|

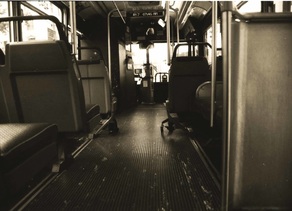

Is it so silly, when we really think about it, to mourn the passing of a coach type? Think back to your childhood haunts. The wind chimes on Grandma's porch. The smells of your home, wherever it was, during the best years of your life. They form the texture of our existence, these spaces. The building blocks, how we make it personal. Even if you never rode them, it's likely Metro's sixty-foot Breda bus made an impression. They were ancient. They were massive. They looked so big and so heavy you'd think they should be illegal, and they were. At 64,350 pounds with a full load of passengers, they destroyed roads and violated weight limits all across the county, forcing Metro to pay fines every single service day for a couple decades. They were unstoppable tanks that could barely get started; they employed a different sort of transmission than what we ordinarily know, which is why you'd get all the way up to fifth gear and the bus would still only be going twenty-five. You needed to pack a lunch for some of those steep hills. The manufacturer's top speed was set at fifty-five, which in real life meant something like fifty-one or fifty-two. Forget schedule. "They were stinkers from day one," a senior operator not-so-wistfully told me. They predated ergonomics and have destroyed countless drivers' shoulders, knees, lower backs…. And oh, how I love them so. They live now only in our thoughts: the last Breda coach, ever, ran its final trip last Thursday on an inbound 36, sometime around 1pm. The photos you see here were taken by me between 1998 and last month. As an operator, my body certainly won't miss them, but I will. I'll miss the fact of their colossal size. Twelve feet tall rather than ten, four steps instead of three, the high center of gravity that felt like a streetcar in prewar Europe; I'll miss the stained and paint-stripped floors, panels gouged with twenty-six years of peeling and knifepoint graffiti, lint and litter becoming one with the bus, fusing together in the dusty nether corners. A biologist's dream, I'm sure. Think of the histories they've borne witness to, the wars and presidents their passengers have discussed. People sat in these things reading about Tiananmen Square and the overthrow in Romania. They asked each other what the internet was. Made in 1989 by the Italian company Breda, which specialized in trains, the Bredas were the first dual-mode buses in North America. The only other Breads in the world are in Milan, pictured below (from 2015, as they were being phased out): Only the Seattle coaches had a rear axle connected to a diesel drive train and a center axle another power source: an electric motor, which came to life when the poles on top of the bus were raised up to trolley wire. They were a custom order designed for Metro's downtown transit tunnel, which opened in 1990, and featured trolley wire running its length to allow coaches to whisk through without emitting exhaust fumes. The process of raising the poles to the wire at either end of the tunnel wasn't always flawless, but wasn't that part of the charm? As a child, it was a treat to feel the bus shift into electric. You were sitting in the same vehicle, but all the sounds changed. No more rumbling, shifting, or engine vibrations; now the steady hum of current, accelerated torque, and clicks of poles switching tracks. Out-of-towners marveled, trying to figure out what was going on. The initial order was for 235 buses. From 1990 to 2005 they traversed all over the county, breaking down, giving millions (not an exaggeration) of rides, raising the poles and lowering the poles as they went in and out of the tunnel, tearing apart drivers' shoulders, and proving the bane of every automobile who ever got stuck behind one, wondering why the bus in front of them was taking more than a mile to get up to fifty (again, not an exaggeration: on the 267 from the West Lake Sammamish onramp to SR-520 & 51st, there was no way the bus was getting over twenty mph, despite the 60 mph speed limit). Part of the issue was weight. In the analogue days, dual-mode meant, quite literally, doubling everything: there weren't just two engines, but two of everything: brake systems, transmissions (as much as an electric motor could have one), all the connective assembly for each, and more. In 2005 the vehicles were replaced by new Hybrid diesels which you still see in service today. At a downright puny (well, comparatively) 44,935 pounds, these are veritable jackrabbits. They're little sports cars. They number 2600-2812, and are identifiable by their roof-mounted battery, instead of poles. Yes, they make more sense, but they're not as endearing. Though they do have an electric assist that allows them better acceleration when operating under forty mph… admit it, friend. They lack character. There's something about design from the pre-digital period I enjoy: look at the knobs and dials on cameras from back then, or the unfussy current collection boxes atop the bus. The sharp edges and corners, so un-aerodynamic. And so hot. The person who isn't trying so hard to look good ends up being the most dazzling; you know what I mean. And so it is with bus design. Listen to that "ding" of the bell chime: that's a real bell. Not everything needed to look like a slick sci-fi movie. The dashboard was drenched in toggle switches and buttons, in a triumph of function over form; today's dash is sleek but limiting by comparison. The driver could engage the differential lock, disable the dynamic brake, cutout the retarder, and more– no longer options today. Upon being replaced in 2005, 59 of the 235 Bredas were selected to continue service as electric-only trolleys, replacing the aging fleet of 46 German MAN trolleys from 1986, pictured below. I'm even more attached to those than I am to the Bredas; good thing you don't have to listen to me rapturously proclaim my love for them here.... The 59 remaining Bredas would now be used on trolley routes rather than tunnel routes, and drive only while on the wire– the diesel engines, transmission and radiator were removed, making them 14,000 pounds lighter. Great. The buses were retrofitted with new signage, seat upholstering, Kiepe fiberglass poles (more flexible than steel, better at staying on the wire), updated driver's area, and reduced seating to allow for more leg room (people don't squeeze in quite like they used to!). The haphazard, in-house nature of this refurbishment led to the moniker "FrankenBreda." Say it with love. With 59 buses, you'd think maybe 55 or so of those would always be in working order and ready to hit the road. Wouldn't that be nice. But being that these are Bredas, no amount of cute new upholstered seats could alter the fact that they were king of breakdowns, and always would be. A standard bus fleet requires a ten or fifteen percent "spare ratio–" an extra quantity of buses on the lot to mitigate breakdowns. Ten or twelve buses for a fleet of a hundred, for instance. Bredas broke down so much Metro needed a thirty percent spare ratio– to address the constant breakdowns but also to have available for scrap parts. Spare parts for a bus made by an Italian train company while the the Berlin Wall was still standing are hard to come by. When you step into the bus to start your shift and notice that the odometer reads over 600,000 miles, you're not really expecting this thing to work anyway. No need, for instance, to write up the damage to the cracked bumper below; you would be more surprised if everything actually looked good. As much as we loved complaining about them ("why do they smell so much" being a query I heard with unusual frequency), what made them so incredible was how often they did run without incident. What an ace crew those mechanics are. Metro loves getting every inch of life out of their coaches, and with trolleys it's possible. Trolley bus motors last forever because they contain almost no moving parts, relatively speaking. The new fiberglass poles worked like a charm, and if you lost your poles it was likely due to driver error, rather than mechanical failure: too fast through a switch perhaps, or a forgotten turn signal (turn signals send radio signals up to the wire to switch the tracks). They were notoriously difficult to give a smooth ride, but it was possible. No other articulated bus in the fleet is driven by the center axle, and these were thus tanks in the snow; having the added dashboard controls mentioned above helped as well. Sometimes the dash lights would be burned out, or the tires bald, or you just got tired of the drafty interior, the dented and cracked facades, turn signals you had to stand on to activate, eight hours of the scent of a chemistry experiment gone horribly awry, baking in the summer without air conditioning, sweltering in the glass box behind those enormous windows… Ah, but when was anything easy truly worthwhile? The challenge of the untamed beast made you a better driver. They made tighter turns than any other coach, had better visibility both inside and out, doors that didn't take forever to close, a back window, a heater that worked, and, as trolleys, tremendous torque– it hardly made sense that such a lumbering behemoth could get up and go so fast.

But the real jump they had on all other buses was history. There's something larger here than gearhead nostalgia. Unlike most countries, ours is eager to turn away from its past, to subsume it with glossy new facades. The West Coast cities in particular seem eager to erase the evidence of time, and it isn't just because they're newer. There was life here more than fifty years ago, but you'd be hard pressed to find it now. Where are the actualizations of the lives of our local forefathers, the Dennys, Yeslers, Sealths, aside from the pithy plaque or statue? Where are the deep shades of faded brick, the echo of trees and buildings which predate the lives of our families, when homes and shoes and toys and clothes were built to last? In a world that starts and spurts through change without pausing to take stock of itself, any sign of constancy is a deep comfort to me. That is what that whisper is, that subtle reassurance we feel when confronted with trees standing tall against the horizon, the home you grew up in which is still standing, and yes, this strange and glorious Breda monster, old and weathered enough to be a father figure in its own right, gently reminding us that the we and the world will, as ever, continue.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed