|

No, this post has nothing to do with buses, but I ask you to indulge me. Some of you know that I once wrote film reviews for Erik Samdahl's site, filmjabber.com, when I lived in Hollywood. It's an occupation I miss, and I thought I'd share some capsule reviews here.

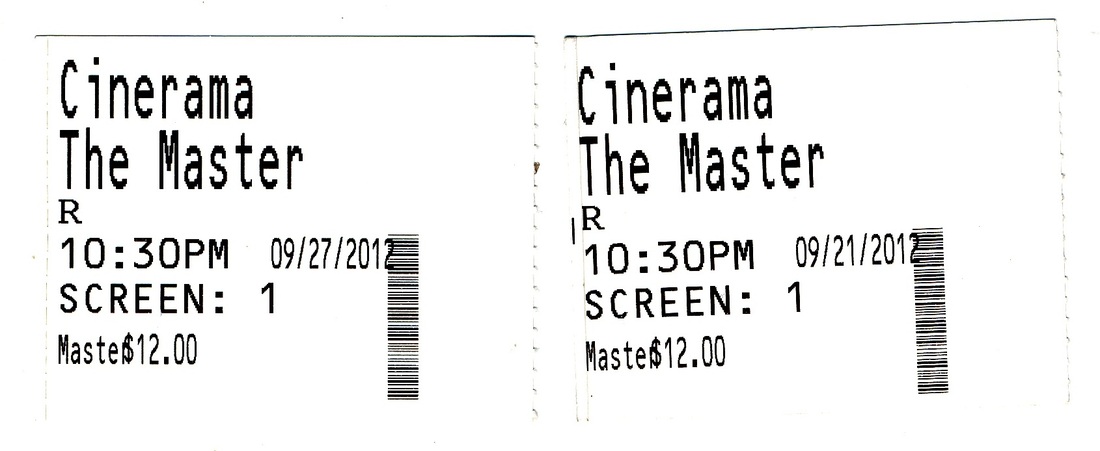

For everyone else, it's 2013, but for us filmgoers, as we finish up with the Oscar-qualifying releases that reach most of the country in January, it's still 2012. With the last serious contenders finally making it to the top 20 cities, I offer my top 10 (actually, 13) for the year, knowing full well the inherent silliness of qualifying value in an art form as multifarious as film. That's part of the fun, after all. I welcome comments as always. This first post is the bottom half of my list, which is thirteen films total, numbered from 1-8. Why the strange numbering? I number lists in tiers; the top three films are all #1, the next two, which I feel are equal but just beneath the top three are both #2, etc. 4. Lincoln (Spielberg) A month in the life of Abraham Lincoln (Daniel Day-Lewis), as he tries to pass the Thirteenth Amendment. Trailer. Some films are greater than the sum of their parts. Lincoln is the opposite. Its parts surpass its whole. There is the Daniel Day-Lewis performance, expounded upon elsewhere, and for which I can summon up no superlative that could possibly suggest the anthemic heights achieved by the man. Day-Lewis' abilities are sublime, as we know from his other work, but to imbue color into a dry figure, to breathe life past our preconceived notions, and above all, to play with dimensionality a decent man- this last tenet is rarer than we think- this, yes, is a miracle of what humans can achieve in art. Acting is one of the two enduring special effects of the cinema- the other being proof of truthful documentation, a la the uninterrupted tracking shot. Acceleration of technology may diminish, but never completely eliminate, the arresting sense of wonder these two miracles engender- and wonder is certainly engendered here, in Mr. Day-Lewis' embodiment of Lincoln. The most surprising thing about Lincoln is that it's funny. Spielberg's pictures have always had a sensibility I find subtly, richly humourous. Recall the bickering of the Mossad agents in Munich, or the banter of lawyers in Amistad. Most people don't know that Spielberg does uncredited rewrites on all his films, and there's a resulting voice that emerges every time; they are filled with an optimism toward human interaction. It's not that the events are always positive; it's that there's a belief that we can communicate. You can't help but smile. Israeli and palestinian freedom fighters arguing over which radio station to listen to, and settling on Marvin Gaye. Matt Damon explaining the Piaf song to the other soldiers. Schindler explaining to Stern that his strength is in "the presentation." It's as if Spielberg believes human connection is positive by virtue of the fact that it exists. There's something to be sad for that. Here, the humor is amplified more than usual, making lively and vivacious the dry texts of history books. The film approaches its titular subject as a human first. Day-Lewis' Lincoln is a warm one, as he amuses himself with jokes and gets carried away telling people stories. We are reminded that people, not ciphers, were alive back then, and their present time was the complicated, frustrating, pulsing present human life we live in as well. The business of passing an amendment into law is told with detail; like Jean-Pierre Melville, Kushner's screenplay has a fascination with process. We feel privy to the minutiae and unseen hassle of procuring votes and completing ideas and paperwork. Complex political concepts are discussed and given time to resonate; Michael Kahn's editing flows at a more relaxed pace than on other Spielberg pictures, giving us the space to revel in the particulars. It's also a pleasure to see Spielberg and his longtime cinematographer Janusz Kaminski using the 2.35:1 frame, something they rarely do. As compared to their other 'scope efforts, the compositions here are reserved in a classical way, incorporating rule of thirds in a stately and unobtrusive fashion. Much of the color is desaturated, for a pleasing compendium of browns and blues; hard light gives a vibrant contrast the images. It's a "thick" image, in the current tradition, filmlike, with deep blacks, and without the brittle falloff of a shortened tone curve. We noted earlier that Lincoln's parts are greater than its whole. The film stands apart in that it can't be called a biopic; it only covers four weeks of the man's life. Its subject is not Lincoln, but the passing of the Thirteenth Amendment, with a focus on Lincoln as its instigator and champion. In this respect the film is brilliant, and so much more engaging than so many birth-to-death biopics of the "greatest hits moments" variety. However. The film occasionally strays from this narrow focus. In the opinion of this reviewer, the film falters whenever it does so. Thankfully, this is really only an issue for a couple of scenes; I'm not referring to the domestic moments with Lincoln's family, which are excellent, but temporal breaks from the four-week period. Steve Soderbergh once said a given scene needs to be told from a chosen character's view; if that's so, from whose perspective is the Grant/Lee scene being shown? Until that point, the film has resolutely been designed from Lincoln's perspective. The break feels odd. Further along, there is a sense of resolution in the moment when Lincoln walks out the door of his house to go out for the evening (to Ford's Theatre); all the film's narrative conflicts have been solved at that point. After that moment there is a shift in focus that makes the remaining scenes feel superfluous. The film is no longer about passing the Amendment, but now simply about Lincoln himself. Kushner seems to feel the need to wrap everything up; consider the decision to portray the Second Inauguration. It's a speech we all know, and everything literalized in the speech has already been implicitly communicated to us through Lincoln's actions during the body of the film. Yes, the film's recreation of that event and similarity to photographs is shocking in its accuracy (interestingly, nearly all the actors playing historical figures look uncannily like their real-life counterparts); as yet, however, I found it fitting not as a conclusion of the narrative, but only as a wrap-up coda at best. And perhaps that is what Mr. Spielberg intended. Having expressed those qualms, I'm compelled to repeat this very good film, this excellent film, flawed though it might be, still towers over the accomplishments of so many others. It's a qualm from a first viewing only, and I don't want to imply that the film is something other than brilliant. It is. It contains pleasures you won't find elsewhere. 5. Silver Linings Playbook (O'Russell) A young woman (Jennifer Lawrence) helps a borderline bipolar man (Bradley Cooper) move on from his divorce. Trailer. What surprises about Silver Linings is its energy. It establishes a high bar early on, and it stays there for the duration. Here is a film not about the wealthy, or the poor, but about all of us in-betweeners; refreshingly, it isn't another movie about people who live in oversized condos in Manhattan, working jobs and hours that could never support such a lifestyle. No, we're somewhere in the midwest, where the characters live in generic houses and drive entry-level sedans from 15 years ago. This fascination with the working class- apparent also in O'Russell's last film, The Fighter- appeals to me greatly. There is also the film's tracking of the psychological shifts in the protagonists, and the exploration of moving on- something everyone wishes they could do a little better than they can. It's a film that feels eminently relatable, and the humor derives from real life. It slips easily into the moniker of "feel good film of the year," but it does so with heart, and truth. To watch these two grapple with their problems and themselves, finding what they need in the other, is exhilarating and fun. It's a rejuvenating experience. 6. End of Watch (Ayer) Day-to-day life of two Police officers (Jake Gyllenhaal, Michael Pena) in South Central LA. Trailer. End of Watch is the best cop film in many years. It does something most cop films don't do: it doesn't give its protagonists a solvable problem. It simply follows the workaday tribulations of two beat cops as they negotiate the quivering hellhole of South Central. I think this is a masterstroke, because it goes a long way in conveying the mental process of being a cop: you are constantly confronted with problems, serious ones, whose resolution you never see. There is no discovery that makes everything right, or a takedown of a baddy that shows justice reigns in the end; there is simply call after call of awful, disgusting human behavior. Your efforts as a cop to make things right are so incremental or inconsequential that they seem pointless. In Seattle we sometimes marvel at the way cops treat the people; but can you really blame them, when they're confronted with this skewed, terribly selective view of humanity every day? I'm making the film sound like a tough, depressing slog through a nightmare. It isn't. It's an adrenaline rush. It's a celebration of the resilient attitude of our two protagonists, in that it dares to place them in realistic situations and trajectories, and watches as they handily retain their exuberance. The world hasn't worn them down just yet; it may in the future, but for now, their energy is unstoppable. The film doesn't force them into a contrived murder mystery; it's too realistic for that. It's simply a portrait of life. Ayer's screenplay gives them room to live; sometimes we simply follow them around in their cruiser, listening to the two of them talk, argue, and joke about life. These are the sorts of conversations you have with your pals, and this film allows for that sort of reality to slip in. The dialogue often sounds improvised, but Ayer says 99 percent of it was written. He lived in the area, as I have, and has an ear for the way people speak. Having spent much time around West coast "ghettospeak," it's refreshing to hear it used so accurately here; one doesn't realize how rarely it's realistically incorporated in film. My only qualm is the level of violent imagery. My sensitivity to violence grows as I get older. It is appropriate for the film, however. The most offensive sort of onscreen violence in movies, in my view, is when things are either sanitized (a la Bond), or reveled in (a la 'gornagraphy'). When a film is attempting to convey a way of life, or a historical event, however, realistic depictions are needed. As such, it makes sense here, but viewers should be forewarned; it is leery in a Grand Guignol sort of way, as in a waking nightmare. 6. Cloud Atlas (Wachowski sibling duo; Tykwer) Narratives spread across time and space, connected by theme; loosely follows an ascension in the moral aptitude of one man (Tom Hanks) over millennia. Trailer. Like Anna Karenina, I was the only person to go see Cloud Atlas, and it seems as if Roger Ebert and I are the only people who like it (read his review here). It's unlike any other, it's beautiful to look at, it's drenched in thought-provoking ideas, and washes us away with its dreamlike connections and atmosphere. I, for one, loved it. In what other time in film history could we expect to see a film this radical distributed by a major studio? Ignore the naysayers. We are living in an excellent period for film. It's not the Eighties anymore. The riffraff will vanish over time, but there are many works from now which will endure. This may not be one of them, but it certainly deserves to be seen. The trailer gives a fair idea of the experience of seeing the film- a bunch of stories using the same actors in different roles, implying a continuation of souls across time. Any given scene is easy to comprehend; it's the connections between narratives that puzzle. I suggest watching the film without trying to figure it out. It leaves you with an overall feeling of deeply founded optimism, and the romantic belief that there is goodness in people, and that the germ of that goodness can thrive through the centuries. 6. Killing Them Softly (Dominik) About ten ten-minute vignettes, mostly conversations between interconnected men involved in low-level underworld crime (with Brad Pitt). Trailer. This has been the year of me seeing and loving films that nobody else likes. Killing Them Softly, based on the 1974 novel Cogan's Trade by George Higgins, is the latest effort from Andrew Dominik, whose achingly beautiful The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford remains one of the best films of its decade. No one saw that one either. Whatever you're expecting, Killing isn't that; the film starts off and we settle in, realizing this movie won't really be about Brad Pitt, or any other single individual, but more about the politics of crime and business in America, by way of a series of gossipy one-on-one conversations between men. It might sound scattered, but it feels of a whole; the ending is perfect, bringing home a point with impressive clarity. The film makes some rather pointed comments about politics, and on a broader plane of thinking than we might be accustomed. In terms of form, viewers of Jesse James won't be surprised to hear that the aesthetic decisions are unparalleled. Photographically the film has "a technique so sophisticated that it verges on the precious," writes The New Yorker's Anthony Lane. He is correct. Each shot is beautiful, and many of them are doozies; it's shot like nothing else I've seen. Witness the macro lens on Ben Mendohlson's face as he trips out on heroin; or Pitt crossing the frame laterally while fireworks explode behind him, shot with a telephoto lens whose obscene length I don't even want to guess at. There is also the car crash, a slow-motion ballet of raindrops and blood, cut with a sublime kineticism. The music cues are choice as well, making the film an aural and visual treat. Once again, the violence is perhaps slightly too effective at communicating pain; the film delves into detailed excess in whatever it's exploring, whether violent acts or monologue. It is always and completely about whatever the scene is about. Who could argue with that? 7. Rust and Bone (Audiard) A romance between a whale trainer (Marion Cotillard) who loses her legs and a bare-knuckle fighter (Matthias Schoenaerts) struggling to raise a child. Trailer. This is a problematic piece. It's the latest from Jacques Audiard, whose Un Prophete (2009) is one of the better films of our time; Rust is similiarly dense with material, juggling a lot of themes at once; there's enough in here for several movies. It's about a woman recovering from amputation; the struggles of single fatherhood; poverty in lower-class France; ethical workplace security considerations; Eastern European male attitudes towards women; the realization that other people carry greater importance than oneself; defining oneself through one's body; the intersecting ways in which damaged people can fill each other's needs. And that's just off the top of my head. The Cotillard character, injured early in the film, needs someone who looks past her deformity. Schoenaerts supplies that. He is a brute of sorts, and he goes through a mental awakening at the end akin to what she experiences earlier in the film, realizing what is important to him. They are "wounded birds," as a friend put it, and both experience bruising change; there is a focus on physicality and pain and the resulting healing- both physical and mental. Schoenaerts' wounds at the end closely mirror Cotillard's at the beginning. There are a lot of Beauty and the Beast parallels here, and I look forward to parsing it out further on future viewings; there really is too much going on here thematically for me to intelligently discuss after only a single viewing. The ending is baffling; I want to believe the literal meaning of the image, but have difficulty believing it. Is Audiard suggesting the opposite? I hope not. Knowing he is a filmmaker who thinks everything out is refreshing, in the manner of Fincher or Mann; it encourages the viewer to consider matters deeply. It is all intentional. A note must be made about the visuals. After the claustrophobic world of the prison in Prophete, Audiard mentioned a desire for the opposite in his next film, here- expansive wide frame and bright, light color. The soundtrack pops with vibrant mixtures of every type of music conceivable. At least aesthetically, there can be no argument as to the film's ravishing competence. And of course, the performances by the two leads are nothing short of amazing; both impress equally in very difficult roles. I never tire of watching Cotillard, who can suggest so much with so little. Notice her expression as she watches the dancers in the club, doing so easily what she can never do again; the mixture of admiration, envy, and frustration, writ so subtly, and yet so palpably. Honorable Mention: 8. Magic Mike (Soderbergh) A mentor-protege narrative in the world of male stripping, from the perspective of the mentor (Channing Tatum). Trailer. Yes, that Magic Mike. How many mentor-protege stories sideline the up-and-coming protege to focus on the psychology of the mentor? None, that's how many. Magic Mike is one of those films that's impossible to sell- you'll invariably bring in the wrong audience. Consider this logline: Channing Tatum male stripper movie, co-starring Matthew McConaughey with his shirt off. That sets up one kind of expectation. Film about Channing Tatum's own experiences as a young male stripper in Los Angeles. That sounds a little more grounded. Introspective, meditative mood piece directed by Steven Soderbergh about a man reorienting the priorities in his life. The trouble is all of these descriptions are true; but it's the last one that carries the appeal for me. Who knew you could make a meditative, thought-provoking male stripper film? It's a unique piece. Soderbergh is customarily distant from his characters in terms of emotional relatability, but the film is likely his most accessible since Traffic (2000). It goes without saying that this is Tatum's best performance, and there are indications of substance under the veneer of the character that intrigue. He craves depth and connection, and people around him don't see that. A female friend who teases out this side of him ends up being central to the story. The decision to focus on the teacher and his problems instead of the familiar young-apprentice-as-underdog-hero is refreshing. Ebert's mantra says that a film is not great because of what it's about, but because of how it's about it, and Mike serves as a stark example. Soderbergh's unemotional approach allows the ridiculous environment to be taken seriously, and his camera, as ever, is on the experimental side, bathing scenes in yellow golds, holding on unexpected compositions, and cutting conversations in interesting ways (he has a tendency to focus on whoever's not speaking). There's a killer moment toward the end when the camera holds on Tatum's face as he silently makes a crucial decision, and the understated nature of the moment is fantastic. it reminds me of an oddly similar moment in Paul Thomas Anderson's towering Boogie Nights, when the camera holds on Wahlberg for over a minute as he realizes what he's done with his life, and that he really, really needs to get out of Alfred Molina's house. Mike is not as good as Boogie, but I recommend it if you warmed to that film. Six films remain; I'll post them soon!

2 Comments

|

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed