|

1. Uh-Oh

Four years ago, I froze. Nothing bothers me more than men harassing women, and that's exactly what was happening on my 49 one afternoon in Summer 2020. He was big and tall, lanky, with the youthful self-absorption that breeds the worst kind of entitlement. He sat next to a young woman and leered like a Disney villain, putting his arm around her in a way that was obviously invasive. I said, “Let's try not to touch the other passengers please, that ain't polite," to which he replied, “She's my girlfriend!" The woman was silent, and I wondered if I'd misread the situation. We carried on. Ten minutes later, he was sitting behind her now, reaching around to touch her in ways that will get you arrested. She froze. I froze too. I can't blame her for freezing, but I do blame myself. I froze just as I have the times others have physically assaulted me, frozen with confusion and disbelief, confronted by human behavior I forget is even possible, and utterly unprepared to react to. After a second I said, “Okay," in a tone of deep disappointment, and pulled over, opening the doors. But I didn't know what to say next, or how. He was bigger than me. He was looking at me. He had nothing to lose. I have a lot to lose. I was frozen. She stared at me while I sat there doing nothing. I'll never forget the look on her face. Fortunately the female companion I'd been talking with up front wasn't frozen at all. She saw me look back, followed my gaze, and immediately shouted, “Hey, what the fuck, man!” My friend could do what I couldn't; a woman intervening in situations like this tends to work better than a man doing the same. It creates a sisterly two-against-one dynamic that helps tip the scales in the right direction, rather than escalating manly confrontation. Her caustic comment worked beautifully. I mumbled something in support, and the offender exited one stop later. I closed the doors after he exited, but, stupidly, opened them up again for a thoroughly oblivious earphoned-in commuter who asked to get off there too. Now I would know to refuse his request and attempt to explain, but I was still frozen. Generally, I feel like I bungled the whole affair, which was only saved by my adroit friend speaking up. I did what every good bus driver does after bungling a situation; figure out a plan for what to do next time it happens. Because whatever it was, it will happen again. 2. Once Again Four years later, I'm once again driving the 49. Another entitled man, this time older, fifty-something with shades and big headphones, coasts into the bus with a dismissive air and settles into the rear lounge. As we service the Roy Street zone he yells up toward me, “Ey driver, hold up! I wanna get some snaps o’ this!” He's eyeing a classic car across the street. I'm hardly enthusiastic to indulge such whims, but the light is turning red and I remain stopped. Like all self-absorbed souls, he imagines I acted just for him, and hollers a thank you, letting me know I can drive again. The light turns green and I do so. Operators know that in our new landscape of all-door boarding, most problem passengers enter the bus by sneaking in through the rear doors. Psychologically this is unsurprising, but try convincing administrators and policymakers that rear-door boarding exacerbates safety issues. Another man has entered, this time through the rear, and I know to pay attention. He is dressed in starchy clean, oversized, all-black denim, with spectacles and a fresh, flat-billed baseball cap. Sure enough, he begins stalking up and down the aisle, sniffing at the female passengers, sitting down next to this one, now that one, forcing them to squeeze closer to the window. He speaks in low tones; I can't make out words. Nothing backfires worse than a false accusation, so I hold off for now. What is he saying to them? Would he even respond to anything I ask? Sometimes people are too far gone to hear you. On the 7, passengers often have the street smarts to deal with such matters themselves. Less so on the 49. But here is a female college student, quiet and demure, clearly uncomfortable, standing up and moving away from the man's advances- remember how hard this is to do- standing up and moving toward the middle door, while he looks on dumbly. She makes eye contact with me. Her expression says everything. Let me out of here. Some rules were made to be broken. We're not at a stop but I open the doors. She thanks me with her eyes and is gone. Now the man in black stares at me dumbly. He says, “Why'd you let her escape?" Once again, I freeze. His sentence confounds me. Escape? My starting frame of reference for what constitutes acceptable behavior is so galactically far from his that I don't know where to begin. One stop later, two other passengers from the back walk up to me, a man and a woman. They couldn't be an odder couple- another demure college student, short and bookish in appearance… and the middle-aged man from earlier with headphones and shades, the classic car aficionado whom I'd written off as entitled. We are always more than one thing. What they had in common now was their urgency, a shared sense of mission. Both began speaking at once. “Hi um there’s a guy who's being horrible-" “Listen that dude with the hat, all in black-" “He’s harassing the women, saying stuff-" “He actin’ way outta line, jus' like she say, botherin’ everybody. You got to say someth-” "Please say something!" “-tell that fool to stop.” “I'm on it,” I said. "Thank you for telling me." 3. Go Time They hurried off (still discussing it together on the sidewalk, in a flash of beautiful bonding), but they’d done enough to burst me out of my frozen state. I love when passengers tell me. Only then am I sure my suspicions are correct, and only then am I sure others are on my side. Our side. I got on the mic. “Okay everyone, special announcement. SEXUAL harassment–” instantly I have everyone's attention- "is not cool. That's not okay. We can't be botherin’ people like that, it ain’t right. Gotta give the female passengers a lil’ bit a personal space, let ‘em do their thing. I'm really only talking to one guy, all the rest a you guys are cool. But let's try to look out for each other, try to show some respect for everyone. Thank you all for lookin’ out.” The effect I was hoping for happened: others intervened. I wanted to suggest community, standing up for the right thing, often dangerous when alone but easier in a group. I wanted the other men to know they had my respect- and, crucially, my implicit encouragement. In speaking up I was the first vocal bystander, but the critical ingredient which gets everyone involved is not the first bystander but the second bystander who takes action. The two men, and then a woman, who began standing up, moving hesitantly but firmly toward the offender, were the real heroes. A verbal tussle ensued, becoming physical; one departed, then the offender himself. We all sighed collectively, me most of all. I'd been practicing four years for that. We fail so we can learn. Regret is good, because it's proof we've grown. Own the sensation, my friend, and cherish it as you cherish yourself. When people say experience is the best teacher, they're being euphemistic. They mean failure. Regret is the purest confirmation of personal progress. Failure comes for all of us, a silent proposition, the universe waiting to see if we'll bite at the chance to improve ourselves, the chance to exercise grace, mercy, empathy. We go through our trials so we know just what to say, do (or not do) next time. So we can ace it. Don't beat yourself up for bungling things. Aspire instead, as much as possible, for that awesome, nigh-superhuman feat: To make each of your life's biggest mistakes only once.

0 Comments

This is a 2016 article I've revised and was intending to repost before news of Wiley's recent abuse allegations reached my ears. It predates that news and is not a reaction to it, but rather to Wiley's other abuses: of art, labor, and authorship, as newly showcased in recent large-scale exhibits.

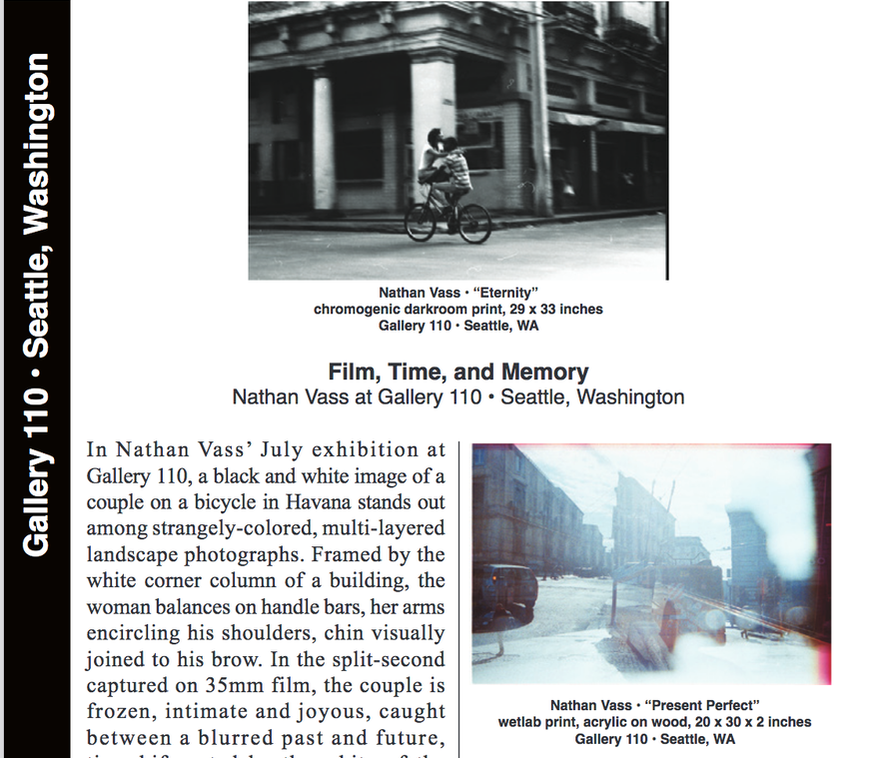

--- Some weeks ago I posted a glowing review of SAM's recent Kehinde Wiley show, which I loved. I stand by that review, but wish to add some context which I find troubling enough to consider necessary. I knew when I saw the show that Wiley didn't paint everything in the paintings, but the implications of both Wiley's and SAM's blasé attitude toward this enormous fact didn't hit me until after taking in the show a second time. The most disappointing element is the lack of demand by writers, thinkers and viewers to know who made the paintings and how. When concept takes center stage in the appreciation of art, talent, skill, and craftsmanship get relegated to secondary levels of importance, which means the authors of that skill and how they accomplish their work becomes less consequential. To look through every one of the books on Wiley at the show and have none of them even address the multiplicity of authorship question is not simply an insult to viewers (does SAM really expect us to think a thirty-six year-old is this skilled and prolific in painting, glass, bronze, and marble?), but an embarrassment on the part of the authors and curators themselves. It guides the discussion into that tiring realm where concept is king, and craftsmanship is discussed only with superlatives because critics who have no experience in the art form can't talk about it in depth, and thus focus only on what they, and anyone else with extensive knowledge in realms besides painting and sculpture, can: content. This divide becomes immediately apparent when listening to the difference between how tour guides talk when discussing art before vs. after the Modern period. Take a look at Fred Wiseman's mammoth fly-on-the-wall documentary National Gallery and listen to how the tour guides discuss Vermeer and Hans Holbein II. They talk about 1) craft and 2) how it expresses ideas. Tour guides of the Wiley show are saddled with the awkward task of discussing only the second part. I recall a particularly embarrassing moment at SAM wherein a viewer who happened to be a skilled stained-glass artist asked how a human hand could possibly accomplish the texture and shading of denim jeans on a single pane of glass, to which the poor tour guide had to reply that she had neither any idea how that was accomplished, nor who, or what, had accomplished it. We can be blunt and overstate the point by quoting Tom Stoppard: "imagination without skill gives us modern art." But I argue the real villains in this case are not the artists but those who shape the discussion. Tom Wolfe's The Painted Word is instructive here. To forget that content and form are inextricably linked is to miss much of what is beautiful about art and the decisions artists make. We've heard the phrase "style over substance" leveled against films as a criticism; as I've written elsewhere, you generally hear that phrase from people who aren't filmmakers. The style in a worthwhile art piece is the substance. Style, or form, is the language through which the content is relayed to a viewer. Form lives and dies on the strength of the artist's talent. Wiley's works would remain striking, in my opinion, after learning that he only paints touch-ups on the faces and some of the skin tones, that the figures and floral pattern work are painted by Chinese laborers, that the sculpture work is done by assistants, that the models are only paid a measly $20, and that the stained glass works are created entirely by individuals skilled in that realm (using photographs by Wiley as a base). The only thing that would suffer is Wiley's massive ego. We might also more easily understand the strange lack of passion one always detects upon inspecting a Wiley up close; an intricate but flat, uninspired collection of brushstrokes. No wonder. That the above authorship information is difficult to come by is disappointing on the part of Wiley and SAM, but so too is the lack of outcry on the part of viewers. It thusly becomes understandable that Wiley declines journalist's visits to his studio, unless it's to have Martin Schoeller take a picture of him dabbing at a canvas while sitting atop a horse; that he tells reporters he doesn't want us to know to what degree his actual involvement is in the painting process, evading questions with coy comments about preserving his "secret sauce." This is where he differs from Brueghel and Botticelli. No artist of great skill hides his talent behind a cloak of coy false modesty. If you didn't paint it, but your students did, it gets signed "School of Michelangelo." There's an understanding that it was a group effort. Practices like these have remained better documented throughout history in part because the students et al nearly always, unlike the case with Wiley, hail from the same language and culture as the primary artist. I know what you're thinking. You're thinking, Chihuly. Koons. Crewdson. I say close, but no Kehinde. They're not quite corollaries; these artists and others like them, who heavily involve assistants, don't shroud their processes in secrecy, but hold it open for all to see and determine the worth of the works. For heaven's sake, we all know Koons doesn't make his own stuff. There's another, more troubling reason why Wiley stands alone here. Unlike the folks above, Wiley's work is explicitly intended to counter the subjugation of marginalized (black) people in Western Art. Personally I love the idea. So far, so great. How does he accomplish this? By subjugating and rendering nameless the marginalized (Asian) peoples who create these artworks for him. He's eliminating subjugation one heroic step at a time, using: subjugation. Let's flip the races around and see how it sounds. The twenty-first century's wealthiest white artist creates enormous volumes of high-impact portraits of Asians, rescuing them from repression and facelessness, by farming out the work to nameless black laborers in developing countries worldwide. In gut-busting levels of hubris, said artist refuses to credit or acknowledge the specific contributions of these black men and women in the name of preserving the mystique of his "secret sauce." We're in the middle of what should be the biggest conversation in art right now. Most items we consume are created by hardworking poor people across the world who get zilch recognition. As China continues to develop and labor costs gradually rise, many manufacturing entities are opening plants elsewhere in the continued search for cheap labor. I don't appreciate this exploitative trajectory, but I can understand it. Wiley follows the trend, citing cost savings. However, he's in a financial position where this behavior is unnecessary. Kehinde Wiley is quite possibly the richest American artist of his generation. He doesn't need to be using social constructs of oppression in order to righteously attack social constructs of oppression. As one of many thousands of struggling artists of Asian descent, you can guess my perspective here. No, the fact that Wiley is barely involved with the hands-on element of his final works is not the scandal. The scandal isn't even that the authorship is kept an unanswered question. It's that the laborers, painters, stained-glass workers and sculptors are kept nameless and repressed, and no one notices, or even thinks to ask about it. That's the scandal. --- Further reading: Outsource to China, a detailed NY Magazine piece on Wiley, who candidly admits he often abandons his celebrated "street-casting" process. Kehinde Wiley's Dilemma: How the Artist Painted Himself Into a Corner With His New Works. Ben Davis explores Wiley's portraits of women at Sean Kelly. Background Considerations: Christian Frock considers the issues during Wiley's 2013 launch at the Contemporary Jewish Museum. Nay Sayin': John James Anderson explores the degree to which Wiley "keeps it real." Stop Lionizing Kehinde Wiley's Paintings. Stop Dismissing Them, Too, by our own Jen Graves. Art Access, the longstanding monthly catalogue, is comprised mostly of lists and announcements, informing readers of the month's Pacific Northwest art events. In addition to these listings, there are always (about) three feature articles which open the issue. You can pay to be listed in the directory of announcements. You can pay to have your artwork in the listings, or shown on the cover. But you can't pay to be the subject of one of those three feature articles. They decide that. How do they decide? No one knows. It's their secret sauce. I didn't invest any thought into even hoping they might choose me for their July 2023 issue, back when my solo show (more here and here) was happening. What made them decide to? How did they even know about me? Who knew Elizabeth Bryant and I would get along so well, spending an afternoon looking over work and discussing everything under the sun, going well over our allotted time in excited bonding.

