|

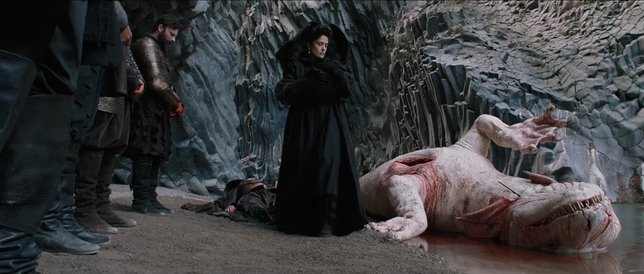

"You don't want love. You want a love experience." Here we are at the final five. If you're wondering why there's film reviews on a bus driving blog (!)– I worked as a film critic once, in my former life living in Hollywood. Somewhere online you can probably still find articles of me bashing 300– but we don't read about that one, especially with all these lovelies to pore over.... This is the fourth & final post in this series. For those of us late to the party: Part 3 (films 6-10), Part 2 (films 11-15), & Part 1 (Nathan weirdly justifying that it's a good idea to watch Deepwater Horizon, among other honorable mentions). Without further ado! Image courtesy A24. 5. American Honey "Do you have any dreams?" Directed by Andrea Arnold. With Sasha Lane, Shia LeBeouf, et al. Synopsis: A wayward teen girl joins a band of misfit youths as they travel the midwest selling magazine subscriptions. Theatrical Trailer 1. Sometimes a film explores a topic so definitively, with such magisterial scope and detail, that all other films on the same subject are forced to stand in its shadow. Think Schindler's List for the Holocaust, or JFK for the Kennedy assassination. Saving Private Ryan for WWII European theatre. Other films may be made on these subjects, but they are forever doomed to be subsidiary in some sense, and they need to be specific to hold their ground (Son of Saul stands as a worthy Holocaust picture in its unique approach and minutely focused subject matter, for example). American Honey is one of the giant pillars. It will forever stand as the end-all, be-all portrait of what it means to be young, white, poor and uneducated in the American midwest. Since the majority of America's poverty is by far rural white poverty, and the midwest is the topographic majority of America's land mass, American Honey in some ways can considered to encompass certain dominant aspects of the American condition at large. It is monolithic in scope and simultaneously very intimate; is almost three hours; throbs with life and color and music; is more interested in watching its characters live than teaching them lessons; doesn't have a three act structure, doesn't have much of an ending, and is as rambling and directionless as its characters' lives are… if these elements intrigue you instead of turning you away, you're in for a treat. Read (way) more of my thoughts on the film here. Image courtesy Shout! Factory. 4. Tale of Tales (Il Racconto dei Racconti) "Every new life calls for a life to be lost." Adaptations of stories in the Pentamerone (1636), the first written anthology of fairy tales. Theatrical Trailer (US). Based on the oldest recorded collection of solely ofl fairy tales, Matteo Garrone's latest is a departure from the bleak masterpiece Gomorrah and its underrated follow-up, Reality. Here is a visually resplendent, fully realized world, a film of scope and richness we associate with big-budget historical studio spectaculars– except here, incredibly, no concessions to demographic pandering are made. The best art pieces nudge us beyond our comfort zone– how else, after all, are we to expand our perception? Garrone guides us through the baroque and grotesque with sure-handed delight, involving the viewer in a series of timeworn, universal dilemmas involving kings, creatures, princesses, promises, desires, and bonds of several kinds. The stories may be dark, but possess that invigorating sense of rapture we feel when reading fairy tales. On the strength of its craft, depth and structure, this is absolutely and incontrovertibly the best serious fantasy/fairy-tale picture yet made. Image courtesy Paramount Pictures. 3. Silence "No man should interfere with another man's spirit." Directed by Martin Scorsese. With Andrew Garfield, Adam Driver, Liam Neeson, Ciaran Hinds. Synopsis: A Jesuit missionary struggles with the meaning and purpose of faith during the 17th century purging of Christianity in Japan. Theatrical Trailer. Thoughts to ponder while taking in Martin Scorsese's latest, wildly underseen new masterpiece, an adaptation of Shusaku Endo's 1966 novel (the film wasn't completed until the last minute, and despite excellent reviews never found an audience nor an Oscar presence, mostly due to the lack of time needed to mount an effective marketing campaign. If you're looking for a gem that fell through the cracks, this is it):

Image courtesy A24. 2. Moonlight "Who is you, Chiron?" Directed by Barry Jenkins. Synopsis: A quiet, introverted young man struggles with expressing himself and his sexuality in the hostile environment of Liberty City, Miami. Theatrical Trailer. Much has already been written on this delicate, sensitive gem elsewhere. I'll be brief. One of the year's most formally sophisticated entries, it deftly uses old film lenses, narrow depth of field, unusual color correction, and refreshingly unexpected musical choices (Face it. You've never heard a major cello octet in a movie about Miami ghettos) in order to convey the experience of a largely inarticulate young man as he struggles with how to express himself and his passions. Films about introverts are harder to make, and lives like Chiron's have so rarely had a place in cinema before. The Best Picture win is a watershed miracle for this reason alone, on top of overcoming concerns that it's "too black," "too gay," "too small," doesn't have stars, and more; at a $1.5m budget, it's the cheapest film ever to win the top award. The last two scenes (diner, apartment) destroy me. The care and love as Kevin prepares the meal, his unwillingness to give up on his belief in Chiron's suppressed but beautiful character; the honest self-awareness and double meaning of Chiron's last line. If film is the great empathy-building machine of our time, this is required viewing for all Americans. Image courtesy Broad Green Pictures.

1. Knight of Cups "[B]ecause I stumbled down the road like a drunk... that doesn't mean it's the wrong one." Directed by Terrence Malick. With Christian Bale, Cate Blanchett, Natalie Portman, et al. Synopsis: A well-heeled Hollywood screenwriter searches for direction after realizing achieving his ambitions isn't the answer to happiness. Theatrical Trailer. The ultimate extension of cinema lies beyond narrative. Film is a great medium for telling stories, but it can do much more. Actors performing well-written lines is the province of theatre. Cinema has the ability, with its preponderance of image and sound, to be far more potent. It has no need to reduce experiences to words, no burden to simplify life into discrete units. From day one it held the promise of something bigger, deeper, larger. The earliest films reveled in the power not of the word, of course, but of the image. Take a look at Dziga Vertov's Man With a Movie Camera, the legendary 1929 film from which it's been said the origins of all stylistic innovations in cinema can be found, but which more importantly captures the vitality of life experience without the need for a plot. You don't need story. You have life, and isn't life, after all, what happens in between? Let Knight of Cups wash over you. Don't try to figure it all out. It's bigger than that, designed to reach you on a level beyond the intellectual. The cavalcade of stunning, entirely natural light-lit images gradually cohere into something whole: a successful Hollywood screenwriter (Bale) slowly realizing that the status of material success, long his aim, has not answered his search for fulfillment. We set goals, convinced achieving them will bring the fulfillment we dream of. What do you do when you get there and discover they don't? There's something more. It was always nearby. That delicate something is what this film is about. Bale wanders through L.A., as we do through life, contemplative and observant. The camera matches his ruminative inquisitiveness, careening around people and drifting through rooms and highways, seeing beauty everywhere, photographing light as a character, as though there was a silent, benevolent presence in our lives, always just around the corner, waiting. Bale's journey toward substance and purpose, and the pearls of wisdom he gains from each of his relationships, profoundly move to me, not least because the film uncannily mirrors journeys of my own in L.A. Also particularly gratifying to me are how Malick, in previous films largely a purveyor of beauty in the natural world, shoots L.A. with just as much verve and celebration, as though its concrete expanses were no less ravishing than the quiet hills surrounding. It's all about our perspective. His L.A. is no den of purgatory, but as ever a place where beauty is visible by those with eyes to see it, where a thoughtful calm can read the signposts all around, guides toward a higher plane of being. What other filmmaker would cut from le Jardin de Luxembourg to a drive-in burger stand in Bartlesville, Oklahoma with no apparent judgment? Who would see the same beautiful light in both places? You can understand why I like this guy. As well, the same generosity of perspective is applied to his characters. It isn't only Blanchett's doctor or Portman's affluent wife who are the arbiters of wisdom in this picture, though they might have the more apparent intellectual capacity. Look at Teresa Palmer's stripper, whose grasp of the ephemerality of substance in Hollywood is grounded and acute ("real life is so hard to find"), or Imogen Poots' aspiring starlet, who has no status or material accomplishment to her name, yet in a sentence recapitulates Bale's entire philosophical struggle. The film may take place in Hollywood, but it is not of it. Most complaints about late-period Malick involve critics wishing the films were more comprehensible, more digestible, plot-driven… basically, more ordinary. I say revel in the differences. It's too unlike other films to be judged by their standards. You've never seen photography this dazzling, a camera this sensitive, this untethered, interior monologue this private. It's a film about the issues we all think about, but rarely speak aloud. That's that! Thanks for reading! ---- -Some of this may sound familiar: I recently raved uncontrollably about Malick's latest, Song to Song, which is the third in an informal trilogy of films, following Cups. -Terrence Malick’s “Knight of Cups” Challenges Hollywood to Do Better: Richard Brody eloquently expounds on Knight of Cups, something of a lone wolf in the face of the generally dismissive reviews it received. -8 Reasons Why “Knight of Cups” Is Terrence Malick’s Best Film So Far

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed