|

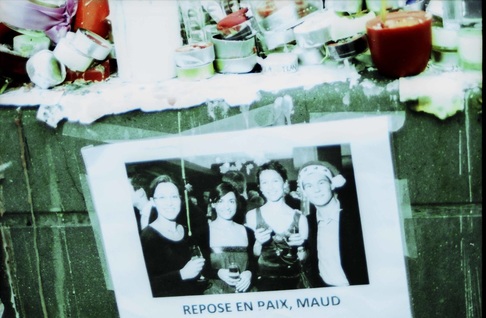

Almost exactly one year ago, I was sleeping fitfully in a small room on the upper floor of a hostel in the 19th Arrondissement in Paris. I may have been dreaming of my parents. Earlier, I'd been lying in my lower bunk studying the city map, memorizing where I'd explore tomorrow. Examining the metro map, the phrasebook. I don't travel with electronics; why let your phone do all the heavy lifting, when you know you can? I couldn't have known then that none of those plans would materialize. I didn't know that mere hundreds of feet away, ordinary folk like myself were being murdered, and that by morning there would be 550 newly dead or injured bodies, the lives of all who knew them forever altered, shaken by the size of history replacing daily life. The city would shut down for three days of mourning, by its own will and that of its leaders. Empty streets in every direction, hollow, missing human life and heavy with something else; a fraught and massive bulk invading our thoughts, the nameless weight that makes grown men stand still. For me there is before Paris, and after Paris. The event began when I was four blocks away at a laundromat. The city was loud enough that you couldn't hear gunfire. Laundry is important to me when traveling: I pack only one pair of black jeans regardless of duration of travel, plus one pair of sweatpants to wear while washing those jeans. I was enjoying the mix of domestic bliss and urban exposure laundromats offer. That's what I was thinking about, zen-ing out to the rotating whir, trying to understand the French dryer instructions. I changed and met a hostelmate for dinner, as planned. It was Yi-Syuan's last night in Paris, and we treated ourselves to a "real French dinner." Our restaurant was hardly any different from the ones down the street which got shot up– festive, busy, delicious. She was a student about my age from Taijung, also traveling alone. We sat by an open window, oblivious to history. We knew we'd never see each other again, which meant we could discuss anything, anything at all, our deepest secrets, confusions, fears, hopes. It was a dinner for the ages. I've never had another like it. Mere blocks away. Why did I live? Why did she live? Imagine the nightmare for the 137 who were dying, the last moments, the final view from dying eyes, the final view and also the worst. They met their end on a Friday, out on the town as I was, taking in food and good company in that huge, beautiful, complicated city. Until that night we all had something sacred, which we held dear in our different ways: a notion of a just universe. How do we keep that notion? Where do we go now, and how do we think? There is something I don't understand. I cannot, for the life of me, grasp why such horrible badness befalls such good people. I realize this dilemma has been debated since the dawn of civilization, implying no one else knows the answer either, but that does not comfort me. There are times when I am haunted by the unblinking silence of the world. I try to remember all are good and bad, and none are good and bad. Our nuances transcend such categorizing. In my own life, I am convinced it is the best people I know have suffered the worst agonies. It seems obvious to me, and yet it is possible everyone feels this way. I try to recognize I know the misfortunes best of those whom I love most, that everyone else has their misfortunes too. The photograph above was taped to the base of a statue, one of thousands of other objects, mostly letters, flowers, and candles, together forming an impromptu memorial in the center of a large plaza.* There were not many photos, and thus this one caught my eye. I knelt down low to look at it. One of those faces, or maybe all of them, were alive earlier that week. The mourning figures around me, the candles and slogans and statues and blood all receded into my periphery. There was only this picture. I thought of Maud. I looked at their faces, young people with goals and dreams. I thought of the men who killed them, young people too, children once. I haven't ever cried in the company of a thousand strangers, but I did then. These people are my friends, I thought. Why did you destroy them? Why did you break the lives of all who knew them? You are my friend too, in that you are human. Why did you do that? Did you not know it would break you too? Have you ever known anyone to get away with anything, ever? When we discuss the meaning of life, we are usually talking about the meaning of tragedy in life. Aside from the question of why we exist in the first place, the rest generally makes some kind of sense. But what to make of the suffering foisted on good people? This cruel riddle is both smaller than the fundamental query of why we're here, and at the same time more relevant. Because if we knew the answer, we would achieve the miracle of being at peace with all acts of man and nature. The answers and religions we offer each other are suppositions, the best of them based on experience, each carrying their different rings of truth. I recall now the definition of optimism I've written about before, a creation my parents and I once came up with: being comfortable looking at truth, even when it's negative. I recollect the Taoist principle of accepting everything in front of you without wanting it to be any other way. These maxims make life easier, but one day you will come upon a situation where abiding by them will feel like a crime. A dying loved one; bodies in the streets. It is so hard sometimes, so impossible. But we must do it. We have to try, or we will never find peace. -- *Place de la Republique. For more photographs of Paris at the time of the attacks, click here. Thoughts written immediately after the event. An open letter to terrorists around the world. -- An excerpt from a conversation circa 1883, between Indian mystic Ramkrishna Paramahansa and his chief disciple Swami Vivekananda, which might be of interest: SV: "Why do good people always suffer?" RP: "Diamond cannot be polished without friction. Gold cannot be purified without fire. Good people go through trials, but don’t suffer. With that experience their life becomes better, not bitter." SV: "You mean to say such experience is useful?" RP: "Yes. In every term, Experience is a hard teacher. She gives the test first and the lessons afterwards."

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed