|

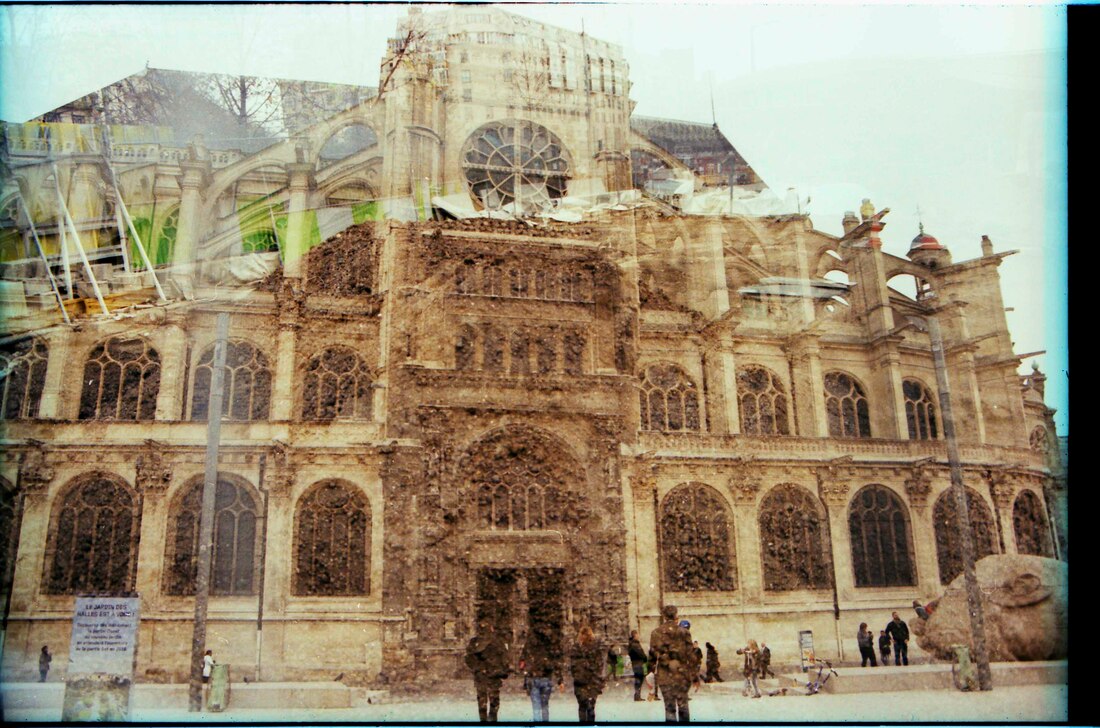

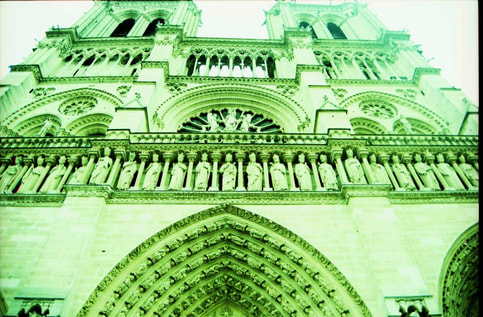

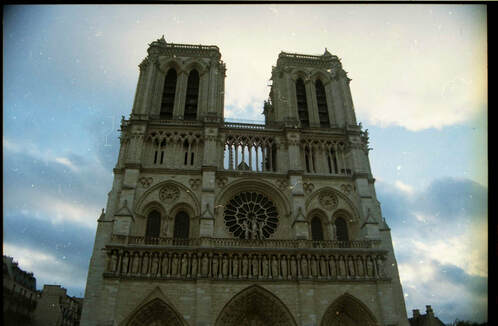

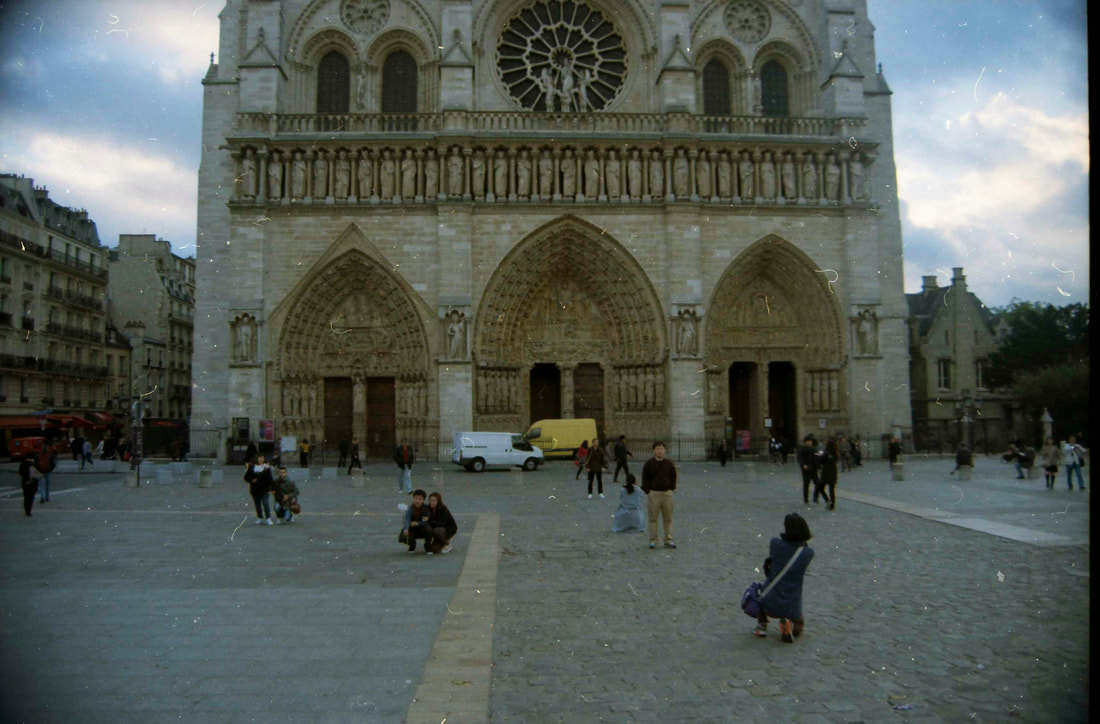

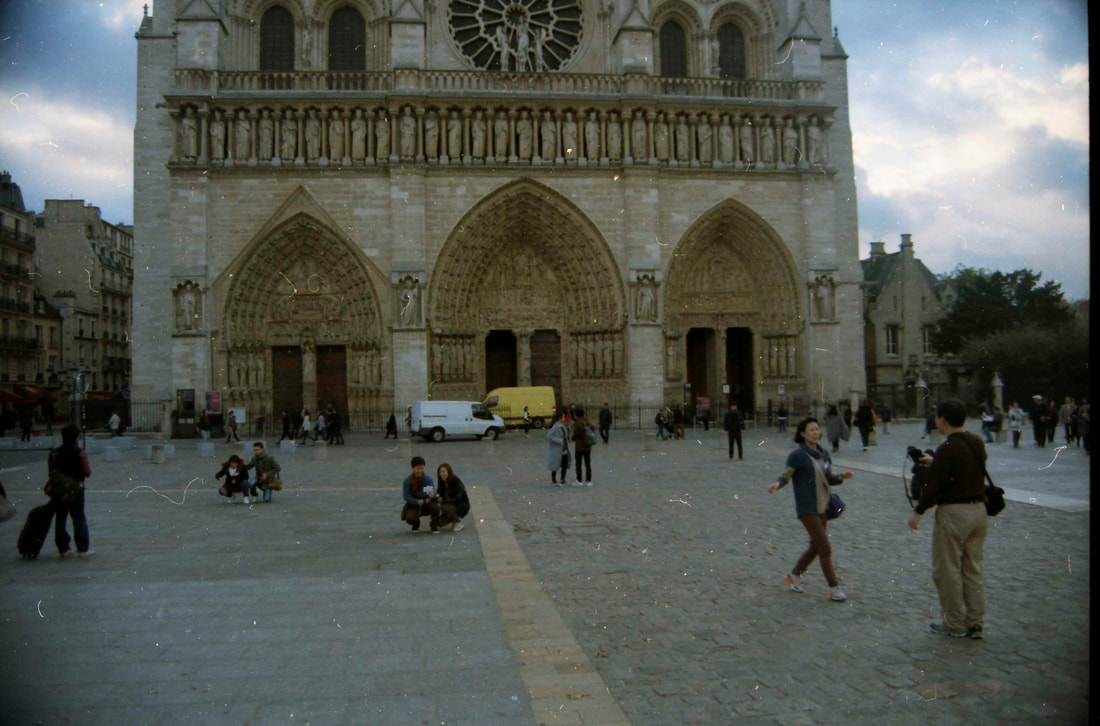

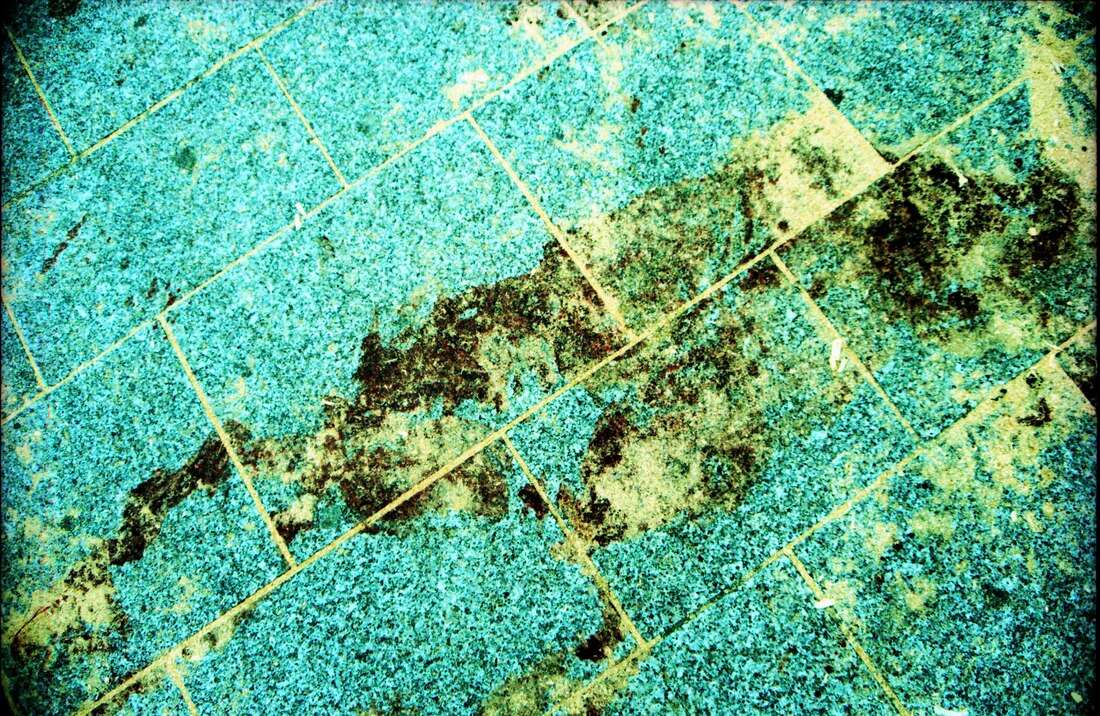

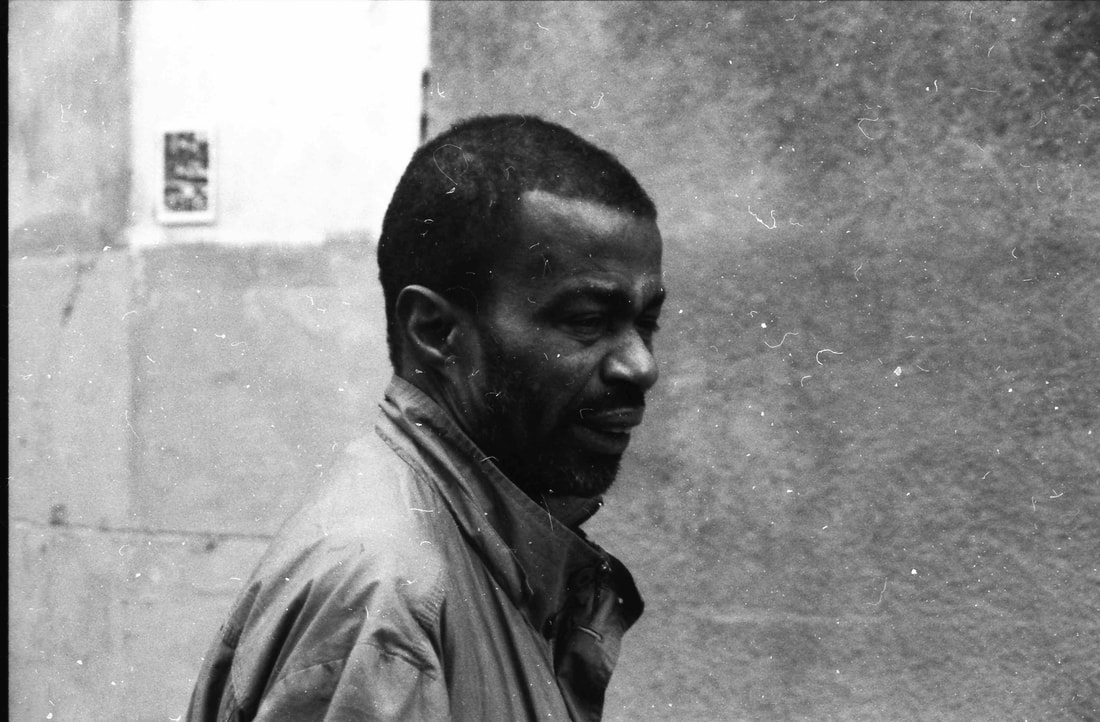

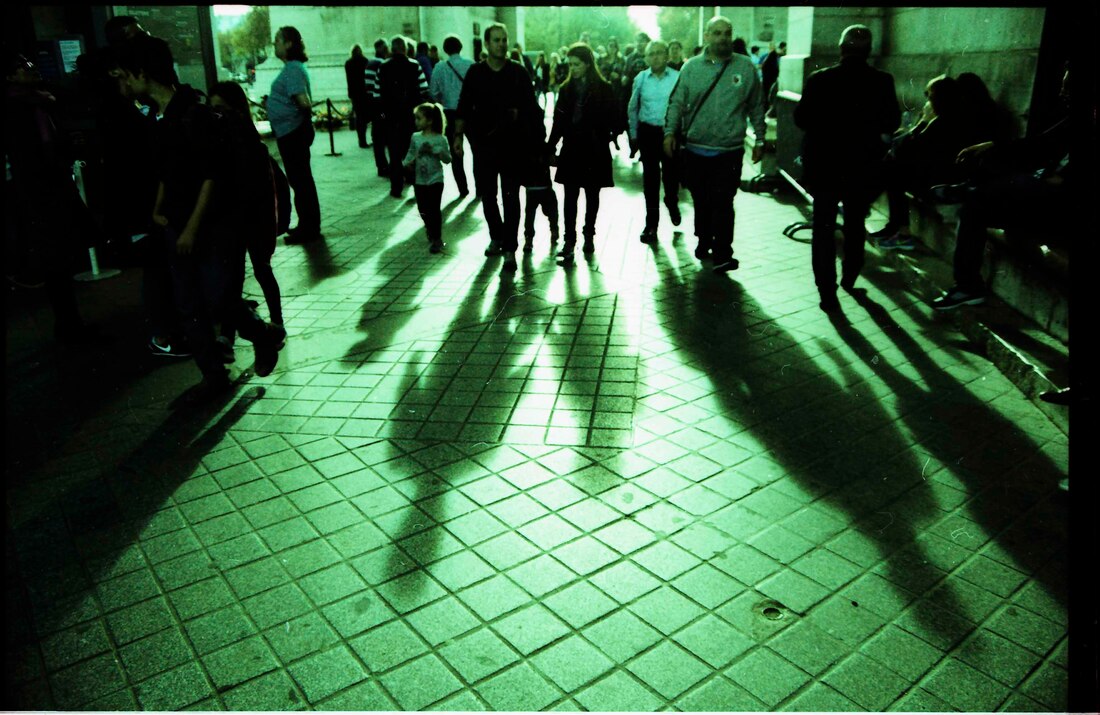

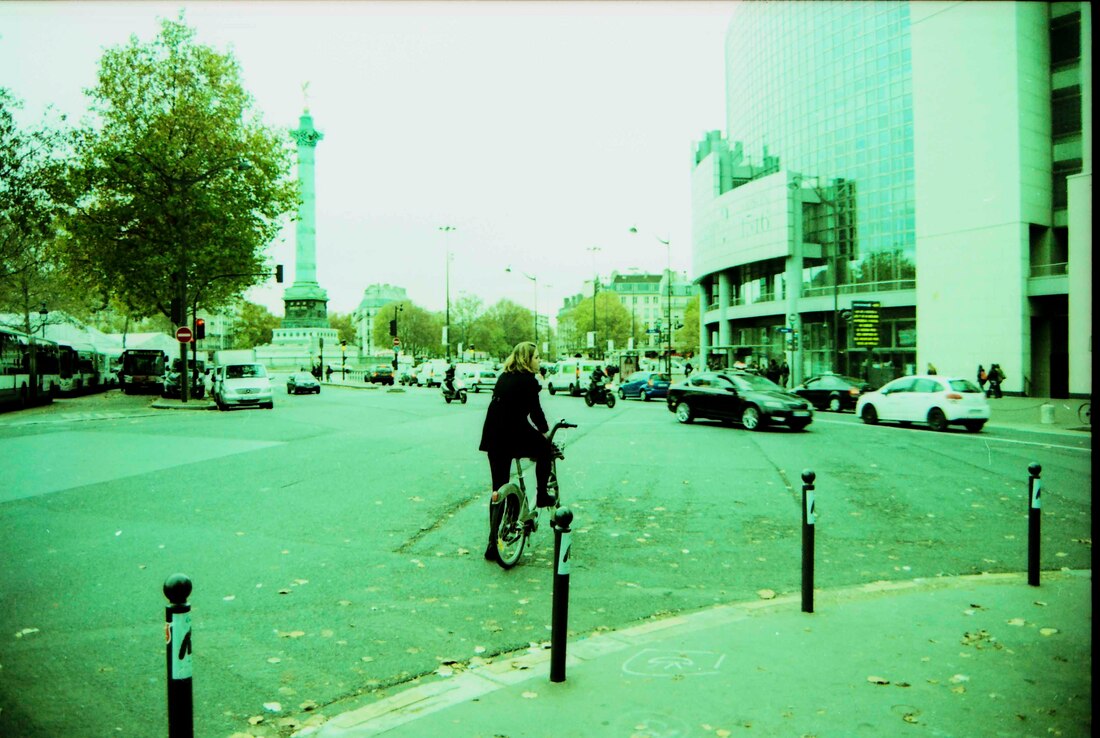

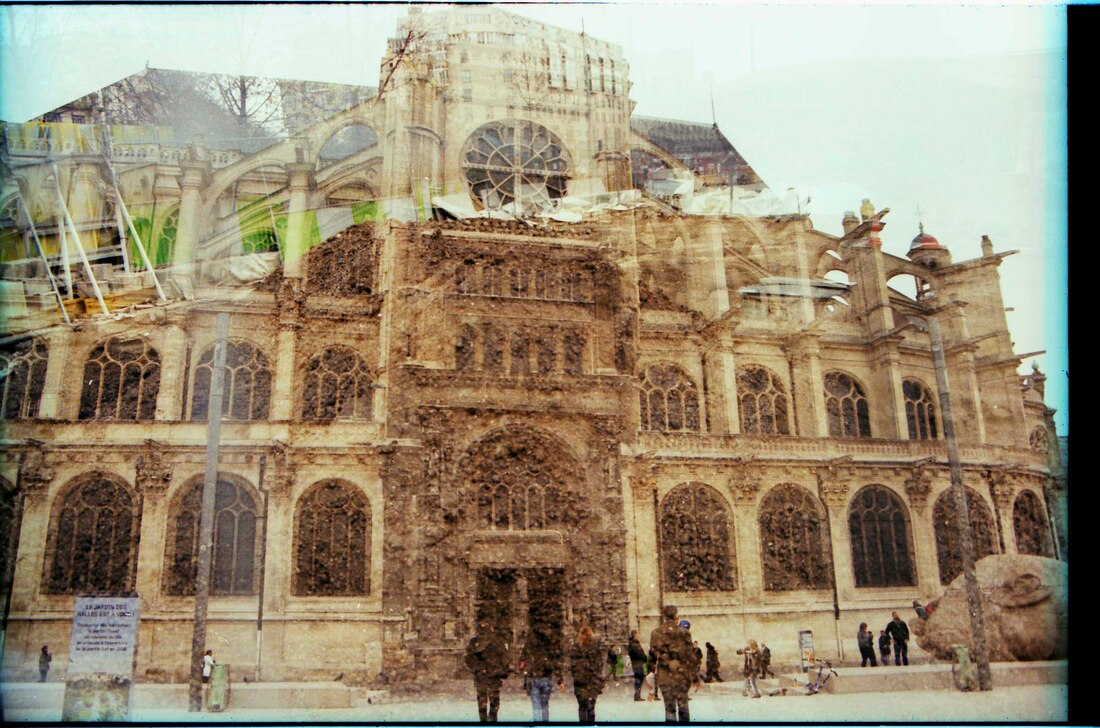

Reposting this 2019 breakdown of the story behind the making of the photograph above, by popular request! Enjoy! This is my favorite photograph I've taken of the Notre Dame. I stood in front of it for a long time before making it. I pride myself in creating images without electronics, that are difficult to replicate, and more importantly, try to capture something of the feeling of the place. The emotion. What did it mean, to stand there, in the days after the murders? I'd gone there in the weeks prior, more than once, usually in the mornings, searching for the right frame– of mind, of light, of mise-en-scene. Everybody with a camera who comes upon that great facade for the first time does this: You just have to. If photography is an act of prayer, this is a gesture of respect toward sheer stupefaction of craftsmanship, the impressive iron stand of art outlasting time. Everyone takes this picture. It accomplishes nothing in terms of actually capturing the mind-boggling sensation of standing beneath all that carved stone, but nevermind. We humans are all living life for the very first time, and you have to cut us some slack for trying. I shot on Ektachrome slide film that I processed in chemicals intended for negative stock ("cross-processing"), the better to get those greens and high contrast; cross-processed film looks great but needs to be delicately exposed. Here I overexposed, as I like to do with color negative, and it just doesn't land. Compositionally, there's depth, sure, but it's missing something. You know it’s missing something because it’s got nothing on actually standing there. Again, no dice. Not really. I'd put the blue filter on the lens in an effort to do something, anything, to get me out of the highly unnacceptable rut of turning architectural treasures into banalities. I was excited by how much happened with the subtle shift in angle; we were moving now. I imagined a slow tracking shot, gliding up the wall. And I'm in love with this lens, a Tamron 28mm, which is slightly too small for my (35mm) Pentax PZ1-P, thus creating the vignettes in the corners. But still. I could do more. I abandoned strong lines and colors and went for a subtler take, involving the surroundings; first the clouds, then the tourists. These are the pictures where you look over them and say, "okay. Fine." Not bad. But not good, either. Abandoning depth, the most important compositional element in the two-dimensional format that is photography, needs to be for a killer reason, and these weren't it. I didn't know how to photograph the Notre Dame because I didn't know what it meant to me. Yet. It was in the days after the massacre that the great facade and its plaza would gain new meaning for me. All of Paris was in shock. As I wrote in the days following November 13, 2015: The tones are hushed, raw, somber, torn. Laughter has been replaced with silence. These are grown men now, with red eyes, ugly from crying but who cares, tears running down their stubble as they point at blood on the ground. You hear the question in every heaving sigh: when did the world stop making sense? We stood there in the hours after. We stood there during the day, and we came back at night. Dumbfounded. That's sawdust in the lower left, absorbing the blood. We stood by, paralyzed. We stopped, those of us who never stop. Those circles on the wall identify where stray bullets are lodged. And those of us who never cry, cried. We cried alone, heaving wet and sticky, broken in broad daylight. Do you know about being alone in the world, like she is there? Or him, defined now not by what is there, but what isn't there, what is forever lost? Everything was different now. Time moved differently; shadows became longer. Even in a crowd, silences were louder than noise: This post is not about Notre Dame. It's about what we were thinking about when we thought the fire would ruin everything. Before we learned they preserved the essentials, that the structure still stands, that no one perished. It's about what the parents of those kids in Las Vegas still think about every night and every day, after the world has moved on and somehow managed to forget about 851 killed or injured, an event that remains low profile because it has no political, religious or otherwise easily blameable motivation. It's about what I think about when I think about Paris. If I had walked the regular way home on November 13, 2015, this would have been the last known photograph: As an image it is not remarkable. Last known photographs never are. Here is the second-to-last: A more aesthetically accomplished composition, but I'm drawn instead to the last one. What does it show? What does it have in common with this man by the Seine, alone with his thoughts on the second day after? Or this girl, also that week, who paused inexplicably in the midst of roundabout traffic, struck into stillness by a thought we’ll never know. Do we only ever really have one thought, at the end of the long day, throughout the turning years? All the myriad inclinations and ponderings, suspicions and reflections unvoiced, as ever pulled back to the original human question: Why? Those two figures are living in the After, whereas my self-portrait snaps were taken before the event. But the mysteries that call to us are the same. This is what we were thinking: Who writes the names of all the days, setting down the joy and the horror we don't yet know we will live? Is there really a wispy figure up there, long on years and maddeningly patient? Or is it the cynic's favorite explanation, a meaningless collision of atoms determining all that is ecstatic and all that is wisdom, a theory as ludicrous as its deterministic opposite? How human of us to guess, to presume we can even comprehend. Might it be something in between? What I know is that I don't know, and the fact of the universe being so much more than what we can grasp... that I find a comfort. Wouldn’t it be depressing, limiting, to know everything? I have seen miracles big and small, alignments and intersections far too sublime to insult by calling mere chance. There's something lurking in the light before memory, that lived in the dawn of our time, that lives within us still, even now. I went back to the Notre Dame. I took comfort in its size, its art, its simultaneous resilience against and embodiment of time. I took note of the surroundings in a way I hadn't before. The quiet reflection of the city was especially potent now, in spaces normally packed but now empty. The absence of tourists made me think back on them. There was an East Asian family I remembered from a week earlier (visible in the "okay fine" photos above), in the plaza, taking photos of each other and the grand facade, skipping about and laughing in a manner both silly and reverent. They would pause, and a moment later the daughter would do a cartwheel. You can sense their happy-go-lucky sensibility in their gestures above. Without succumbing to the myth that tragedy makes people wise (that only happens sometimes), I want to voice the possibility that terrible experiences can open your eyes to goodness in ways you only thought you knew before. You learn the value of things. I now saw how much that family was onto something. You have to laugh your way through this life as much as anything else. I am most impressed by those who conflate lightness and wisdom, playfulness and thoughtfulness in the same breath of their lives, without compromise to either. If there is a hidden presence linking all things, don't you imagine it would approve equally of the Notre Dame's intricate artistic virtuosity... and the giggle in a preteen cartwheel? That there might be as valuable of an answer in her spirited and innocent verve, equally deserving of echoing through the centuries? I like to think so. It was with that in mind that I picked the camera up again, and exposed three times on the same negative. The girl was gone, of course, but I wanted to impose her joie de vivre onto the great cathedral in a way that would let the best things about both attitudes live. It cannot all be somber. There must be movement, energy, and sometimes it won't be sitting there waiting for us to pick up. We have to create it from within ourselves. That was what I could see now, that I couldn't see before. --- If some of the above images are too small to view– here they all are, plus a few extra, in a slideshow:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed