|

Two years ago today I posted the first of these stories, which now number in the hundreds and stem from seven years of bus driving. The story was from a page in a journal which I never intended to share, but there was something about the exchange I very much wanted to preserve. The feeling of joy I knew in those moments was real, and perhaps by writing that paragraph down I might more easily recall an echo of the sensation.

Once again, thanks to the good people– that would be you, Erin Lodi and Michelle Dirkse and Virginia Eader, among others– who urged me to share these stories instead of holing them up, and giving me the push for this blog to become what it has! And a further thanks to Owen Pickford and Ben Schiendelman for inviting me into the fold of The Urbanist, bringing my stories to an ever-growing audience. Bus driving is a whirlwind. It's the feeling of dipping one's feet into a myriad different worlds, watching and taking part in so many lives and spaces, finding new ways to consider and grow and learn. Here is a collection of days, in celebration of the blogversary, and in an attempt to offer up the experience of multitudes we operators get in just several hours... but most of all I offer the following as a celebration of the people. The blog is ultimately not about me, but about the folks, about how we interact, about ways of thinking. -- Rainier at Walker Street, by the Center Park housing facilities and the 2100 building. A runner sprints up the bus, teenage Latino with aviators and camo pants, slick, he's streaking through time to make it, but wait; he pauses on the second step, body like a dancer, agile, hopping back off the coach to blow out pot smoke before boarding. He stubs out his joint on the cement, and I'm laughing, thanking him for doing that. The eyebrows above the shades smile, his easy grin revealing two rows of small and friendly teeth. A dark-skinned immigrant man leaves quietly. Does he speak English? Is his world close to mine? Yes. In his hand is a book by the recently deceased Maya Angelou. A butch girl and her lady, kissing under the orange sodium lamps at Seneca, bodies held tightly, close together. A man in a wife beater, slapping back at a man attacking him, two men who seem to know each other, fighting amongst the new landscaping on Maynard Avenue, their shouts muffled by the summer leaves. I'm passing by the Iglesia La Luz Del Mundo at Rainier and Oregon, cruising toward the zone at Alaska. There's a Latino woman running, no way will she make it, but she's running anyway, moving pretty quickly. I stop for her, feeling generous tonight. Her smile is oceans wide, breathing heavy and happy, raising the space inside another notch. In my notes I simply described him as "Red G Playa;" a quarterback-sized man dressed in red walking up from the back at Rainier and Andover. He'd been listening to me discuss my love for driving the 7. He adds to the conversation as he steps out, saying, "I always love it when you do the 7." I roll gently down 14th Avenue in Beacon Hill, passing by the International School. A few blocks south and there they are, at home on the overgrown lawn adjacent to the sidewalk– a few Native Americans and others, drunk and high and drifting, behind the tall grass, paraphernalia littered all about them. One of them is Jackie, over there in the wheelchair, and I wave from my passing 36, not sure if I'm making it through their drugged-out haze. In a month or so she'll be in dramatically better shape, on her way to Peters Place on the 7, happy to finally have a roof and a bed. Senior East Asian ladies sitting midway back, spelling out the word Safeway together in english. Some giggling is involved. Phil, always in the corner of my eye, the guy just shows up everywhere and nowhere, a younger man who panhandles near Pike Place. He showed me photos of his childhood days once. Today he squawks to get my attention, practically a bird call, and we wave large. Arana Wang, local artist, is on the sidewalk. "Arana Wang??" I call out. Yes, it is her! We hug and chat for a red light. Myself and a man on the 10, discussing the biography of Douglas Adams, author of the Hitchhiker's Guide series. Adams was a drunk and died young, in his fifties. We're discussing the authorship controversies of the closing book in the series. Anna B on the sidewalk, out of nowhere, another good friend at the 70 bus stop, smiling that smile! Evocative and fresh; imagine the Mona Lisa a few seconds later. Hers is a gaze which has seen many things, but stills revels in the beauty of small moments. "Playing Tetris" on the 36– that is, trying to figure out ways of arranging passengers and their walkers, bags, and wheelchairs such that we can all fit in. I'm standing there with my chin on my hand, looking at a wheelchair and some luggage, doing some mental calculations. I'd hauled the suitcase up the stairs, joking, "this thing weighs more than I do!" The man in the wheelchair has a sleek, terrific-looking new vehicle, called the Luggie, I learn. It looks to be the Lexus of mobility devices. A lady on the 120: "You're a hero to the planet and the people, every day!" A man on the 120: "I like the way you drive, bro. 'Ppreciate it." A thoughtful hipster on the 70, discussing a band he used to be in, Meese, and the perils of working in the entertainment industry. We share horror stories of living in Hollywood. With someone else I expound on the long-lasting nature of the trolleys. An Islamic family in traditional dress is asking me questions. I'm explaining where to get an Orca card, inwardly marveling at their wonderful faces, so many bright eyes ready to smile. 11:42 at night on Capitol Hill, and things are pulsing. A full house this evening, lively and ready for the scene. I'm turning onto Pine on an outbound 49, waiting for the people crossing in the crosswalk. Two of them, a couple, suddenly become animated: it's Kristina and Adam, dear friends, out on the town on Friday night! What are the odds? I open the doors and beam at them. Kristina asks if they can hop on for a moment. Of course they can. I'm overjoyed. We ride several blocks together, chatting up the space, sculpting new sides to our respective evenings, connections and smiles livening up the space even further. Several minutes after they leave a woman will come forward with a cupcake, offered by way of thanks for the joyous ride. Me, walking by myself, basking in the sunshine at Volunteer Park on a layover, sitting under a tree for nine precious minutes. "Shit is deterioratin'," said a man walking by to his lady. I can't agree.

2 Comments

Here we have a transcription of an interview with yours truly– conducted by the great Erica Weiland, a local writer, editor and media manager, for whose time and enthusiasm I am grateful. The transcript is an unexpurgated record of a huge conversation; this is merely part one. I thought you might find it interesting.

An Interview with Nathan Vass – Part 1 Rainier and Henderson, the bottom of the Valley, deep in the living night. We're in the nerve center for gun crimes and drug distribution– the former up 150 percent in Rainier Beach within the past year. While the recent SPU shooting drew national attention, activity in Rainier Valley tends to go unreported. Locals know the numbers– about 50 shootings, 25 of them documented, 12 murders, and nine assaults since mid-April: it's summertime in the 'hood. Only out here do I hear folks dread the onset of summer.

We in Seattle are fortunate in that we can get worked up over such small numbers. My hometown of Los Angeles is happy to have gone from 299 murders to just 251 in only a year, with per capita crime the lowest it's been in five decades. While one incident is too many, and the loss of a single life undeniably tragic, I might suggest it is not harmful to maintain perspective. Isolated incidents are not always indicative of trends. While we're reading articles with titles like Another Day, Another South-End Shooting, let us try to recall that news reporting is selective. Far from making us "more aware," a notion which would be comical were it not so patently wrongheaded, wallowing in crime news in fact builds a view of our surroundings which is not just skewed, but incorrect. Only from a mindset of staggering privilege and reactionary, ignorant fear could we do ourselves the injustice of failing to see the modern miracle which happens in Seattle's greater metropolitan area every day: each night, nearly all three million souls make it home, completely unscathed. I remember living in LA and watching car accidents happen in front of me while waiting for the bus home. This was a regular occurence. The idea that most of these other cars– in fact, practically all of them– would not get into accidents tonight seemed so unlikely. How was it even possible? Would LA's twelve million people really follow those colored lights and stripes on the road well enough that ninety-nine percent and change would actually make it home without their cars touching any other cars? It seemed impossible. Impossible! But it happened, every night, and the saddest thing was that nobody noticed. They were part of a truly unbelievable, physics-defying miracle, and no one cared. Now is also a good time to point out that crime in our great city, however we're looking at it, is either declining sharply, flat, or slowly declining. Seattle continues its steady decrease in overall crime since 2000, and has 32 percent less crime now than then. Homicides are down by 12 percent and assaults by ten in the last year; the numbers are more dramatic if we go back further. It's worth relinking Dominic Holden's detailed writeup from a year ago, Crime is Not Actually Spiking Downtown, and situating it in the larger context of our tendency to think crime is up when it's just the reporting that's proliferated: violent crime in the US has been declining steadily since the 1990s, and the LA Times article sums up reactions to that fact succinctly: Gun Crime Has Plunged, But Americans Think it's Up.* All of which is to say, let us try to keep our outlook in proportion. Float above the madness and consider the aerial view. If you read the above-linked Rainier Beach crime article, please also read More to Rainier Beach Than Crime, Violence and Rainier Beach: A Beautiful Safe Place for Youth. Take in the beauty and stories of your Seattleite neighbors, those vibrant faces of all colors, hopes, and commonalities. Recognize the similarities in your dreams. There is no Other. Back to Rainier and Henderson, where I pulled up to the stop at about 10:50pm. Open the doors with a smile. A few thugs get on, tall and hulking, heavy in jackets and swagger. These are the hard types, connected, the men the teenagers wish they were. I greet each one with eye contact and some variation of "hey, how's it goin'?" They appreciate my friendly gaze, equal-handed respect and complete lack of fear. The second shakes my hand after I oblige his imploration for a transfer. The third steps on with a "hey man, I'm tryna go ta work." He shows me a couple faded white plastic cards, incomprehensible to me. It's eleven o'clock at night in Rainier Beach. Going to work? Really? It seemed like a ridiculous excuse, if that's what it was. Was he trying to "scam the system?" Nope. I let him ride in any event, and soon saw him halfway down the bus, still standing, removing his coat and other outerwear and suiting up, as it were. He was putting on thick undershirts and some sort of waterproof coverall. Afterwards he put the jacket back on. "Gettin' all dressed up for the nighttime!" I said. "Yup, gettin' ready for work." "Rockin' the night shift!" "Yeah, I do the pressure wash, at Safeco. S'pposed ta be there at ten, but don't usually start washing til eleven, so I'll still be early. We wash all the seats." "That sounds cool. Getting to be out there in the stadium, nobody else around." "Yeah, iss good." "Been doin' it a long time?" "Yeah." "Good to have a job like that, something interesting, different," "Yeah. It's fun." "Awesome." There is no other, indeed. I'm so glad I gave him the benefit of the doubt. There are people I know who wouldn't have. I attended a play some years ago in the Central District's Washington Hall. A ladyfriend was performing, and the show revolved around the subtle mistreatment and unintended subjugation of women in college environments. The playwright was on hand for a Q&A session afterwards. Somebody behind me, a middle-aged man, prompted him by saying, "we're all sitting here, in a playhouse in the Central District, and we're probably all left-leaning liberal people, who already agree with the excellent points made by your play. I don't think any of us here believe in sidelining women... I guess what I'm trying to say is, this play expands our understanding, but we already agree with its main points. What can we do to change the minds of people who don't? How do you get this to change the minds of an audience in the backwoods of Arkansas...?" The playwright looked at the floor for a while. His legs were crossed in front of him, and his hands were clasped around his knees. He picked at the cloth of his pants and finally said, "I'm really glad you asked that. Because I think about that question all the time. What you're basically asking is, 'how do you change the world?' And my answer is, you don't. You change the person next to you. And you do that by being yourself. You don't even try to change them. You talk to them, you... whatever. Just be yourself. That's how you change the world. Be something they can see and think about, and maybe they'll change their way of thinking a little bit. It happens not on a mass scale, but on a human scale." --- *Even if crime is low, it's still worth lowering; how do you lower crime? Community Policing is the new watchword. “A community that watches after each other,” [LA Police Chief Charlie] Beck explains. More from the LA article linked above: "Beck credited community policing for the 17.6 percent drop last year in gang-related crime in Los Angeles. He said the LAPD doesn’t only rely on policing and enforcement, but works with interventionists to control rumors and prevent retaliations. 'Sometimes over policing makes gang identity stronger,' he said. 'You have to watch how you police it. We have just the right prescription in Los Angeles right now.'" Not all of the conversations I have on the bus are the gleeful bastardizations of syntax which I often record– and which are no less legitimate uses of the English language, mind you!* Here's a sample of a perfectly grammatically acceptable discourse.

"So what's playing at the Benaroya tonight?" I ask as we approach Union. He, a slightly older man in a crisp black three-piece, had asked earlier for Seattle Symphony. "Rachmaninoff." "Oh, excellent!" "Two symphonies, I don't know them too well. Hey, you're the friendliest bus driver I think I've ever seen." "Oh, thanks!" "I especially appreciate the announcement of the upcoming stop after the next stop." Referring to how I try to keep folks informed when we're in the CBD in skip-stop heaven, as in, "the stop after this one is James." "Oh, thanks! It's great to get the feedback. Rachmaninoff, excellent! I'm not as familiar with his work as with other composers." "Did you ever see that movie Somewhere in Time, with Christopher Reeve, from the eighties?" "Not for ages, but yes!" "Well, the main theme for that is from a Rachmaninoff symphony." "Oh, terrific!" "But yeah, I dont know these symphonies too well. These were free tickets!" "Well, there you go! Not a bad way to pass the time!" "Exactly!" Chuckling. "Yeah, the last time I was here was for the Ninth symphony, Beethoven. Obviously fantastic," I say, throwing my hand in the air, as if giving up at the act of trying to succinctly express how great it was. I was raised on classical music. To me, it's strange to consider it as a genre, as we consider folk or hip-hop; it's so much infinitely larger. Classical's been around for a thousand years. Popular music's existed for a mere sixty or so. The vast, overwhelming percentage of existing music is classical music, and some of it is absolutely worth your time. As Grand Puba says in the Tupac Shakur tune, "I wouldn't be here today, if the old school hadn't paved the way!" "Oh, it's such a great place." I forget which of us said this. "It is," the other said. We were both basking in the shared warmth of loving the same thing. "I have season tickets!" he said. "Perfect! Well, hope it's a great evening!" "Thanks! You enjoy the rest of your shift." The color of his tone was sincere, and the last sentence carried with it the implication that my time tonight on the road was as valuable as his inside the Symphony hall, if not moreso. What I loved about the exchange was the undercurrent drifting through all of it, which I felt all the more strongly because it remained unspoken: he, the man wearing a suit probably worth my entire paycheck, spoke to me with not a trace of condescension. A good day's work and the ability to appreciate culture existed for him on a spectrum which included not just people like him in the narrow sense, but myself and everyone else. A girlfriend once asked me why I like the LSBW (read the post about her or watch my speech on this legendary passenger if you haven't already). I remember looking out the window, thinking for a moment before saying, "because I have so much more in common with her than I don't have in common." "Really?" she said, listening. I thought so. Just a few changes in brain chemistry and life circumstances were all that separated us. Mr. Rachmaninoff, above– hopefully he doesn't mind my calling him that– seemed to have a similar view, and it felt good to be on the receiving end of that. *"The myth that non-standard dialects of English are grammatically deficient is widespread," writes linguist Steven Pinker. We can all grasp that language evolves through slang and progresses to new places through colloquial use, but additionally, dialects such as the much-maligned Black English Vernacular (BEV) have just as constructed a framework as the more familiar Standard American English (or SAE, itself a derivation of British English). From Chapter 2 of Pinker's The Language Instinct: "Where SAE uses there as a meaningless dummy subject for the copula, BEV uses it (compare SAE's There's really a God with BEV's It's really a God). Larry's negative concord (You ain't goin' to no heaven) is seen in many languages, such as French (ne...pas). BEV allows its speakers the option of deleting copulas (If you bad); this is not laziness but a systematic rule that is virtually identical to the contraction rule in SAE that reduces He is to He's, You are to You're.... In both dialects, be can erode only in certain kinds of sentences." BEV does not allow Yes he is! to contract to Yes he!, as SAE doesn't allow Who is it? to contract to Who it? Pinker continues, stressing that BEV isn't all about contraction: "BEV speakers use the full forms of certain auxiliaries (I have seen), whereas SAE speakers usually contract them (I've seen)." He concludes with a point my friend and I were discussing just the other day: "He be working means that he generally works, perhaps that he has a regular job; He working means only that he is working at the moment that the sentence is uttered. In SAE, He is working fails to make that distinction." You've perhaps seen my photographs of Asia before. I took thousands while there. The act of being alone, traveling alone, with no filter between you and the universe, no companion to direct your thoughts this way or that– this is magical to me. While this set of images might not be as pictorially appreciable as the Asia photos I tend to show at galleries, sometimes it's in these offhand moments and glancing snatches of reality found in the outtakes where you find something truly affecting. They're in the Photography page; hope you enjoy them!

This guy stumbles on like a rock tumbling through an unstoppable river. An imposing physical presence. We're somewhere at the bottom of Rainier Valley. He's clad in a white oversized T-shirt that would be a dress on me, the shirt peeking out from under a puffy black jacket of colossal proportions. He asks if I go to Genessee, pronouncing it "Jensee."

"Absolutely, yeah. And hey, I'd appreciate it if you kept that closed." I'm gesturing at his paper bag, which contains a bottle of you know what- something other than pink lemonade! "Oh, it is." "Thanks man, I appreciate you." "No probl'm." At Genessee, he mosies up , leaning forward, peering into the unknown distance. "I think I go one more." "Oh no worries," I say. "We'll see if somebody else wants this [bus stop]. Thanks for tellin' me." "Sorry 'bout tha,'" he says after watching me greet somebody getting on. He's treading lightly, politely. I see him in the mirror, and in my periphery. Quarterback body, gold necklace, and a trim goatee, hints of jailhouse tats peeking out above the shirt. "Oh, it's all good. So kinda right up there, by Safeway?" "Yeah. Hey, uh, thank you, for doin,' for bein,'" Hardcore manliness stops him short from an easy finish to the sentence, but the sentiment is no less real. I know what he means. "Oh my pleasure man, it's no worries. I like bein' out here." "Thanks, dude." He feels more comfortable now, more revealing: "I'm new here. Jus' come up from California." "Oh wha' part of California?" "LA." "Dude, right on!" I exclaim, preempting the next question all Angelinos ask each other, which is, 'what part of LA?' "I'm from LA too, I'm from South Gate!" To this his eyes light up, all pretense and vulnerability falling away: "WHAAAAA, no way! That's just up from me, I'm from Lynwood!" "No waaaayyy! Right there!" "Oh, you right over there. You in it." This happens more often than one might imagine. On the 70 I took a couple toward the airport and discovered we all once lived on Firestone Boulevard in Downey. Recently on the 44 a woman overheard me discussing LA, and revealed that she'd come up from San Diego in '96. "There's a lot of us Californians taking refuge up here," I marveled. "There are," she responded. "Some folks don't like it, us bringin' our LA ways up here..." "They'll just have to deal!" Strangers in a strange land, no longer strangers. My friend looking for Genessee leans back in his chair in a way he couldn't before. Relaxed now. He'd felt comfortable enough in my space to share that vulnerability, that he was new here, and the payoff was worth it. We pass under the dark trees at Byron, making our own sunshine. He seems particularly glad that we come from the same mad realm of South Central. The Jungle, as it's called. Whatever challenges he's up to here in the Valley, they'll be easy compared to life in the Jungle, and he knows I know that intimately. "Out there, you know how they do," "Oh yeah!" We're in fistpound handshake heaven. "Be safe!" we say to each other at the end of the ride. It is not a pleasantry for us, but rather a genuine urging, a belief that the other's life is worth some extra caution. It's late, and dark, but we're both glowing. Josh is in his late teens, African-American and something else, tall but not too tall. In our youth we sometimes oscillate between dialects, particularly when we have multiple backgrounds. Regional dialects and generational slang can surface on will for people of any age. Lyndon Johnson would speak differently based on who was in front of him, sometimes employing the heavy Texan twang, other times keeping things to a more civilized drawl. When people chat with me, especially younger folks, they're sometimes not quite sure how formally to style their language. I like when they start out hesitantly but gradually open up, easing back into their normal self. I find myself doing the same.

Josh didn't bother with any of that, though. He seemed comfortable from the get-go. He first accosted me with: "Yo, how old are you? "Fifteen," I deadpanned, checking my blind spots. "Naaaaw!" We did the conversation where we discover my real age, working through the motions of a well-worn exchange, still enjoyable every time. This time I steered it in the direction of jobs. He asks how long I've been at it, when I started, and so on. "Pay is good?" "Oh, man." Laughter. "It is not bad." I remember my first job at the library, where I was thrilled to receive seven dollars and seventy-eight cents– over and over, with each new hour! "I'm never gonna complain about this job. Trying to justify that paycheck, you know?" "Ah heard dat!" "Where you work at?" "I used to work the shipyards, getting' paid twenty-seven an hour." "Wow, hey. Somebody's getting' paid." "Well, used to. Hey, you know them e-cigarrettes, the vapor ones?" "Yeah yeah, the electronic things," "Are those allowed inside the bus?" "That's a good ques-, actually they just changed that. I was talkin' about that with someone earlier today. It was legal, but now they're changing it so they're allowed only where real cigarettes is also allowed. How come, somebody givin' you beef?" "Naw, I's jus' curious, couple drivers sayin' different stuff about the rules," "Hopefully they just ask you to put it away. You know, there's so many rules these days. You know how older folks talk about earlier times when there wasn't as many regulations?" "Yeah," "I wanna get back to that time." "I'm down with Metro, man." "You and me both! So, working' in the shipyards. That's work." "Yeah, I used to do welding-" "Whoa-" "-but I hadta get outta there, man, too many layoffs. Cause I got kids, bro." "Okay, so now you lookin' for something a little more stable." "Well, I got one now, I'm at the dispensary." "Oh that's right, right there off Aurora. "My uncle is a boss there." "There you go, helping each other out! Symbiotic relationship!" "Yup yup! Well, actually iss my girlfriend's uncle." "Oh right on, man. Shoot. Don't break up wit' her!" "Aw no way, dude, never. She pregnant with my baby." "That's a beautiful thing. Makin' it work." "For sure! You always on this one?" "Same time same place, every day!" "Coo'. I see you around!" "You too!" As he bounced off at Bell Street, gliding over to his next bus, I realized he was the youngster who profanely but wisely counseled the agitated fellow described here. There are times when you realize all the acting, the facades of clothes and cool, are merely a vernacular for youngsters to cope with the impossible business of being an adolescent in the modern age. You realize, as I did listening to Josh's tone as he mentioned his girlfriend and baby, that there is in fact just as much depth of caring in there, and that over time the facades will peel away like so much dead snakeskin, and they'll blossom into the good people they always were. Moments like that make me believe in the future. Let's see, where were we. Continuing our exploration of what trolley buses are, from the previous post~ All other trolley systems in the US have backup motors for dewirements or reroutes, and Metro's new fleet* will as well. But the fact that we have to drive without them now makes Seattle's trolley operators, in my humble estimation, the most skilled. You just can't mess up. The more backup features your vehicle has, the less you have to pay attention. This is one reason why, statistically, expensive luxury vehicles get into so many accidents. They're too safe. So how exactly do these things work? Let's get technical for a moment: You may have noticed from riding trolleys that the operator will often slow down in completely random areas like the middle of intersections, often while a short "beep" sound is heard. Is the driver daydreaming about parking there and walking off to lunch? Is he under the influence? No, he's just being a pro. The poles are passing through switches in the wire, called "special work." Special work is where lanes of wire intersect– the wire for buses on eastbound Pike crossing the wire for buses on northbound Third, for instance. The easiest way to lose poles is by driving too quickly through the special work- slowing down for them actually saves you time. The "beep" noise you hear if you're sitting at the front is the bus passing through a deadspot. For the duration of the time that beep noise is happening, there's no power in the overhead. Just as you can't splice two electrical wires of extension cords together, the sections where live wires intersect need to have "deadspots–" a section of as little as six inches or as much as several feet where one of the lanes of wire is dead, so the other can be live. You can identify the deadspots because they look like big suitcase handles above the wire, as seen below.** You have to slow down for a deadspot, or else you might blow your poles by driving the shoes too quickly through the resistance the subtle changes in surface metal the deadspot provides. But you also can't slow down too much, or else you might come to a stop and subsequently get stuck, now forced into the embarrassing business of having to go out and figure out what to do with the poles.*** Nor can you just power through it with your foot on the floor- that arcs the power, causing the bus to shudder, and will sometime kills your vehicle. Not wise, especially on the steep hills. How does the driver know where a deadspot is? You have to memorize them. Some operators get a feel for the rhythm of the intersections, remembering they need to slow down here or there. I and other drivers take a more fastidious approach. I like having landmarks. I want to know, down to the inch, where each deadspot is. Thus, I'll memorize landmarks for where the front of the bus as we pass through each deadspot. This mailbox, for example, that birch tree, or the "open" sign in the Vietnamese market– right as the front doors pass by those, I hear the beep. Perfect. Only one of the lanes of wire in a crossing of wires has a deadspot. The other remains live. In the planning of the trolley network, the lane of the wire with the live current generally goes to the direction of travel that needs it most in that moment, perhaps because of an incline or a turn. For example, the left turn from southbound Third onto eastbound James, pictured below, has no deadspots, while the northbound wire on Third there does; the turning bus needs the live wire more because he's about to go up an incline. Makes sense (On the other hand, we won't talk about that left turn from Madison onto 15th!). How do buses switch from one lane of wire to another? In Seattle there are two ways of doing this, specific to the way each switch is built. Often you put on your turn signal, and this sends a radio signal to the Fahslabend switch in the wire, causing the metal tracks to shift, as on a railroad. You can hear a metallic "click" when this happens. Many operators drive with their window open so they hear everything going on upstairs and can more easily navigate the wire. It's also easier to wave to your compatriots driving across the street! Atlantic's (the trolley base) drivers are more tightly knit, as we need to work together more intimately then other drivers do. There's also the shared camaraderie of doing what is variously considered the best, hardest, worst, greatest and toughest work. As your poles pass through the switched track, the tracks reset so the next coach passing through isn't also forced onto the wire you chose. This is the case on Jackson westbound when turning onto northbound 4th. If you didn't hear the click, it's time to go out and move the poles.****  The other type of switch is called a Directional, or Selectric. You're northbound on Third, turning right on Cedar, because you're a 3 or 4. While doing so, your bus will be at a 45-degree angle to the roadway in the middle of the turn, and this angle will cause your poles to trigger two contact points in the wire overhead. At left, the bus's poles would be traveling from lower left upwards; note the two small rectangular strips with tiny wires emanating from them and going to the actual switch. Those are the contact points. Because your bus would be at an angle during the turn, your two poles will touch those contact points (one on each actual wire) simultaneously, the wire will realize you're turning, and you'll hear that metallic click again, right as your bus passes through the switch. Once again, it resets for that route 2 behind you, who wants to go straight up Third without turning.***** All of this might sound baffling or needlessly confusing, but on the road one finds a pleasing rhythm that I consider relaxing. Basically, I love this stuff. There's no engine, so the vehicle doesn't vibrate or rumble. There's just that gentle whir of the motor and accompanying electric hum. In the resulting quiet you hear more– people shuffling or talking, the sounds of life going by inside and out. You can't rush. It's not an express, after all, it's the neighborhood trolley route, picking up and dropping off and cycling that lift like nobody's business. You get into the rhythm of things. I tell people they'll love trolleys if they're a workaholic and really patient. It's possible to go for months without losing poles.****** You find a cadence, memorizing all the deadspots, gently playing with the brake and power, making each ride smoother than the last. Those of you who are stickshift drivers and like driving manually can perhaps sympathize. It takes more thought, but that's part of the fun of it. The system and concepts of trolleys were developed many decades ago, but sometimes you really don't need to fix things that work perfectly. There's no arguing with the fact there isn't a better way of moving a 30-60,000 pound vehicle through Seattle. Trolleys don't have exhaust pipes. They are a zero-emissions vehicle. The electric motors have very few moving parts, and basically last forever. They qualify for fixed-route status and thus receive federal funding. The cost-savings of not having to buy fuel for a vehicle for twenty years is quite literally incalculable. They have more torque and better braking then diesels, are quieter, cleaner, more efficient and last longer. Matters like quietness, air quality, environmental justice, neighborhood character, lower road impacts- these may not be monetarily quantifiable advantages, but they need to be considered as the undeniable and important benefits that they are.******* Aside from their advantages over diesel and hybrid buses, they also surpass streetcars (the latest in politically popular transportation fads) for a number of reasons we would be mindful to remember: they are dramatically cheaper to implement. It's impossible to overstate the price difference– and they offer either comparable or slightly superior results. They are faster than streetcars. Rubber tires have greater traction than steel wheels on steel rails, making braking and the climbing of hills safer. They can maneuver around traffic and blocking incidents where a tram is rigidly forced into a path of travel. We've all been on the South Lake Union Streetcar when a few inches of a car in the way forces it to a standstill. Disabled trolley vehicles can pull off the roadway, whereas a streetcar essentially needs to break down on a side track to avoid blocking. Trolleys can pull to the curb to service zones, eliminating the need to construct islands in the street. Regenerative braking puts electricity back into the grid, conserving power.  They are the nerve center of Metro's bus system. In a network with 223 routes, the fifteen trolley routes carry over a third of all the ridership. If anything, the wire should be expanded. Most of our trolley routes are old streetcar routes, and the longevity of the corridors continues to make them a predictable and trustworthy option for many. You'll notice how some residential streets are wider than others (12th Avenue on north Beacon Hill, as opposed to 14th; 6th Ave W on Queen Anne); that's because they used to be streetcar lines. There was a time when most non-freeway routes in Seattle were on the wire. The old 15/18, routes in West Seattle... we currently have 55 miles of wire, which is great. But Vancouver has over 300. I look forward with hope to a time when moving closer to such things becomes possible, and commend the officials in place today who have encouraged and allowed the current system to be what it is, and who have the vision to see what its future can be.******** Notes:

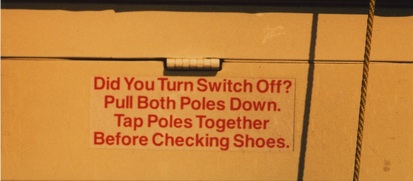

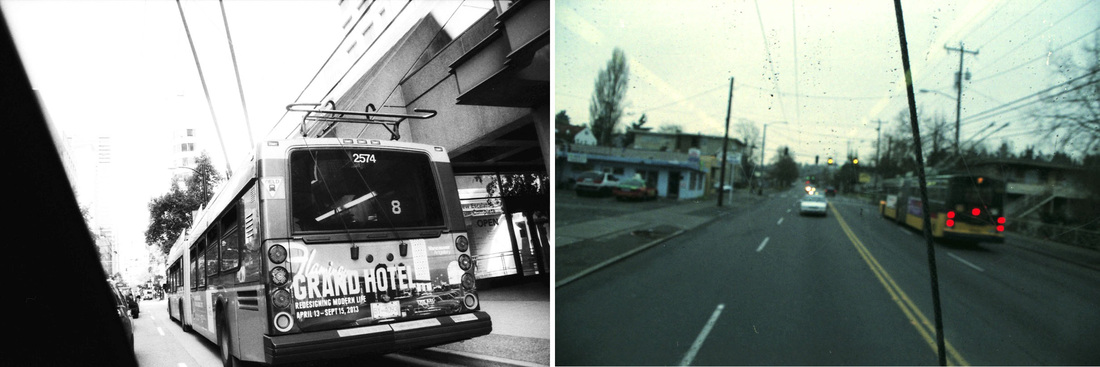

*The new trolleys will be purple! You heard it here first! **Except on Broadway. Those new intersections at Pine, Madison, and Jefferson were subcontracted out to a different company for the streetcar construction, and that overhead wasn't built by Metro. You'll notice the wire looks different, is more fragile, moves the lanes of wire out to different widths than everywhere else in the system, and the deadspots are difficult to identify– just a black covering around the copper above the wire. See how the new wire at 3rd & Denny, built by Metro, is sturdier and results in less dewiring. ***Somehow there is almost always a way out of this situation. Usually there's another lane of wire you can use for a few feet. If the road is narrow enough (for those of us who've gotten stuck on that six-inch sectional insulator deadspot at 15th & John in Capitol Hill), you can use the wire on the other side of the street, so long as one pole is on live wire and the other is on grounding wire. ****The "siding wire" (lane of wire you can pull over onto, so other trolleys can pass on the main wire) on both sides of 5th and Jackson is famously insensitive, and often won't recognize your coach. Those are two switches which could use an upgrade; for now, I find if I slow down to a near-stop the wire will hear my plea. The more often a switch is used, the more reliable it is. *****Vancouver has a third type of switch, called a Power-on-Power-off. They use it instead of our Fahslabend turn-signal-activated switches. Up there, coasting through a switch versus powering through one determines if the wire will be triggered to switch your poles. Coaches are equipped with a toggle switch to do this in circumstances where accelerating through a switch would be unreasonable (going down a steep hill, for instance). ******Having said that: some words for new trolley drivers, if I may be so bold. Don't listen to operators who tell you they never lose their poles. Everyone loses poles sometime. Concentrate instead on giving a smooth ride- it is possible, even in a Breda. Learn the rules for weaving on Third, don't power through deadspots, and definitely don't worry about who's behind you. They were as new as you were once, and if they're impatient, that's their problem. Be the gold standard. Also keep in mind that at the end of the day, not hitting cars and trees is more important than staying on the wire! Aside from the wire, with respect to the higher volume of clientele and the grief they will give you: your job is not to be a human being, but a saint. *******Didn't learn enough about trolleys reading his? Check out the 132-page evaluation done by Metro in 2011, which explains in more detail than I can about why that purchasing new trolleys is an advantageous solution for economical, operational, and quality-of-life reasons. ********What's that snazzy new vehicle in the last image? One of Vancouver, B.C.'s 282 New Flyer trolleys, the gold standard for a trolley system, if I may say so. We're sitting at Third and Seneca northbound on the 3, a trolley bus. The passenger in front asks me what my favorite routes are. "I really love doing the trolleys," I respond. "Oh. I've never been on one of those," he says. I point out that he's sitting on one as we speak. There may be more than one person out there who's not entirely sure what a trolley is, or who has perhaps never ridden one. In the interest of sharing my passion for them, and in particular enlightening our far-flung readers, I'm compelled to offer some information on what exactly trolleys are, and why they're so great. A trolley (or trolley bus, trolley coach, or trackless trolley) is a bus powered by connection to overhead wires. Poles extend from above the coach, connecting the bus to its power source. You're familiar with streetcars and light rail, which only need one overhead wire. Why does a trolley need two? Because with rail the electrical circuit is completed by the metal rails upon which the vehicle travels. Trolley buses, with their rubber tires, have no such metal contact point on the ground and thus need two wires to complete the circuit- one a live wire, the other a grounding (dead) wire. The grounding wire is usually the one closest to the sidewalk. A trolley does not contain an engine or transmission, in the traditional senses of those words; there is simply a series of circuit boards inside the coach which direct power to a single gear. The "gas pedal," called a power pedal, is less like a gas pedal than a rheostat. Like a dimmer on a light bulb, you press it to adjust the amount of current being poured into the gear connecting to the rear axle. If you floor it, you're dumping 750 volts into the rear wheels, and you can fly up the steepest hill in the network– that would be the Queen Anne counterbalance, at 18.5 degrees– without a hitch (James Street is a close second, at 18.3 degrees. Why does the bus go so slowly down these hills? Simply for safety. Trolleys and diesels have a speed limit of 10mph downhill on these segments, to avoid plunging into Puget Sound. Buses weigh at least 30,000 pounds, after all!). Trolleys, like public transportation in general, are much more popular outside the US. Only six cities in North America have a trolley system. In order of size, they are: Vancouver, B.C., Frisco, Seattle, Dayton, Philly, and a couple lines in Boston. Hilly cities benefit most from a trolley network. A trolley's torque is dramatically stronger than any conventional diesel engine, and thus they can handle hills much more easily. You're not shifting gears with an internal combustion engine, waiting around to get up speed– rather, you're just shoving current into that single gear, already flying. The agility with which they can take the hills is pretty astonishing, given how accustomed we are to large things in general always moving slowly. It's also worth pointing out that the added torque and better braking lend themselves to superior performance on flat stretches as well. Why are trolley bus brakes better? Trucks and diesel buses are equipped with engine retarders, which slow down the engine when you're coasting, so the regular air brake, called a service brake, doesn't have to do all the work of stopping such a huge vehicle. Trolley buses have "Dynamic Brakes," which are a step up from retarders; they perform the same end function, but rather than slowing down the engine, they actually reverse the thrust of the motor. The generator circuits of the traction motor are loaded down with electrical resistance, resisting the rotation of the generators and thereby slowing down the rotation of the wheels. Reverse thrusters are used to slow down airplanes. Is that better than a normal engine retarder and service brake? Abso-friggin-lutely. It also minimizes wear on friction-based braking elements, allowing the service brakes to last longer.  The poles above the bus are spring-loaded and push up against the overhead using springs and air pressure. A small U-shaped shoe with a carbon contact surface ("carbon insert") is what actually touches the wire. The U-shaped shoe pushes up against the wire, which sits inside the 'U.' Electrical current comes from a network of power plants stationed around the city. These are separate from the city's electrical grid– regular power outages don't affect the service. In the old days the poles were made of steel, as seen below, and they flew off all the time. Now they're made of fiberglass, and can stay on the wire with greater flexibility.  Left, you'll notice the slight bend of the white Keipe Elektrik poles currently in use (two coaches, 4110 and 4236, mysteriously appear to still have steel poles; those two are harder to keep on the wire). The length of the poles and ropes behind the coach give you twelve feet of leeway on either side of the wire to maneuver around traffic. Twelve feet is the width of a regular lane, which means you generally have two lanes to work with, but if the wire is carefully positioned, sometimes you can straddle three lanes if you go slowly. Madison between 8th & 5th and 5th Ave North at Republican are examples of this. You might notice drivers staring intently through their mirror at the back window– they're looking at the ropes outside, trying to get a sense of where the poles are above the coach. If the two ropes are vertical, then you're directly beneath of the wire, of course. When they start slanting, you're drifting away. When the ropes look like they're about to touch in the corner of the back window, that's as far out as you can go. The new trolley buses, arriving in 2015, will not have back windows (unheard of with trolleys), and this will make driving them quite a bit more challenging. What happens when you go too far out from under the wire? The poles pop off. Nothing holds them onto the wire except air pressure. It's amazing to me that they don't pop off all the time, after every bump or turn in the road. A fellow named Max Schiemann developed all this in 1901, and he was one smart cookie. The reason there are ropes connecting the tips of the poles to the back of the coach is twofold: firstly, that way you can actually move the poles about without climbing on top of the coach. Secondly, the ropes supply tension. They are spring-loaded as well, and pull downward, although with only a fraction of the upward pressure the poles possess. This counterbalancing downward pull allows for the minimization of the effects of dips and potholes in the road– things that might otherwise throw the poles off. If one of your poles is coming off too often, you might go out and redo the tension on your ropes, which involves pulling out all the rope and re-winding it around the spring-loaded wheels on the back of the bus.  Ever wondered what the phrase at left, printed on the back of every trolley coach, means? Sadly it's not a reference to tap dancing. They're talking about a scenario where you're wanting to inspect the shoes on top of the pole, because perhaps the pole(s) are coming off even though you're driving properly. They're suggesting that you turn the bus off, and then tap the poles together to discharge any spare electric buildup before getting in close proximity to the shoe. All great ideas, though the likelihood of there being any spare charge in the pole is very small once you turn off the coach. When the poles come off, there is no backup system for moving the vehicle. There is no emergency engine. You'd better hope there's wire your poles can reach, or a slope in the roadway for using gravity to drift back under the wire. Usually there is, but the margin for error is tiny. I find this just fantastic. It's totally exhilarating. It forces me to be in the present, and to concentrate. Sometimes on flat ground with no live wire overhead you'll be at a loss for what to do. The temptation is to simply push the bus a few inches and get back on live wire. A 60-foot Breda trolley is heavy, but trolleys are built to roll... is it possible to push a 55,000 vehicle with your bare hands? I won't tell you if I've done so. I'll simply say that I "haven't," since that would of course be breaking the rules! That's part one. Click here for Part Two!

I tend not to throw around the word "epic" lightly. Its usage has changed in the last five years. For some people, it's a word used to describe the number of paper towels you've just bought, or the intensity of people's farts. Even respected film critics use it to describe 90-minute chamber indie dramas. For me, "epic" refers to ancient Greek poetry. It refers to films that approach three hours in length, or books like Zhivago and The Brothers Karamazov. But as many linguists will tell you, language, an ever-changing entity, is defined by how it is used, not by what those high-falutin' types think the rules are. In that spirit, I'm telling you now that I'm working on an epic, massive, gargantuan behemoth of a post (posts plural, actually) exploring what trolleys are. I've discovered that not nearly enough folks know about these lovely vehicles we're lucky enough to have in this city. I hope to put those monstrosities up later this week. For now, let's hear what these two oldsters have to say:

Two older Asian men give me very unexpected responses to my greetings: the first is a fellow at Rainier and Forest. "Hi!" That's me, greeting him. "Hi." "How are you?" "Good how're you?" he says in a thick accent. "Good." "You're very handsome," he says harshly, in a tone of dictatorial approval, without missing a beat. I laugh. The second is a senior at Dearborn. I'm not expecting him to speak English. I greet him anyways, so he feels comfortable. I greet everybody. Tone of voice carries as much meaning as the words themselves. "Good afternoon," I say, expecting silence. "Whassup my brudder!" he replies. |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed