|

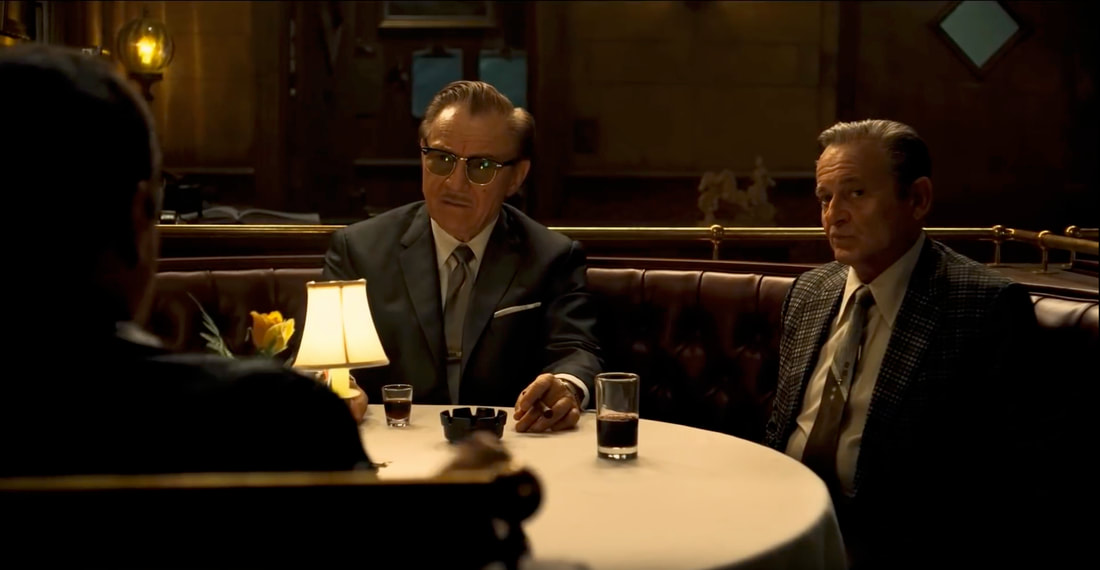

2. The Irishman (I Heard You Paint Houses) "Oh, boy. You don't know how fast time goes by until you get there." With Robert DeNiro, Al Pacino, Joe Pesci et al. Synopsis: Recollections of Frank Sheeran, who claimed to have killed his friend Jimmy Hoffa per mob orders in 1975. Trailer. dir. Martin Scorsese. 209 mins, 1.85:1. Viewers nowadays are so used to being told what to think that they struggle when they’re given the option do so on their own. Not all films have their protagonists helpfully verbalize the themes of the films they’re in, or tell us how to think about their actions. Such things don’t happen in life; people don’t have the self-awareness for it. Can’t a film just say something? Does it have to also say what it’s saying to you? Martin Scorsese’s pictures have always assumed the audience watching them is smart, perceptive, reflective, able to come to their own conclusions very different from what the film’s protagonists may think. His characters are unique in that they usually don’t learn anything. They, like real people, tend to stay the same. They are who they are. We learn a lot, by watching them, but they don’t. Frank Sheeran gets through life a day at a time, up close, using survival skills that got him through the War, but which have crushingly limited value back home in the real world. He became good at following orders, not questioning them… not questioning his own actions. Do you know where that road leads you? As a mob hitman, his tragedy isn’t that he dies prematurely, as most in his profession do; it’s that he survives long enough to live with his decisions. Only after it’s too late do his choices catch up to him, bulldozing his soul over with a regret so vast, so debilitating, he can’t even acknowledge its existence. What they don’t tell you about moral compromise as a survival tool is that it works, in the worst way possible: you survive, and thus have to live with yourself, look at yourself in the mirror, be partner to your past on every sleepless night. The torture of sitting alone in a room, lost to time, aware of the friends and family one could’ve known, could’ve loved, but chose not to. No other mob picture devotes its final thirty minutes to these truths. Scorsese and cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto (they collaborated on Wolf of Wall Street and Silence) shoot on film where they can (why shoot on film?), but any shot requiring digital de-aging had to be photographed digitally, using a complex 3-camera capture system, which has been much discussed elsewhere. The de-aging effect isn’t meaningfully more or less distracting than the other methods of cinematic shorthand for conveying aging that we've all tolerated for years: makeup, or using different actors. Makeup is ideal because it's actual rather than computer-generated, but it's more useful in aging actors up than down. And using different actors destroys continuity in ways that require much more suspension of disbelief than what Scorsese offers here, and that was his principal motive for doing so: these actors know what life was like in the time periods they’re portrayed as living in. Younger generations don’t. They bring that authenticity, as well as an emotional linearity heretofore unarrived at in cinema: the same actors living all the scenes over a half-century lends credibility to their experience, and particularly makes the later scenes all the more potent, rather than just hiring an older actor to pretend the regret of someone else’s earlier performance. It may be imperfect, but for these reasons it beats any existing alternative. Regarding the visuals: this film feels often like a summation and a response to Scorsese's earlier works taking place in related environments. Just as only a younger person could’ve made Goodfellas, only an older mind could’ve created The Irishman. Consider the opening tracking shot, which mirrors the famous Copacabana tracking shot in Goodfellas. That shot emblazoned the high-key vivacious glamour of everything Henry Hill loved about his life, and is appropriately scored to the present-tense joy of The Crystals' "Then He Kissed Me." The Irishman's opener rather shows us the End of the Road, not just of working-class mob life, but of something larger: Life caked over with regret, reflection, and the winsome recognition that the present has gone by, and these are the days of After. The 5 Satins’ “In the Still of the Night,” which accompanies the shot, is redolent with melancholy and memory, which is exactly what The Irishman is all about. I find it a devastating way to begin a film. Consider how DeNiro’s character is musing to us silently, with narration, before he continues speaking, this time out loud. Is he talking to himself, or to a reporter? Or is he silently musing the entire film’s events in his own mind? I like how it isn’t clarified, since it isn’t important: what matters is that he’s thinking it. Note the workmanlike nature of Prieto’s camera: no flashy angles here. We are always either perpendicular or parallel to the action. Says Prieto: “For Frank, he would get an order and then go and do it. So the camera behaves very simply– no spectacular angles or movements when a killing is happening. So the camera pans with him approaching a person, maybe he kills, maybe it pans back. Or sometimes the camera just sat there, static. It even extends to the cars. All the cars, we show them in perfect profile. Filming in a dry, simple, methodical way. There are other moments, which aren’t related to Frank Sheeran, maybe the deposition of Jimmy Hoffa, where the camera moves around, swoops down toward Robert Kennedy.” He and Scorsese chose the appropriately unglamorous 1.85:1 ratio, which Scorsese has used only once since discovering ‘scope in 1991, because, as Prieto told Indiewire, “We chose spherical lenses and a 1.85:1 aspect ratio because the main character approaches his task of “painting houses” (meaning killing people) in a methodical, practical way. It seemed to us that old glass, but without heavy distortion or fancy flares, would be appropriate to represent Sheeran’s perspective.” Prieto also references Garry Winogrand’s wide-angle color work as an inspiration, and has told multiple outlets about the progress of color through the film: a Kodachrome approximation for the 50s and earlier, Ektachrome for the 60s, and a method of increasing contrast while desaturating the image called ENR (like bleach bypass, but variable in terms of how much silver is left in the print; developed by Vittoro Storaro). The level of desaturation increases as the narrative continues, leaning toward monochrome for the bitter end. The Irishman’s power is in what it doesn’t say. It observes, like a silent God, as actions permeate into consequences. It withholds judgment and sees the goodness in ‘bad’ people. It speaks in silences and offhand turns of phrase across a half-century, and it feels, similar to Delillo’s Underworld, like a history of the post-war twentieth century, an expansive plumbing of its ethos and texture and manner of life, neither celebratory nor condemnative but observational. These plebian crannies of existence get their full due here, in lives that aren’t normally considered interesting enough for the silver screen. When did you last see a studio picture about union delegates, delivery drivers, blue-collar backrooms and the drama of unknown working-class midwestern life? Any life seen in enough detail is worth examining. There are multitudes here. Nathan's Films of 2019 Index here.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed