|

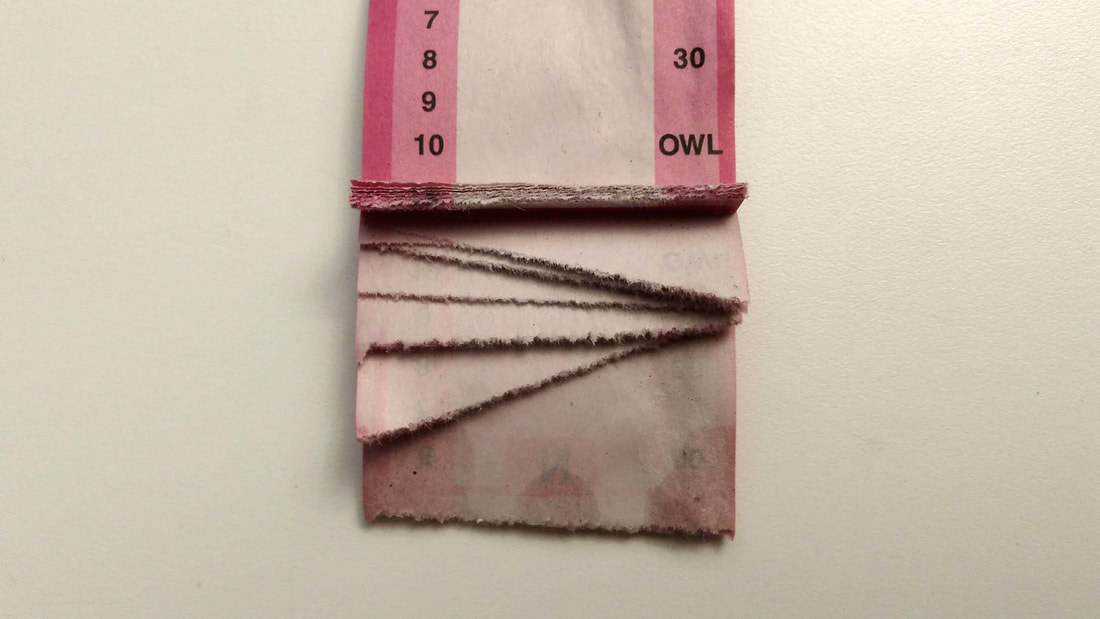

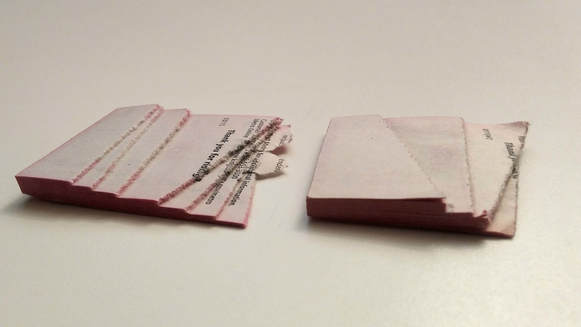

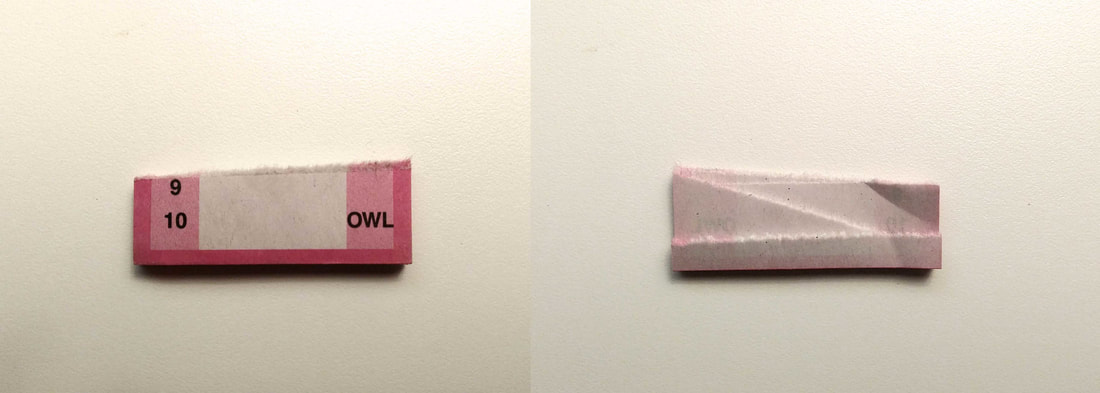

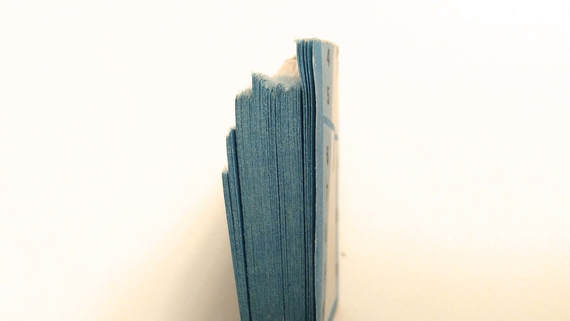

I used to save these. They're the bottom ends of transfer slips, leftover in the cutter after tearing them off for customers. I call them "transfer evidence," and they're exciting to me for what they represent. There's a sentimental streak in me that overvalues certain objects. We're always leaving people, or they're leaving us, and when we have the chance to say goodbye, we take it; transition looks too much like loss otherwise. We do what we can against the constant tide of reality becoming memory. This is where artifacts find their greatest value. They expand in their meaning, become more than themselves: the plain white saucer on my kitchen counter, Jewish, from World War II. The typewriter with the fading ink band; the patches on your jacket, darned by a family member, decades past on a cloudy Tuesday. The objects that didn't used to matter; how many memories do they now contain? I particularly like transfer evidence because of how much it reveals, collectively. Each torn sheet represents a story, someone's day, plans they had. Each paper is a person with a mission, infinitely different. Each diagonal tear position indicates a specific trip, and more positions indicate more trips. Some trips are busier than others, and that gets reflected here too, in the varying thicknesses of each diagonal: The day represented by the left batch in the picture above had more trips, but less people per trip, whereas the chunk on the right looks like just 4 trips, with the last 3 being very busy. My night shifts involve longer transfers and thus shorter evidence. The thickest strip is at the very bottom, of Owl transfers torn that night: This is a busy day. When I drove the 358 I'd use an entire book of 100 transfers in three hours: I no longer hang onto these like I used to, mainly for lack of space. As a hoarder I'm an utter failure, because I vastly prefer spacious and empty living areas. I can't keep everything!

But sometimes I'll still pause after the end of a long day, reflecting on that bushel of paper before tossing it in the blue bin, considering all they represent. Flipping through those little sheets. The jostled stress, the happy eyes, the students and mothers and lovers and sons, crowded together for only this hour, and probably never again. That was a lot of life out there that I just saw, I'll think to myself. Isn't that kind of glorious?

4 Comments

I've been out here long enough to watch people grow up. I've listened as they've built up concepts of self and culture I can learn from. Theo stood beside me now, once a high school student, now a thoughtful young man with the sort of maturity you don't often find till later age. He has the sober insight that can only be won from heavy disappointment. To fail, and become anything other than bitter: that is real accomplishment. I'll tell you more of his story later.

Tonight he's wearing a beanie and 70's-style gold frames, big, with Kanye-shaped fitted jeans and a dark jacket, not a Letterman but similar in shape. He's tired, and it lends him an unintentional gravitas– the soft spoken, world-weary African-American intellectual, but young and athletic too, dignified and hip all in one breath. It's hard not to like a guy who covers all the bases. We were talking about the track and field program at Arizona State when he pointed out another young man running for the bus– a white guy, unusual in this neighborhood, at this hour– running fast tonight, really sprinting. "Wow," I said. "He must need this one. He's puttin' in the effort!" The boy– probably eighteen or twenty– dropped his sweatshirt in his exertions and didn't even pause, racing ahead to the zone at 39th Avenue. The sweatshirt was in my path on the roadway, on my way to the stop. "Okay, we're gonna be super nice and make his day, because why not," I explained. I stopped the bus by his sweatshirt, jumped out and grabbed it, jumped back in to drive up and land at the zone. Perfect timing. Our new friend bounded in. I had a big happy grin pasted on my face as I held out his sweatshirt and said, "it's your lucky day...." My smile withered away. The young teen received his shirt without looking at me and stared wordlessly– at Theo. I haven't seen that much hate in years. The boy looked at Theo like you look at a rabid dog. Like you look at a spider that's too big to stomp out but you can't wait to do it anyway. He looked at Theo like it was crazy they weren't fighting already. I have a lot of friends, and they have many differences in ideology, religion, politics– but they all share one commonality. They are all kind. That's how my birthday blowout from two years ago, which featured all class, status, race and gender groups in Seattle, got along so well. They had a swell time. Only one ingredient was needed to make it so, and they all had it. But I still live in a cocoon. I forget the attitudes my friends have to tolerate, and what it feels like to take the brunt of hate. My friend L____, walking home in Greenwood– not Greensboro– the nice side of town, you understand– when a pickup truck of white frat boys pulls over to dump buckets of water on him and tells him to go back to Africa. My friend D____, hustling two jobs to pay off his loans from graduating the Art Institute and driving home from his real estate work, almost home in the innocuous suburb of Shoreline (not Birmingham)... when a young white woman cuts in from of him, parks, and exits her vehicle in traffic to scream much more than this: "Fuck you, nigger! You almost killed me! My life is more important than yours!" What do my friends have to tolerate, daily, that I only hear echoes of? I know so little. Should I be surprised when some of them act distant, or have a more potent perspective? Theo didn't mirror the hate. He kept a neutral gaze, soft, non-committal. That takes talent. The hateful boy walked past; he was the only white person in sight, and I got the sense he felt scared and out of place, perhaps thinking that demonstrating readiness to fight was a solution. Afterwards I looked at Theo, and Theo looked at me. I shrugged my hands in the air, and he shook his head, almost a smile. I didn't have to say what I knew we both innately grasped: Whatever, man. I wasn't going to let this be a teachable moment. If another person is sprinting for my bus and drops their sweatshirt, I'm going to do exactly the same thing. I'll pick it up, I'll wait for them, and default to a smile when they step in. I'm not going to let this boy's hate proliferate. I'm just going to keep on keepin' on, stayin' strong. Like Theo. He said, "what were we talking about?" Photos by Eleanor Moseley. Part 1 here.

There are different levels of thanklessness in filmmaking. You're watching the latest Oscar winner, or the latest direct-to-video Netflix production, and you're sitting there afterwards watching the end credits, as I like to do, taking a moment to decompress and process what you've just seen. Some people don't watch credits, but I find it hard to instantly transition from the trenches of World War I to making a cheese scramble. Plus there's all those names in the credits. Look at all that. Most people don't know what a best boy is, or a gaffer, or a second AC. We blink and move on. There's a level of thanklessness in that dynamic, but to a degree it can't be helped, and it's not the sort I want to dwell on. On a set, everyone knows what a best boy does and who the gaffer is. They're not invisible. It's the Production Assistants. Who are these friendly and harried people, running about the set on their own time? Bringing another carrier of coffee. Filling everybody's parking meters again. Carrying the ladders. Ordering the lunches. Taking out mounds of garbage. Fighting traffic as they rush run errands. Cleaning the location afterwards. All this and a thousand tasks more, as a volunteer: no matter the size of the production, PAs generally don't get paid. They're taking days off work to do this. Often you don't even know their names. You can understand how the smaller the production is, the more is asked of each crew member. My recent shoot was a tiny one, but the effort put into it was massive. Each PA did the work of what should really fall to several people. My script supervisor monitored continuity and confirmed shots and was a director's assistant and deputized to delegate the other PAs and and managed the extras and transported and relocated items from room to room and car to room and truck to car and blocking pedestrians and showed up on set as asked, just in case she was needed– on one day only to find the shoot cut short by rain. My craft services person selected all the food in careful anticipation of everyone's needs and supervised setup and takedown and wrangled the extras and cleaned the locations and ordered the crew lunches and packed the cars and blocked traffic during takes and enforced seventy extras to a quiet set. Did anyone on my film perform only one role? It's all so spectacularly thankless... and yet so absolutely critical to a film's existence. This thanklessness isn't exclusive to the PA role; it's just the most obvious there. They bear the brunt of representing it the most potently. A PA, scrambling to get a stack of pizzas for a crowd of hangry extras. The extras, waiting two hours in a cramped room while lighting is set. The gaffer and grip, working as quickly as they can with dangerous equipment, solving a thousand mini-problems the extras will never know about. The location owner bending over backwards to bring in security and technicians on their off days. The DP and focus puller, working out a complicated move the audience will only notice if it's done badly. The actors, spending hours working out a psychology and backstory only the most careful viewer will consider. You have to do this stuff because you like it. Because you like the people you're working with, the idea behind the project. The craft of it. Filmmaking is tied heavily to celebrity in the public eye, but you can't do it for recognition. It's invisible work. Directing is one of the last truly dictatorial roles out there. Realizing the authorial singularity of one person's vision by collaborating creatively with dozens of others demands the approach; a hierarchy is needed. Everyone who works a film set has at one time been a PA, and we all understand what that bottom rung feels like, but there usually isn't time to express it. You just hope they know, as I hope my crew knows, that I'm forever indebted to them for putting in the backbreaking effort necessary to make a film together. "I feel awful," I told a friend after one of the shoot days. Things had gone spectacularly well, but the euphoria was wearing off. "What? Why?" "Because I have no way of communicating to all these people how thankful I am. Like I'm trapped. The language doesn't allow for an expression of gratitude that big." I'm guessing everyone on my production, to varying degrees, felt ignored and undervalued at various points of the shoot. It's the nature of the beast. I asked for the world from each of you, and was too busy to say thank you. Friends, know that I knew you then, in each of those moments, as I dashed from issue to issue, trying to keep the ship going. It's because of you that it all stayed afloat. Sometimes the words will just slip out of my mouth. Is it the collective buzzing hum of energy, speaking through me? "Thanks, everyone," I yelled out as everyone got off the 36 at Fifth and Jackson. I often say that. But then I spontaneously added, "love y'all!"

A teenage girl sitting nearby asked her friend: "did he just say 'love y'all?'" "I think he did!" They watched me the way you watch something strange and new, something you maybe want to learn from and appropriate. You know how you pay more attention to the way something looks when you know you''ll be drawing it? I pretend not to notice, doing my best to be myself. I greet a familiar wheelchair passenger with glee, complimenting his new hat and asking where his toy fishes went. Across the street a voice hollers out my name, and I yell a hello back at Edye, on her way to work. Moving along, there's a Somali face I know ("Dealer One" from this post) waiting on the other side, and we howl pleasantries at each other until the light turns green. "Don't mind me," I say to my captive audience. "Just sayin' hey to my buddies!" "I expect a shout-out next time!" a young man quips, and we get to talking. Shortly after the two girls leave, all smiles, excited by all this strange new behavior. We're at Third and Pike. "Let me pull forward for you," I tell Mr. Wheelchair, rolling up to the front of the zone to make room for those poor buses behind me. As we roll forward I realize I'm keeping pace with a familiar sprightly blob of green hair, paralleling me on the sidewalk- she was on my bus earlier in the day. We make eye contact and I yell through the opening doors about how she needs to have a good weekend, and that her hair is great. Sometimes there's a goodwill that will simply do nothing else but burst out of you. That doesn't count as flirting, does it? Mr. Wheelchair, an older first-generation man from a country I can't place, says with a clipped accent and lively grin, "you like the hair, or you like the girl?" We chuckle each other off of Third Avenue, my mock protestations falling on deaf and laughing ears. It'll take too long to explain that this is something similar, but deeper, richer, more expansive. That's okay though. A street lady in a soiled blanket and pigtails ambling across Third notices me, exclaiming, "hey! I was just thinking about you!" And on and on.... I still remember one of my first meetings with a prospective producer. The year was 2009, and I was just out of college. Seattle still made narrative features in those days. The man wore a stetson which he didn't take off, and he was at least three times my age. You wanted to dislike him, but you couldn't. He was patient with me.

"This is the amount of people who want to make a movie," he said, leaning back in his chair, spreading his arms as wide as he could to indicate the large quantity. Then he halved the distance. "This is the amount of people who finish writing a screenplay." Half again, his arms coming closer: "here's the amount of guys who actually go into production and shoot some footage." Again, half the amount, as he continued: "here's how many make it through production." I saw his point, but he wasn't done. "Here's the percentage of that group that makes it into post and actually does something with all that footage they got." He then leaned forward. He held up just two fingers now, an infinitesimal millimeter apart. "And here, here is the amount of people who actually finish making a movie." He paused for effect. "Finish your films, Nathan. People will remember that. If you have actual finished products under your belt, you've got something most of your competition can't even come close to." I didn't end up working with him, but he lit a fire in me that hasn't gone out since. I've completed each film I've set out to make. The latest one, Men I Trust, is complex given its budget, and the Sisyphean effort required to survive and sustain this big little movie over the recent months– financially, creatively, psychologically, logistically– cannot be overstated. Preproduction and production are the hard part. Once you have the footage, you can pump the brakes all you like, but until then, you have no idea if you've got a movie. You don't have a movie until the last minute of the last day of shooting– and even then, post remains a question mark. But as exec producer Kevin Cook reassured me, you take it one piece at a time. You breathe, reminding yourself: All great things are predicated on a maybe. We wrapped production Sunday at 1pm. My first reaction was to continue the habit I'd formed: keep worrying! Look for problems, try to fix stuff, diplomatically guide this orchestra to do their best… but there was nothing left to worry about. Could it be true? How did we get here? The only reason this beast made the finish line was because we managed to assemble one seriously crack team of ace professionals. If even one of them– camera operator, boom, supporting actor– bailed on us, we wouldn't have a movie. That's how fragile filmmaking is. It's not like writing or photography. One lazy apple will ruin weeks of dozens of people's memorizing, assembling, scouting, performing, investing… but these were the non-bailers. They showed up in the morning, before call time. I did everything within my means to make the experience satisfying for them, but it's to their credit they came. Our guys were wildly overqualified. I don't just mean they all know Lynn Shelton; that goes without saying. Kevin Cook worked on Transformers 4, Z Nation and Captain Fantastic, and is trained in everything from method acting to gaffing to production management. Niall James, our gaffer, worked on Fifty Shades of Grey and the new Twin Peaks. Steadicam operator Daniel Mimura has 50-plus IMDb credits and if something's been shot here in Seattle using steadi, you can bet he operated on it. These people are rock stars. Actors Eleanor Moseley and Martyn G. Krouse don't just have significant film roles under their belt, but also thriving stage careers: witness Eleanor chewing subtle scenery in lead roles in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, Death of a Salesman, and The Lion in Winter… all within the last year; or Martyn mopping the floor in recent productions of Slaughterhouse-Five, Othello, and Richard II. You may know Meagan Karimi-Nasir from The Scottish Play and Glitch, or Katherine Grant-Suttie from Portlandia and others. Our media manager had two films playing at SXSW while we were shooting; our AC is a director in his own right; the list goes on, even down to our smallest positions. Our PAs are engineers and lawyers, for heaven's sake. They're administrative supervisors and corporate HR wizards. Our crafty has two degrees. Nobody was grabbed off the street for this production. You may wonder why such levels of talent were assembled for a short. I say, why not use a boulder to crush an ant? It works. Why not use $20,000 cameras on a tiny short, if you are able? I see no reason not to do our absolute best. What this group all had in common was an understanding not just of passion projects (you can bet I couldn't afford to finance them the way the corporate giants can), but of craft. Kevin and I picked these people because they were solid, respected craftspeople who do good work because they like to. Because they know how to, and because doing good work with good people is about as great as filmmaking can get. These guys like getting paid like anyone else, but that wasn't why they were here; they also like working on projects they care about, and I couldn't be more honored they found this one of even the smallest interest. It's about showing up, and giving it your all for the person next to you. You may wonder when watching awards shows why the winners always make boring speeches where they just thank a bunch of people you've never heard of. You have to understand: when you receive an accolade implying that you alone brought something amazing to a film, with no assistance, it feels absolutely ridiculous. It wasn't you! It was everyone else there, the whole cast and crew, who made it great. It was because of that group who believed, who cared, who made it a well-oiled machine. To the non-bailers. -- I'm not done thanking people– click here for more on our production! What a pleasant sensation, to come back to the textured urban haunts of South Seattle and be greeted with welcome, as if a returning friend. I've been scattered in my work schedule and absent entirely for the past week, focusing every iota of my attention on my film (I'm this close to being done with shooting; cross your your fingers for me for sunshine on Sunday!). Film directing is the hardest thing I know how to do, and therefore I must do it. I love doing it. It may be the only gig I like more than driving wonky bus routes through questionable neighborhoods at all hours of the dark night....

Here I was now, off for the evening and walking towards my midnight bus home. A figure stood in the gloom. He called out to his companion, pointing at me, a coach's sporting yell: "That's the best bus driver, right there!" "Ha! I'm not that great!" I laugh-yelled in reply. He further elucidated his claim to his friend, and I began to notice other faces in the dark. These are souls I recognize, I thought, on more than one level. They were relatives in sensation, if not blood; I felt the textures of their lives as my own, the workaday grit and rhythm of service job life. These were the hands that knew the takeout restaurant kitchen sinks, the loading dock garage handles, the construction gloves that grow to know the shape of your fingers. In spending time in a wide latitude of different status circles, I've noticed a problem the very rich and the very poor share in exactly the same capacity. Both groups have to contend, in nearly every interaction they have, with preconceived notions of who they are based on their income. I know wealthy white landowners who overflow with compassion, self-awareness, and a desire to contribute and understand others with genuine empathy, just as much as I know destitute people of color who are educated, selfless, and concerned with ethics and the advancement of society at large. And yet, these folks tend not to get evaluated as such. Abraham Lincoln comes to mind: "I don't like that man. I must not know him very well!" Tonight, however, there's nobody around but us service folk. In a way I hope one day works amongst everyone, we all get each other here. I'm in the Fifth and Jackson plaza, and a gaggle of passengers for different south-pointing routes is loitering about. "Heyy," I say to the middle-aged Chinese man seated on a concrete bench. He's rail thin and doesn't speak English, and tonight waits with one sock-clad foot out of his shoe, maybe resting from a standing job. We fistpound. I can tell the gesture is culturally unusual for him, but he grins at my youthful enthusiasm. Wonder if he has kids. A voice to my left: "Heyy, are you driving the 7 tonight?" "No, I was earlier, I just got off! I'll see ya tomorrow!!" I turned away with a grin and walked right into another man, a chubby friend who sleeps on the Night Owls. We spoke briefly about how I've been away from the bus of late. "Even if I pick something else for a while I always come back around," I said. "I'll be around. They're not gonna fire me, right? Fingers crossed!" "Oh they better not, Nathan! You're one of the best bus drivers around!" He knew my name. How did he know my name? To hear the compliments, this camaraderie in the midnight hour on foot, exposed here at this legendary intersection, engendered a feeling I can hardly describe. The interactions were brief, lasting seconds, but they represented connections I've been building for years. Season after season of smiles and small talk are the seeds of this, now, the sensation of a warm embrace in a place that's supposed to be dangerous. An invisible exhilarating outdoor cocoon. Maybe that's why I don't wear a jacket to work. I have many homes, and am as anxious to return to a film set as anyone else; but there's something special about this home, the great urban experiment I've been conducting for nigh eleven years now, whereupon the forgotten flotsam and jetsam of America behave at their best and their worst, but as ever offer their love toward me, their respect and acceptance… with no agenda whatsoever. They love, expecting nothing in return. I can learn from that. |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed