|

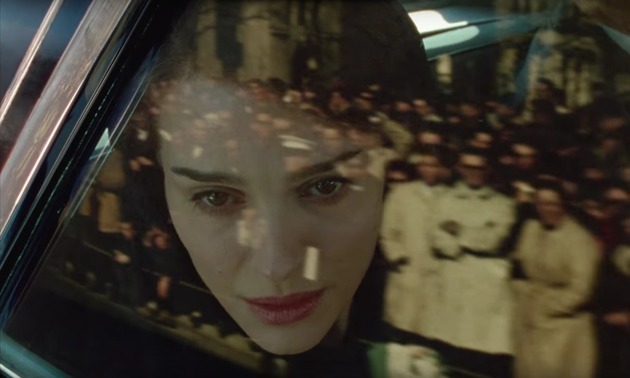

"The people who help you, they might not be who you thought or wanted. They might just be the people who show up." --- I make this list so you don't succumb to the strange but powerful desire to rewatch Scary Movie 5. Your life is important, and so is your time. I'm doing this out of love. Friends let friends know there's films besides Children of the Corn IV and the Ghost Rider franchise which might resonate. You read the previous post, which began a list of counting down from fifteen. This is films ten through six. Don't take the numbering seriously; I can hardly bring myself to order these things. I got so excited writing about Jackie that I almost bumped it halfway up the list; then I got even more excited about 20th Century Women, as you'll tell from my wildly rhapsodic evaluation below, in disbelief that I had it at a mere #8 instead of a more appropriate #1… before realizing I just really love films, and this year was a lil' too good to be true. Image courtesy Fox Searchlight. 10. Jackie "I lost track somewhere, what was real, what was performance." Directed by Pablo Larraín. With Natalie Portman, Billy Crudup, Peter Sarsgaard, John Hurt. Synopsis: Jackie Kennedy struggles with how to conceive of death, life, identity and loss in the days following her husband's assassination. Teaser Trailer. Let's start with what the movie isn't. It's not a biopic covering a "greatest hits" parade in Jackie Kennedy's life. Nor is it a linear depiction of the assassination from Mrs. Kennedy's point of view. We know the events of her life, and we know the assassination. This is an interior portrait. It's abstract. In times of grief, we struggle to get a handle on things, and similarly here, we watch not a story but a collection of felt moments. Depth of emotion is what links the thread from scene to scene. It's why it makes sense to cut from a Life Magazine interview to Dealey Plaza to an airplane bathroom. We don't think in order, after all. When we grieve, we're not grounded in reality; we face instead a ghost, the haunting mass of an absence which pushes everything else into an elliptical periphery. Larraín's film seeks that elliptical realm. It's a deliciously challenging watch. The Oscar-nominated score is a boldly imposing modernist classical, half dirge, half Jonny Greenwood, a stark contrast to the heavily featured Camelot musical tune; Larraín's use of the rare Swedish 1.66:1 aspect ratio and choice of 16mm film takes us outside of the normal "biopic"/period cinema environment. The editing reaches an apotheosis at a point when four time periods are simultaneously intercut, and we're able to follow the emotional trajectories in each situation and appreciate how they reflect against each other. It's heady stuff. I loved it. In a daring move, Larraín takes us inside the car during the moment of the assassination; through cinema history, all movies on the subject have always stayed outside the car, never venturing closer than the Zapruder film does. Here, the immediate and ugly banality of death is shocking all over again, though it is a death we have seen before, but now we're alongside her in the seat, and more than ever we understand this loss was most of all, for her, a violation. The American visual lexicon of that hyper-studied moment has been expanded here. This isn't the only film about loss on my list, but it was probably the most impacting. I've been thinking a lot about grief, and Jackie is instructive in its appreciation of the value of creating narratives to understand the losses we sustain. An exchange like this could only have been written by someone with a too-close understanding of lamentation: "Take comfort in those memories." Stories help us understand, allow us to live with ourselves and move forward. Jackie's courage in developing a narrative, alone, is rightly the focus here. There is so much to learn about loss and selfhood by watching this picture, aside from the already fascinating explorations of Jackie's preoccupation with legacy and determination to assert herself as more than shallow. Of indescribable value to me are John Hurt's words on how we carry forward– too delicately powerful to state here out of context. Just go see the film! Worth noting as well is the speech and manner of the characters. These are people who came of age in the forties, and their diction, air, and politeness are not of our time. People thought differently back then, and for all the great progress being made today, there are great things to be learned here too. Image courtesy Vitagraph Films. 9. Aquarius "So when you like it, it's vintage; when you don't like it, it's old. Is that right? You guys don't know what it's like to feel crazy without being crazy and that the madness is out there, don't you?" Directed by Kleber Mendonça Filho. With Sonia Braga. Synopsis: A vibrant, strong-willed older woman fights to keep her apartment. UK Trailer. The most exciting thing about Aquarius, and there are many, is that the film at large convincingly posits the idea that the high point of dynamic, pulsing vitality in your life can be in your mid-sixties. And not just your mid-sixties, but your mid-sixties as a widow, living alone, and on the verge of losing your home. I'm reminded of the line at the end of Herzog's Stroszek: "So. your car's kaput. And your girlfriend is gone, and thine house they have sold. [pause] I wouldn't worry about it." Clara, Sonia Braga's character, isn't nearly as happy-go-lucky, nor does she face as much tragedy, but she's filled with an energy to act that must come from somewhere, and the urge toward action is a creative urge, and therefore ultimately a positive one. She's a fighter. Winning is interesting to her, but it's not as interesting as just fighting, and fight she does, for all 146 minutes of this gigantic, hugely enjoyable portrait of a movie. Sonia Braga was a sort of "Sophia Loren of Brazil" in the 60s, and she manages to look as radiant here as she ever did, decades later. Her character understands that the aging of the spirit has little to do with the body. We grow wooden when we stop being curious, humble, open to new ideas; when we lose our sense of wonder. The prologue shows Clara as a young woman attending the birthday party of an elderly female family friend, and we assume it's from here she learns how vitality doesn't need to decline nearly as quickly as our vessels do. I feel a sense of deep, profound optimism watching this picture. UCLA professor and cultural anthropologist Jared Diamond wrote in his excellent The World Until Yesterday that he believes his late seventies are the high point of his life so far. Clara might say the same about her sixties, if she weren't so busy partying with her friends and sabotaging the sabotagers of her apartment. This one's a gem, and despite its acclaim elsewhere you won't hear it being talked about much. Seek it out, and spread the word! Image courtesy A24. 8. 20th Century Women "Look. Wondering if you’re happy is a great shortcut to just being depressed." Directed by Mike Mills. With Annette Bening, Elle Fanning, Billy Crudup, Greta Gerwig. Synopsis: An adolescent boy growing up in 1979 Santa Barbara is shaped by the women around him. Theatrical Trailer 1. Some films feel like they contain the totality of life experience in a certain place and time. In its intimate specificity, this film feels universal. My first years on this earth were in Southern California, and in the mid-eighties the visual vernacular of the previous decade was still very much in evidence. Orange and brown, pencil sharpeners in the corner, waiting by the phone. The world hadn't been digitized yet. You had to be a little more proactive, a little more skilled, and a lot more patient. Life in the Twentieth century, more than now, was something you could touch. As adults we forget how miserable much of growing up is. Yes, children are exceptional at being happy, but the notion that they always are is a myth we oldsters have made from our fondest memories, which thankfully loom larger than the others. Recall that an enormous amount of youth is spent feeling intense longing, loneliness, and frustration. But there is such color, too, such immediacy. We hadn't distracted ourselves out of the present yet, and we knew how to feel, how look out at the world with wonder. Bening is a force of nature here. Her mother character, at once too young and too old for the shifting social mores around her, is elusive. We never fully know our parents, and in like fashion, Bening is right there, and though she's fully drawn, she's always just beyond our complete understanding. Elle Fanning is another highlight in the already stellar cast, and Mills advances the "mixed-media" approach he began in Beginners, this time incorporating not just stock footage and stills but text in a very pleasing way. 20th Century Women feels like a certain place, a time I somehow feel I know well. Maybe in its carefully observed humanity every viewer will find something similar, but with my circumstances I feel especially close to the picture. It unfolds as life does– a story only in the most general sense, more a slowly coalescing accumulation of moments, the most offhand and the most pivotal, the makings of memories we didn't know would become formative. Like Mills' previous film Beginners, there is such wisdom in the lines here, but this times the lessons are deeper, more richly filled in. It is so far beyond your average coming of age movie ("after that summer, they would never be the same," etc etc). You walk out of this trying to remember certain lines, without the wisdom of which you would feel bereft of something. Image courtesy Paramount Pictures. 7. Arrival "If you could see your whole life from start to finish, would you change things?" Directed by Denis Villeneuve. With Amy Adams, Jeremy Renner, Forest Whitaker. Synopsis: A linguist (Amy Adams) is asked to help translate communications from alien life forms. Teaser Trailer. Arrival has the nerve to start off being about an alien invasion and then end up focusing instead on human emotions, motherhood, and loss. The picture is something of a miracle, developed largely outside the studio system (it was turned down by several majors who insisted the main character be turned into a man), as engaging cerebrally as emotionally. Most large-scale films, due to their high costs, have to appeal to a broad demographic at the box office to recoup their expenses. This one is refreshing in its refusal to do so. If you give audiences dumb movies, they'll lower their intellect to match, and if you give them heady material, they'll rise to the occasion. Which is more interesting and pertinent, after all? Imaginary alien invasions, or how language shapes the way we think and understand time? What we would make of our lives if we could see them in totality? Isn't memory something like this, as concerning our journeys thus far? The answers Arrival comes up with I find deeply comforting. Also worth noting is Villeneuve's customarily precise use of the camera. Like Fincher, he avoids handheld at all costs, instead favoring highly controlled, exacting compositions.* The use of narrow lenses for the non-linear moments, as well as the clarity of editing in the film's climax, making comprehensible some truly mind-blowing conceptual material, is impressive. Jóhann Jóhannsson's tonal score buoys the emotions without telegraphing them. *Read here for my thoughts and breakdown on use of visuals in Villeneuve's previous film, Sicario. Image courtesy Amazon Studios.

6. Manchester by the Sea "I can't beat it. I can't beat it. I'm sorry." Directed by Kenneth Lonergan. With Casey Affleck, Michelle Williams. Winner Best Actor, Screenplay (Oscars). Synopsis: A man attempts to keep life going while besieged by family losses both past and present. Theatrical Trailer. It makes sense that Lonergan and Martin Scorsese are friends. Both directors make films about people who don't change. Think for a second how rare that is in movies… and how common it is in life. Do people, at their core, ever actually change? Only from the fifties onwards did "character arcs" become prevalent in film. Now we think they're normal, even necessary. The works of these two are refreshing in many ways, but fundamentally in a manner we often can't quite nail down; this is what that elusive spark is, that feels so much more lifelike. Henry Hill and Jordan Belfort haven't learned anything by the end of their respective narratives (Goodfellas and Wolf of Wall Street*)… but we have, watching them. In a way it's more powerful this way. To explain (SPOILERS): I think the great tragedy is that throughout Manchester, every single character who's close to Affleck gets to a point where they can forgive him– everyone, that is, except himself. For me this sends a message about the need to forgive ourselves which is stronger than if he actually did forgive himself within the film. The audience completes the film by adding its missing component in our real lives– the underlined thought that we must forgive ourselves at some point, or else life is just too heavy, as it is for him. It's a risky move as a filmmaker, but who knows, it could motivate someone in the audience to change how they think in a more powerful way than if the film provided the solution for them. Here they have to come up with it by noticing its absence. That's what's uplifting– the takeaway. *My thoughts on Wolf, which similarly takes the tack of exposing an idea through its absence to breaking point– and then, rather than the comfortable comeuppance of other rise-and-fall pictures, indemnifies in its final shot an entity we're definitely not expecting. It's less a comedy than a lament. --- Click here for the final five!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed