of his own, but on'y a piece of a big one,” he says, echoing filmmaker Terrence Malick’s notion of humanity as a collective, and the fundamentally right sensation of contributing to that collective, those other parts of ourself.

Maybe that's what I'll always be trying to aspire towards. ---- Some more specific thoughts on what the 7 is and why I like it (and how I'm thankful for colleagues tolerating my nutty inclinations) here, from a night in 2015, and in the post linked above from a few months ago, as I was leaving the route. Looking for more 7 stories? Take a peek at the archives, on the sidebar to the right and below! Most everything on this blog from mid-2014 onwards is from the 7/49. Winter 2012 and 2013 are the 358, and the other seasons of those years are primarily the 3/4. *More on this in an upcoming post. I’m going to describe him, and then I’m just going to let him talk, let the scene play out, that it might resonate for you as it did with me. We’re on Aurora, just about about to turn off and go burrowing west into the quiet residential tracts. He boards in true Aurora Avenue garb– gray carpenters and a white t-shirt dirty from work or play, jailhouse tats emblazoned on his arms, once pale but now tan and coarse. Stubble-faced traveller edging out his fourth decade, tough but friendly, companionable even, with the bass-heavy grit of life in his voice. He knows how to meet you on your turf.

“I think my transfer ran out,” he says. “Gimme a second with these bills.” “Oh, just some coins is cool.” “Points?” “Coins. Just some coins, yeah. You’re all right.” “Oh. Thanks, man.” He's taken aback. I often feel I’ve seen more beautiful things with more regularity at this job than anywhere else: look at the face in his eyes now, the realization that he’s in a safe space, accepted. Among friends. “Hey,” he adds. “You know what? You’re all right.” “Thanks, man!” “Listen, I bet you hear a lot of stories but lemme tell you. Years ago I made a mistake.” “Okay,” “And I’m gonna to see my mom and wife right now for the first time in six years, we’re gonna have dinner.” “Wow!” “Then tomorrow I’m going on a thirty-eight month sabbatical. But I’ve got today, and I’m gonna have a great time.” “Oh man! Okay that’s fantastic.” “Yeah I, well I made a mistake.” “Okay.” A quick speaker. “I used to run with… you know, I was just downtown makin' a couple rounds. I wanted to say thank you to some of the guys down there. I used to hang out around you know UGM, Rainier Beach– I mean these are not guys you would introduce to your grandmother, lemme tell you. But I wanted to thank them for being part of my life and my journey, right? Now my mom wouldn’t appreciate them at all. But here’s th’ deal, I shook their hand I said ‘you treated me with integrity in my journey but I’m never gonna see you again, ‘cause if I see you again then I’m ‘onna cause trouble, make a bad mistake.’ But I shook their hand you know what they said? They pretty much said the same thing they said, ‘pleasure meeting you. You go take care your business and you go get your family.’ And these guys. These guys… and so I keep makin’ these runs right, on the E Line, I started hitting this wave of grumpy people, and I jus' got through with this one guy, just I mean… I mean I was like I should just take this guy and throw him off the rails but I’m like no, no, no. And he got me all riled up, and then I get here and now all of a sudden for some reason I’m at peace again, and to have you say that, I’m like you know what?” “Dude,” “Just so I’m tellin’ ya–” “That means a lot–” “Little things like that–” “–the details.” “Go a loooong way.” “What an awesome journey, man, first time in six years. And okay, thirty-eight month sabbatical–” “Yeah well what happens is I made a mistake nine years ago and… Okay I made a poor choice, thought it was quick fast, thought I was a gangster. So what I gotta go do is go back to face a first-degree armed robbery charge?" “Okay,” “And what happened was I got out, left DOC for the first time and got a job and got all this– but I left the County after nine months. I took a three-day violation and turned it into thirty-eight months, but you know what? I’m here.” It was a sabbatical. More jail time– and jail time for paltry regulatory reasons from the sound of it, pertaining to no new crime towards others… no one would fault him for being furious at the world, or hopeless, and yet– he called it a sabbatical. Would that I had a fraction of his temperance and perspective. He had one day with his family after six years, with another three away in front of him, and he wasn’t dismayed in the slightest. He talked about it like it was time to think and grow. Part of me wondered what had kept him extending the travelling violation. Love, perhaps? It must have been something worth it. There was no fear in him now, nor energy expended on any other negative emotion, no matter how expected– disappointment, frustration, disillusionment. I’ve met monks that aren’t this good. Did he read the Stoics during his time inside? Or did he and Epictetus simply reflect and conclude similarly, never mind the millennia separating them? Take life as it comes, and make the best of it. He waved back at me, one last time, clearly and genuinely invigorated for the evening that lay ahead, his gladness at our exchange, for what today meant. Here was a man who knew how to enjoy the present. "Don't think about it. Or else you'll end up going home. Forget's what happened, or what's gonna happen. Focus on what's happening now. The rest doesn't exist here."

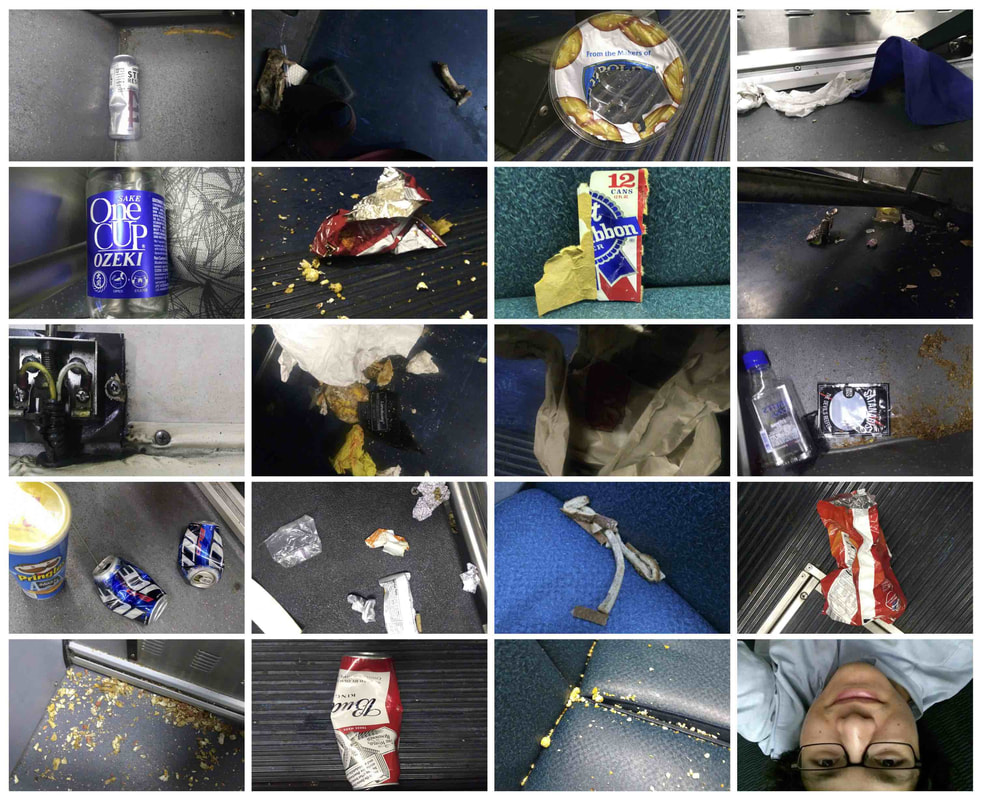

-A Perfect Day (2015), dir. Fernando León de Aranoa. Trailer. I won't sit here and try to tell you it's a great film. It isn’t. But it has an uncanny outlook I want to share with you. As other public service workers accustomed to insane environments will attest, there are not a lot of films that capture a certain unique and very valuable mindset that looks strange from the outside, and is hard to describe to others. Set in 1995, A Perfect Day is about humanitarian aid workers stationed in war-torn Bosnia. It's also a comedy. The entire picture concerns a small quartet's efforts to extract a corpse from a village well, and the unending parade of obstacles that prevent them from doing so. Outdated regulations, communication misfires, personal prejudices, and bureaucratic red tape from militias and well-meaning aid organizations alike thwart their every turn, and they expend great effort accomplishing almost nothing. An optimistically warped reader like myself will recognize the key word there: almost. How do you stay sane in an insane environment? How do you not go crazy with despair both intimate and existential? What works for our characters in the Balkans also works in the crazy world of on-the-ground urban public and transit service: You do what you can. The rest, you laugh about. You have to laugh. Don't go looking for logic in these parts. Don't think too hard about things, or ask yourself too many questions. It gets in the way of the smile you can give someone. And those do help. Just laugh about it, put in some effort, and be something other than a problem. You won't solve hardly anything, and that's okay. You're accomplishing more than you think. Above image courtesy IFC Films. |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed