I walked around the Colosseum for thirty minutes before I took a picture.

Part of this was in reaction to everyone else, who rushed quickly up to the edifice, snapped a shot from their selfie stick, and hurried back to their tour bus. "People don't experience life anymore," filmmaker Michael Mann told a panel in LA last year. "They document it."

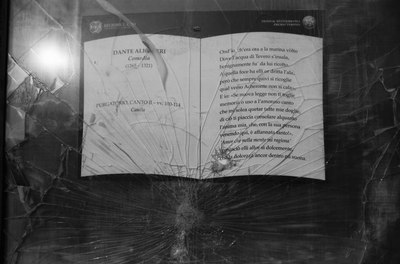

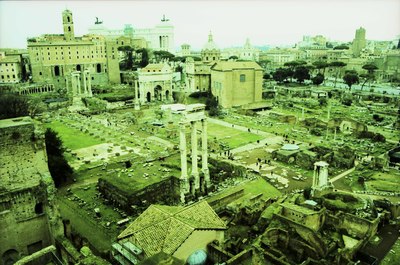

I have not lost my love for life experience, and though the selfie-sticking dashers seem to be in the biggest rush to miss out on possibly the most exciting parts of their lives, I doubt they have either. They're having a good time. But they and I are at cross purposes when it comes to artmaking. I have no interest in proving I was at the Forum or the Diocletian Baths. There isn't a single identifiable portrait of me in any of these places. I know I was there. I also have minimal interest in documenting what these amazing monuments look like. That's been done well by others elsewhere, a hundred times over. Even more pointless is taking the camera inside a museum– what will my photo of Raphael's Madonna of the Goldfinch have on the reproductions made by museum professionals with controlled lighting and unparalleled access to the painting?

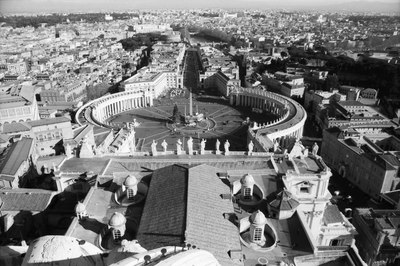

What then do you do? Is it even possible to bring a fresh perspective to a city depicted as often through the ages as Rome?

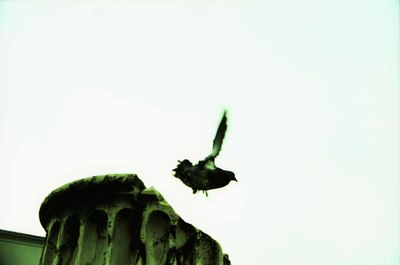

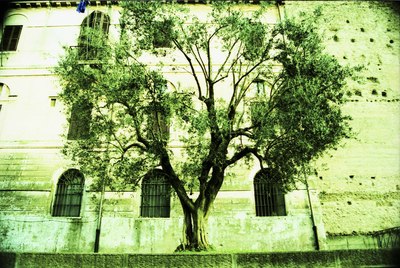

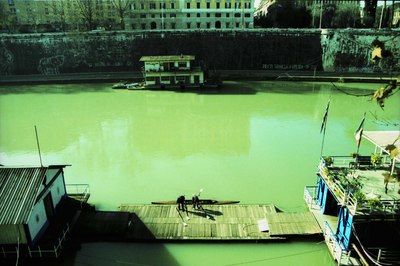

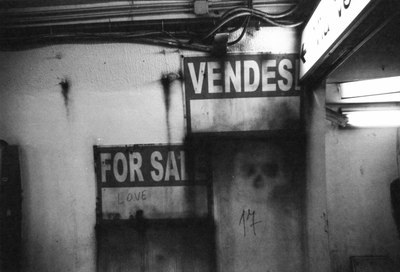

My quest is not for what places look like, but what they feel like. For me, that's when it becomes artmaking again. It's true to you, personal and specific. It's the difference between replicating and creating. What is happening now, in the air or sound of the street, that makes this January morning so unique? The literal reality of the space has been documented by others, but the emotional reality, as you feel it, has not. That is new. The light that caresses the facade just so, on this Tuesday afternoon, is fresh. It is life. The precedents for this approach have more to do with painting than photography; Turner comes to mind, and Monet, among others.

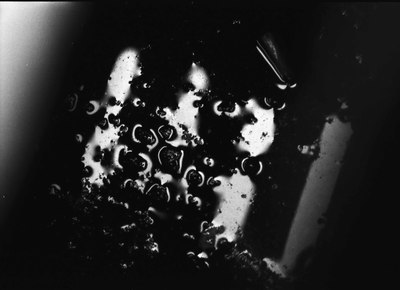

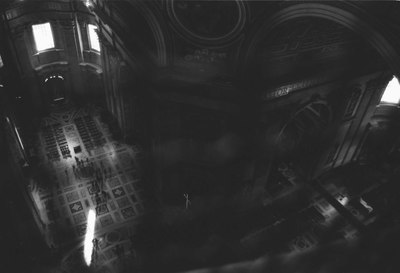

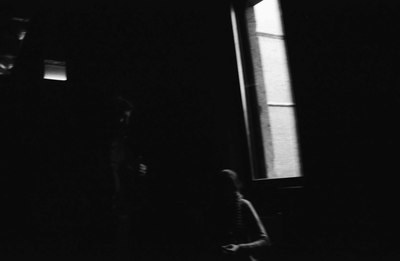

Which is how we end up with all these images of mine where you can barely tell what's going on. There's nice photos on Google of what the Vatican's awe-inspiring Raphael Room looks like. My humble hope is that my contribution is a depiction of what it felt like to stand in there, watching those dust motes drifting in the shaft of light coming through the windows. Yes, it has the effect of basically reducing the Raphael Room to a picture of floating dust, but that's where I have to ask you to bear with me!

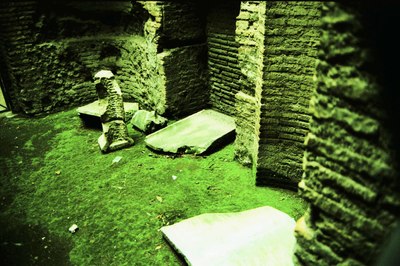

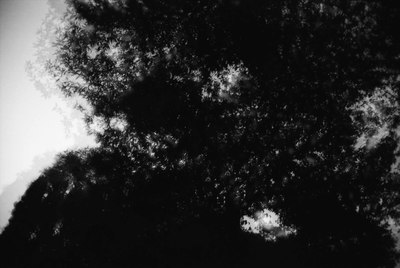

Via Giulia is now a photo of light shining through discarded pop bottles. The world-famous Campo di Fiori is presented here as incomprehensible blobs of light and plastic… the Via Sacra, one of the oldest continuously used roads in human history, shown as sunlight hitting a vague rock slab… not anachronistically, you see, but in search of the presence of the place, even if that requires putting aside the physical reality. The way those morning rays shone like magic on that stone, as it has for centuries, mere minutes after the sun had risen.

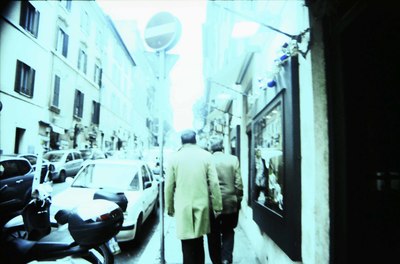

So that's why the Altare della Patria, the towering, 230-foot tall monument to a unified Italy's first king and which took nearly a half-century to build, is here shown as a haphazard mess of a street scene, because that's what it felt like to jaywalk in front of it. Or its world-famous west facade, now a blurry take of a man with a red umbrella… but I just had to do it this way, friend! The romance of the rain on cobblestone, his bright red against cool colors, the sensation of a glance– it couldn't have been in focus. Crisp details would have clouded the richness contained in that split second, echoes of a melancholy not yet arrived.

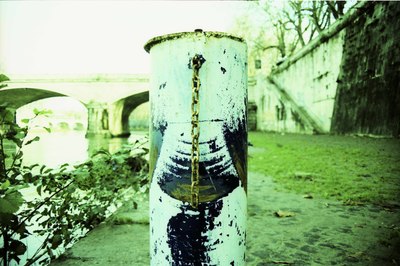

They say the best photographs are often taken around your home, or of people you know well. Why? Because you've gotten over the novelty of those spaces, and can see beyond their immediate appearance. How would a local shoot the Pantheon? Often I'll hang about a space for a while before photographing it. Although a magenta close-up of weathered pillar stone doesn't show much of what the Pantheon looks like, I hope it conveys something of what it felt like to be there. These may not look like famous or hallowed places. They are, and these are images of what I was thinking as I drifted through them, in December and January of a couple years ago.

One last thing, if I could humbly ask a favor... please, for the love of all things holy, look at these on a computer, not a phone!

Part of this was in reaction to everyone else, who rushed quickly up to the edifice, snapped a shot from their selfie stick, and hurried back to their tour bus. "People don't experience life anymore," filmmaker Michael Mann told a panel in LA last year. "They document it."

I have not lost my love for life experience, and though the selfie-sticking dashers seem to be in the biggest rush to miss out on possibly the most exciting parts of their lives, I doubt they have either. They're having a good time. But they and I are at cross purposes when it comes to artmaking. I have no interest in proving I was at the Forum or the Diocletian Baths. There isn't a single identifiable portrait of me in any of these places. I know I was there. I also have minimal interest in documenting what these amazing monuments look like. That's been done well by others elsewhere, a hundred times over. Even more pointless is taking the camera inside a museum– what will my photo of Raphael's Madonna of the Goldfinch have on the reproductions made by museum professionals with controlled lighting and unparalleled access to the painting?

What then do you do? Is it even possible to bring a fresh perspective to a city depicted as often through the ages as Rome?

My quest is not for what places look like, but what they feel like. For me, that's when it becomes artmaking again. It's true to you, personal and specific. It's the difference between replicating and creating. What is happening now, in the air or sound of the street, that makes this January morning so unique? The literal reality of the space has been documented by others, but the emotional reality, as you feel it, has not. That is new. The light that caresses the facade just so, on this Tuesday afternoon, is fresh. It is life. The precedents for this approach have more to do with painting than photography; Turner comes to mind, and Monet, among others.

Which is how we end up with all these images of mine where you can barely tell what's going on. There's nice photos on Google of what the Vatican's awe-inspiring Raphael Room looks like. My humble hope is that my contribution is a depiction of what it felt like to stand in there, watching those dust motes drifting in the shaft of light coming through the windows. Yes, it has the effect of basically reducing the Raphael Room to a picture of floating dust, but that's where I have to ask you to bear with me!

Via Giulia is now a photo of light shining through discarded pop bottles. The world-famous Campo di Fiori is presented here as incomprehensible blobs of light and plastic… the Via Sacra, one of the oldest continuously used roads in human history, shown as sunlight hitting a vague rock slab… not anachronistically, you see, but in search of the presence of the place, even if that requires putting aside the physical reality. The way those morning rays shone like magic on that stone, as it has for centuries, mere minutes after the sun had risen.

So that's why the Altare della Patria, the towering, 230-foot tall monument to a unified Italy's first king and which took nearly a half-century to build, is here shown as a haphazard mess of a street scene, because that's what it felt like to jaywalk in front of it. Or its world-famous west facade, now a blurry take of a man with a red umbrella… but I just had to do it this way, friend! The romance of the rain on cobblestone, his bright red against cool colors, the sensation of a glance– it couldn't have been in focus. Crisp details would have clouded the richness contained in that split second, echoes of a melancholy not yet arrived.

They say the best photographs are often taken around your home, or of people you know well. Why? Because you've gotten over the novelty of those spaces, and can see beyond their immediate appearance. How would a local shoot the Pantheon? Often I'll hang about a space for a while before photographing it. Although a magenta close-up of weathered pillar stone doesn't show much of what the Pantheon looks like, I hope it conveys something of what it felt like to be there. These may not look like famous or hallowed places. They are, and these are images of what I was thinking as I drifted through them, in December and January of a couple years ago.

One last thing, if I could humbly ask a favor... please, for the love of all things holy, look at these on a computer, not a phone!