Like most of the special things that happen to us, I can't explain what led to this all transpiring. To some eyes it's just another article in another publication, quickly forgotten and replaced by other matters. But for me it is a thing I cherish, not because of the publicity boost it no doubt brought (my show had record attendance), but because of the serendipity involved, the people involved, the celebration of art and a fleeting but meaningful moment of connection. More than any other piece that's been written about my work, Elizabeth gets what my work is about, and what it aims to achieve. This is the best articulation so far of what I'm hoping to do with my practice. It's short and sweet, like everything about Art Access, but what Ms. Bryant conveys in a short space is admirable for being so accurate, and so succinct. Read it here! I share love and respect because it feels good to do so. Nowadays we Seattleites are not expecting such things. People walk past me, past everyone, with eyes averted, earbuds plugged in. They assume they are hated and judged, and thusly I become invisible. They notice only what they expect. Just the other night I'd started saying, “hello–” when the guy boarding screamed so loudly everyone instantly looked up: “SHUT THE FUCK UP!”

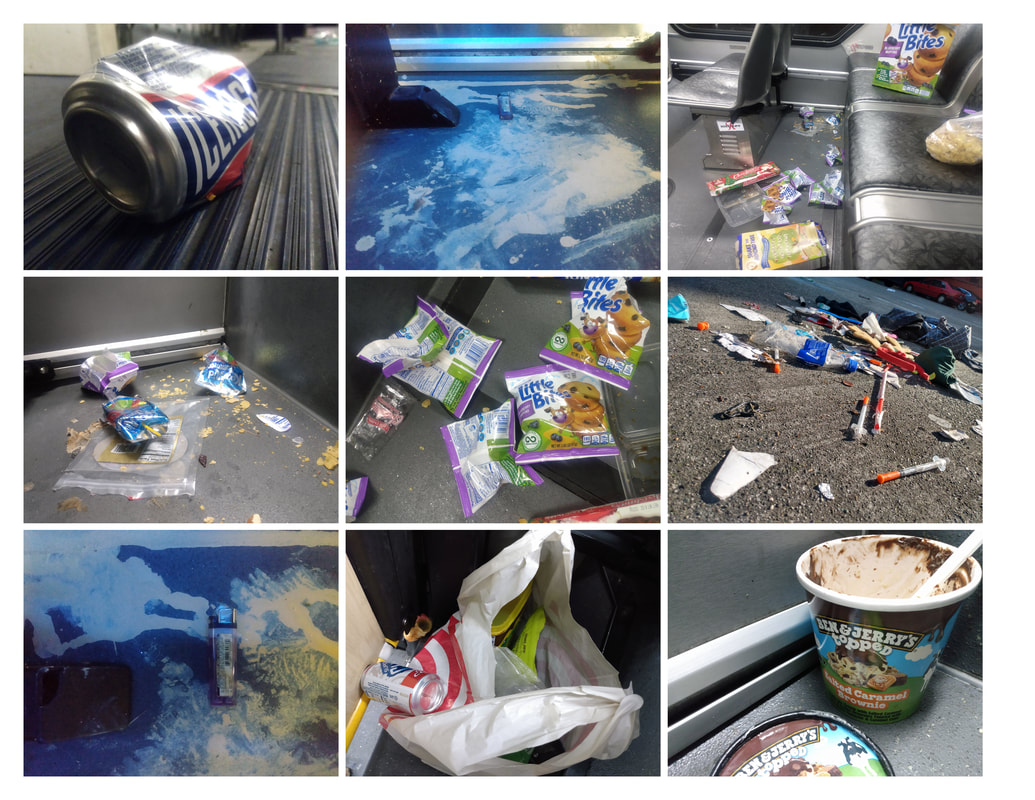

Tonight I explained to a passenger, "They think I'm mad at them, and I haven't even done anything!" She burst out laughing. "Honey, if they think you're mad… it's them tha's got somethin’ wrong with them! I been riding your bus for how long now? It should be obvious to any, to any sane human, that you're respectful, tha' you tryna be nice!" And yet, if you're as convinced of the world being against you as some of these folks are, you won't see anything else, obvious or otherwise. I feel like an anomaly these days. Life in the developed world post-2020 is all about escape– from reality, obligation, introspection and most of all, other people. In this manner some find an overlap between fentanyl and smartphone addiction, as both seek to reduce sensory experience, to remove us from reality. I enjoy phones as a tool but I aim in the opposite direction, seeking refuge in the present, in direct contact with others. I still say hello because maybe, just maybe, it’ll reach them. Shutting the world out is easier, yes, but we forget after a while how good it feels to connect with others. The sensation of belonging. I want to offer that, keep it alive. Here is a woman with more than twenty Safeway grocery bags laid out on the bus stop sidewalk. I step off the bus and help carry the bags aboard not because I like her (I don’t), not because it was smart to buy that many groceries and have no way to carry them (it wasn’t), but because she's human. And because it's what the best version of myself would do. You know this feeling. As I duck in and out the front doors with bags in hand, an elderly Somalian woman tells me, “You’re a good driver.” She had never spoken to me before. Yes, part of me melted inside. Later, while the grocery-laden woman was cursing someone out and as I helped her with her last bags stepping out, I found myself chatting with a regular on the sidewalk. He leaned on his cane. "You know, the last two buses passed her up." I looked at the massive quantity of ice cream she'd spilled on the bus floor. Fentanyl annihilates blood sugar levels, which is why you see people huffing down stolen Tillamook and Ben & Jerry's on street corners everywhere now. "Well, I don’t blame ‘em," I said. We do need operators who'll pass this sort of thing up, or else no fare-paying passenger would ever get anywhere. But my issue is that I'm Nathan. "My problem is, I’m too nice, man! I can’t help myself!" "Hey, nothin’ wrong with that!" A couple of strangers standing around in the comfortable twilight. I talk to older folks more regularly now. They get it. There will always be those of us who like to gab it up. I leaned against the zone flag and said, "My question is, how the heck is she gonna get all this stuff home?" He chuckled. "I know, right?" "You gotta think about stuff like that when you’re at the store!" We vary in our capacity for abstract thought. Some of us think ahead, and some of us don't. In more than one way, she didn't, but at the end of the day those details fall away like so much chaff. Years from now I will not remember her particulars. There will simply be the memory that I helped someone that day, stretching my legs and talking to the person next to me, trying to be my best self. The memory will contain the fact that it felt good to do so. Short one this time– I post new material on the 1st of every month. Check back went rent is due!

I've been working later than usual, at an inconvenience to myself (no transit runs to my home in those wee hours), because it's so deeply satisfying. Something happens after 23h00, cruising down Rainier, nodding and waving goodnight to my regulars. Why do the stakes feel lower, the world smaller and more your own, with more space and time to be? In the midst of the evening 7's fifteen-minute frequency, there's a 30-minute gap in the southbound service at about 22h30. It's a scheduling error, and it's been there for years. I've given up complaining about it. There couldn't be a worse time for a gap in nighttime service: the 22h00 hour contains a "rush hour echo" as the swing shift workers make their way home. My 23h00 trip is filled with a double load not of sleepers, but commuters. I knew about that issue for a long time before realizing this past year that I'd picked a piece nearly every night containing that very trip. The busiest consistent nighttime trip on the 7. I sighed when I discovered this, but now I feel a strange relish doing it. You feel important, carrying two trips worth of people who actually need to be somewhere. These guys want to go home. For some reason Metro assigns a small bus on the run every night, so it's packed; but we make it work. While the institutions fail us, we can tend to each other. I greet them with a smile, with respect and love. By now they know me. No one complains. We're doing what we can, happy to be here. It is hard, yes, but good. Why choose easy? When did easier become better? Are not the harder thing, and the right thing, usually the same? What is living, if not embracing struggle? I was lucky enough to meet Dr. Wirth through a mutual friend. Some people strike you deeply, if such a thing is possible, not with their prestige or accolades but with their unassuming nature. You know beforehand of their significant accomplishments, but upon finally meeting are most impressed by the their warmth and humanity. Where their CV isn't the crowning definition of their identity so much as, quite simply, their kindness. Their humanness. People like to hide behind accomplishments. I'm more impressed when someone prioritizes not their resume but goodness, putting people first. It's so easy to get caught up in what we do; but what about who we are? This blurb of his accomplishments– "Dr. Wirth, PhD, is an American philosopher and professor of philosophy at Seattle University. He was the Theiline Pigott McCone Chair in Humanities from 2014 to 2016, and his books include Commiserating with Devastated Things: Milan Kundera and the Entitlements of Thinking, Schelling’s Practice of the Wild, and, most recently, Nietzsche and Other Buddhas: Philosophy After Comparative Philosophy." –like many blurbs (including my own), reveals very little about the person in question. Yes, those are indeed excellent works he's written. But my desire to share his words on my film stem from a deeper appreciation for his personhood. Where the books are merely an extension of his being. I aspire toward something like that. The film is an amalgamation of things I've reflected upon while in the presence of giants. Here are further musings on those reflections, by one I'm lucky to have met. --- Reflections on Men I Trust I have long thought that in the face of death, especially the death of another, we all become, at least for a few minutes, philosophers. Given that philosophy opens the possibility that we might speak to death and face it directly, we typically turn away, revealing our philosophy to be merely the kinds of self-deceptions that had already governed our living. This deeply moving film, free of all sentimentality and, for that reason, all the more moving, derives its power by standing in the white heat of this moment as death exposes human living as without “why” and cancels for the dying all of the scientific “hows.” Just as life does not need to be filled with the extraordinary and the spectacular to be precious and intrinsically good, so this film concentrates on the supposedly ordinary, which, cast against the background of its loss, reappears as sufficient in themselves and boundlessly precious. Without retreating into the abstract, this is also a film about time—yes, death proves time. As such, however, it is allows the power of the moment to appear: not how something is, or why it is (as if explaining death either justifies it or renders it more palatable), but rather the infinite preciousness—and fragility and impermanence—that it is. Mahayana Buddhists call this suchness, things just as they are—fleeting, impermanent, and yes, enough. It is enough that they are simply what they are. They did not have to be more to be worthy of cherishment. Technically, the editing is also a marvel as it layers and juxtaposes moments of time, each moment suddenly appearing precious: drinking water at the bar, dancing with your sister, speaking French, discussing whether to have children (and the problem of legacy as if we can cheat death by leaving something behind). Even walking in the forest to scatter ashes. Despite our ecological rapacity, there are still sword ferns and western red cedars and western hemlocks and Douglas firs, and their power remains in this moment irrefutable: that they are there. I loved this film. It is beautiful and honest and it moved me to my core. --- Read other reviews of my film here. Learn more about the film at its official page, or check out the trailer below. Contact me via the About page if you'd like a secure link to see the film! I. Repulsion

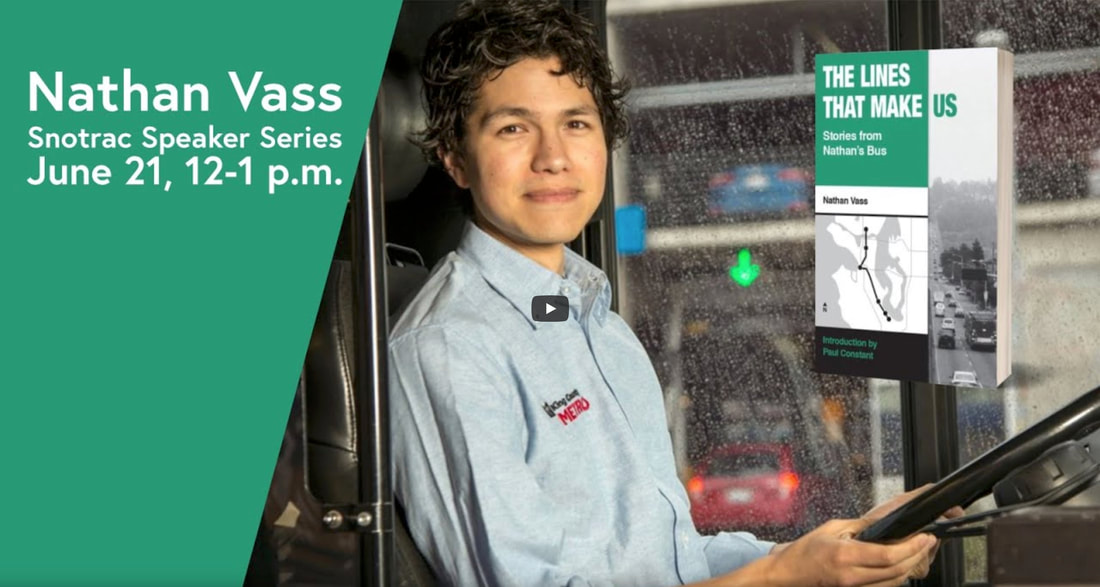

They slobber past you with their bodies, at once aimless and committed, a sort of slow-motion resolve in that stumbling post-COVID gait we now know so well. Never before have they existed in such casual profusion. There were more closed doors back then, places to hide, institutions to rely on. Now things are different. As long as drugs are more accessible than solutions, people will medicate their problems with the former. You can kill yourself at Third and Pike now for eighty-eight cents. It is easy for we the sober-minded to laugh, to marvel at the stupidity of strangers. Look at them, sagging their pants below the knees, fishing through litter, pawing at the cement not for scraps of food but for the smallest, most unlikely hint of a fix. Here is one sitting in a pool of his own excrement, another huffing down stolen ice cream to rebalance his blood sugar, snot glazing across his mustache and lips, feeding into blood from open sores. “They pay money to look like that,” a scruffy but drug-free passenger on my bus chuckled as he watched them outside, incredulously. “They actually pay money to fall asleep! Idiots. Dumbasses!” Look at their muscles collapsing from the hips up, a new generation that stands with head and knees at equal height, legs bent and bending lower, keeling over from a high finally, reaching for the earth’s opposite horizon. The comical walk and Dickensian squalor of their clothes and skin, almost a dress code by this point; we call them lost, these haphazard solipsists, slinking ever onward in their knock-kneed gait. They are so easy to ridicule. II. However There is always a however, and never moreso than here. We the Sober can involve the future in our decision-making. We can consider others. The addicted brain does not. Its comprehension of the future only extends as far as acquiring its next fix: an hour maybe, or less than that. Life is measured in blinkered minutes. Only in such a tunnel can the decisions we see out here begin to make sense. Do you know what an accomplishment it is, to resist a pill? To flush your supply down the toilet, say no, ask for help? These are actions harder and more worthy of our praise than winning the Nobel Prize. The trepidatious tender courage needed moves me more than those who win elections, run companies, more than lofty resumes and mantles stuffed with trophies. Is an achievement somehow less, because it goes unrecorded? Particularly with what I know about addiction’s effect on brain chemistry, I bow to the person who finds it in themselves to refuse a drink, pill, straw, needle, powder, patch. These are the silent accomplishments. Imagine regarding your strung-out self in a bathroom mirror (at a gas station, at a mansion), and seeing those gaunt eyes staring back, as you remember who you thought you could one day be. Not this. You remember you can still start over, and then you do so. You act. That is the battle these people are trying to win. It is a shameful and humiliating battle but they fight it in public, ignominiously, while the rest of us shake our heads and judge. These people deserve pity, not ridicule. “They” were all you and me once, children with prospects and dreams, things that made them excited and sad and hopeful. They did not know they would one day start fights over nothing, soil themselves in public, walk into the road not caring if they live or die. They did not know the halfway point of their lives when it whizzed right past them. III. Personally I attended elementary and junior high school with a girl named Alana. Being the same age we shared many classes, sitting next to each other in Math and Language Arts, and again in Social Studies. She was pretty and kind and smart enough. Many years later she'd board my 3/4 with her Shih Tzu in tow, surprised when I remembered her full name. She recalled mine as well. We trundled down Third Avenue in good spirits. She was searching her cluttered bags for her phone, thrilled when it began ringing. “Bye, Nathan Vass!” she called out as she left. Everything seemed fine. Then I would see her intermittently, across several years. A decline was underway. I began seeing her in the unforgiving back alleys of the city, too much makeup now, a puffy jacket and flip-flops in cold weather; with different men each time. Shame crept into her gaze, and then the rest. The only constant was her smile to me and the dog, always her faithful Shih Tzu accompanying her. “I'm glad he's always at your side,” I'd say. “We've been through a lot together,” she'd reply. Alana would die before either of us reached twenty-five. Alana McCrawley from Math class and Language Arts, who remembered my full name. Her dog would end up outliving her. What was her final thought? I stop for the people at 12th and Jackson. I don't pass them up, and they know that. I want them to know that. Somebody there will always wave if they want me, almost frantically, because they’re so used to being passed by. I respond with my own wave. Some of my favorite passengers out here. “Aw, it's Nathan,” one said recently, with happy relief. “He's not gonna fuck with us!” I want them to know my bus is a little different. This is the guy who cares, who doesn't look down on us. That's what I'm trying for. Some of them will make it out and live to tell me about it. Some already have. Others of us don't know that we'll unravel, a paycheck or a bottle of pain medication away from Western society's most slippery slope. Maybe it'll be us one day, stumbling against glass and concrete dirt, another slipshod pants-sagging drifter in search of joy, meaning, conscience, belonging… wondering where it all went, baffled by how elusive those things are now. Who among them used to have it easy? Who among them once snickered, looking outside, really believing themselves as they laughed, that'll never be me. Do not be too quick to sneer. The story is not over yet. --- More on this whole situation here: State of the (Seattle) Union We are still in the era of virtual events. Here's another, now passed but recorded for your pleasure– wherein I discuss all things transit, COVID, writing, kindness, and the condition of the street. Like all Zoom videos it's not up to snuff in terms of the cinematography and image quality that we might prefer, but hopefully the content is enough to maintain interest. Huge, huge gratitude to Brock Howell and everyone at SnoTrac for putting this together and hosting me. It was an honor and a treat to meet you all! For more speeches and talks of mine click here. Enjoy! I get as many, if not more comments about my book now than I did when it was a bestseller four years ago, back during those long-lost pre-COVID days. We see differently now, and know to value certain things which we previously took for granted. With the advent of certain social justice movements there are obvious ways in which the book has become more topical, but there are also other things the book celebrates, which feel rarer now and thusly more precious, more worth cherishing. It isn't just institutional competence which has faded from view. There are actions we can take as individuals, ways of choosing to see, which feel deeply valuable in this new time. It is lonelier to realize them, and sometimes feels more hopeless, but it is worth it. It is worth it for the occasional burst of joyful light. It is worth it because like attracts like. We find each other by being our best selves.

And it is worth it because you don't change the world by trying to change the world. You do it by changing the person next to you. And how do you do that? Not by trying to change them (you can't), but by being your best self. Leading by example. Motivating the people around you to observe, reflect on, consider how you choose to live life. You can be the light. I know that's harder to do now, but it's in exactly these sorts of times when it's most needed, valuable, and inspiring. Thank you to the people around me who glow, who inspire me every day and night, from my closest friends to my colleagues down to the faces on the street which beam out gratitude and present verve. Please enjoy the video above, which is two stories from my book, along with an introduction situating how the book plays in today's landscape. Many thanks to the fine folks at Chin Music and AWP at large for hosting me. I post new material here at the beginning of every month. Check back every 1st! “Researchers detected methamphetamine in 98% of surface samples and 100% of air samples, while fentanyl was detected in 46% of surface and 25% of air samples. One air sample exceeded federal recommendations for airborne fentanyl exposure at work established by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.”

These facts, and a host of others included in UW’s excellent new study, will surprise only those who don’t use transit. For the rest of us they confirm, finally, in concrete terms for all to see, a sense of what it is to work with the public on street level in post-COVID Seattle. I encourage reviewing the report itself, not just the press release or even the executive summary. There's a lot in there, and it can't be summed up in a word, other than to say that Marissa Baker, PhD, and team’s study is the first of its kind. No entity has studied the presence of airborne drug fumes in public spaces before, and Seattle is the ideal metropolis to start with: a city where non-users are forced to inhale fumes of the deadliest street drugs in existence, day after day. Some of the findings are comforting; some of them aren't. We will continue to hear compelling pieces of political rhetoric, well-crafted speeches and declarations. We even have a brand new law allowing prosecution of public drug use (though no plan for how an overburdened judicial system would accommodate those arrests). It can all sound so promising on paper. But then you walk outside. What defines an activity as legal, or illegal? While a piece of legislation may declare a given activity unlawful, what matters is what the real-world consequences are. Needles, fumes, torches, foil, straw, brain damage, overdose– it is all 'legal,' practically speaking, because it is tolerated in broad daylight without consequences. My first experience with fentanyl was returning to the E Line after ten years away from driving Aurora Avenue. A young mother came forward to apologize for her toddler son, who'd vomited on the bus floor due to fumes coming from the teens smoking right next to them. Neither she nor I knew what fentanyl was back then. The mom escorted her sick child off the bus in bewildered confusion. An off-duty security guard riding homeward had to explain to me what just happened. This was the new status quo. Third Avenue is populated primarily by commuters; the unhoused; street people; first responders; police; cleaning crews; and bus operators. These are the individuals most qualified to have an opinion on the state of the street. They extend over all political backgrounds, but there’s one thing they all agree on: Downtown Seattle is in terrible shape, and has seen no meaningful improvement in over three years.* If anyone’s telling you Third is now safe enough to take your kids or your grandmother, they’re not spending enough time outside. I’m waiting for change I can discern outside of a newspaper. Studies like UW's are at their most valuable when they reveal ongoing institutional incompetence. There is more research to be conducted, and we should keep asking questions. But we know enough to know things need to change. What action besides words will we see? After the dutifully fervent press releases and concerned memos have aired, what then? Will my colleagues still have to call off sick on the road because of the resultant lightheadedness fentanyl causes? Will they, many of them new parents, see their long-term health impacted? Some have failed drug tests as a result of the work environment (which, now that we have the above data, should no longer be shocking). Will they have to face consequences they don't deserve? And all the while, my friends on the street. Will they still tell me of their companions overdosing? Will I continue to have conversations with parents where there is more silence than words, where what is communicated is too devastating to speak out loud? We were the city of the future. What no one in our past could have anticipated was a world wherein a public crisis is met by leaders not with outrage, not sophistication, not solutions… but indifference. Hand-wringing, squabbling, and lip service– that is, the appearance of action– has taken the place of action. When the only entities with the power to exert widespread change are structured like corporate bureaucracies, you know you’re in trouble because no organizational structure is better suited for abdicating responsibility.** Top-heavy managerial hierarchies seem designed for such abdication. It’s always the fault of some other department. They’re looking into it. We’re so sorry. Let me redirect your call. Pardon my scathing tone. I do not wish to offend, but to awaken, like a parent who knows she must use a firm voice, who does so because she wishes to impress upon her child the gravity of what’s at stake. By now it should be obvious that the powers that be (I’m not pointing fingers at Metro but at a far larger and more directly responsible municipal government power structure) do not care about their constituents. In this approach they benefit themselves in the short term… but not in the long term. Street people vote. People who are afraid to go out also vote. People concerned for the welfare of their fellow citizens, for the health and safety of themselves and their children… all vote. If a politician’s primary goal is to get reelected, they would do well to remember this. You need people to believe that you care. One way to start is by effecting discernible change. Metro made its name on addressing a public health issue. James R. Ellis and others tackled a problem in 1960– wastewater treatment– and handled it so well the newly-formed group was given 100 days to put together a transit system. They succeeded mightily, starting a tradition of “failing forward” with innovative, concrete action and demonstrable results. Metro is now faced with another public health crisis. I believe if it had the autonomy to solve the situation itself, as it once did, it would by now have done so. But it no longer has that freedom. Metro is more or less run by the King County Council, who is itself beholden to abide by state laws governing what can and can’t be done, and for how much money. As ever, the ultimate decisions will be made by people who don’t ride buses. By politicians who never set foot on Third Avenue. They don’t know the state of things out here. They don’t know our faces, lives, troubles. They haven’t lived the risk, felt the exposure, the wounds of mental and physical pain. If they did, things would've been fixed long ago. Most humans empathize with only the people they see in real life.*** And these powerful, well-meaning, and probably genuinely concerned folks aren’t coming out to see us in real life. If only they had the requisite courage and brass nerve to come down here and see. How will Downtown Seattle look and feel one, five, ten years from now? Time will tell. Since my long term health– that is, my life– quite literally hangs in the balance, I'm as curious as the rest of us. Meanwhile. What are we individuals to do, besides vote? What am I doing, out here in the maelstrom? What I can. My arms reach a few feet on either side of me. That is where I can effect change. I greet the passengers at 12th and Jackson as the fellow humans they are. (Remember, fentanyl users aren’t dangerous. They’re generally catatonic. People with schizophrenic disorders, on the other hand….) I treat the people around me as if they’re already my friends, and it works wonders like you wouldn’t believe. I do it because it makes me feel good. Interacting with strangers has been scientifically shown to improve one’s well-being, sense of belonging, and overall happiness. I give, and give, and give respect, love, acknowledgment, and on a long enough timeline it comes back around in spades. It rejuvenates me. This beautiful cycle does not require a functioning government, nor a city with its municipal affairs in order. Thank goodness!!! --- *Further reflections (and nuance) in my deep dive on all things drugs and Seattle, here. **Anna Patrick at The Seattle Times reveals which promises made on homelessness were broken, and how, in these two excellent breakdowns from 2022 and 2023. ***If you’ve been wondering why empathy’s been on the decline, this may be a factor. People spend less time with others in real life (or IRL, as the kids say) than they ever have. This is also why depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation are higher among young people than they’ve ever been. More here and here. Lecture by me on this subject, with works cited and further reflections, here. |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed