|

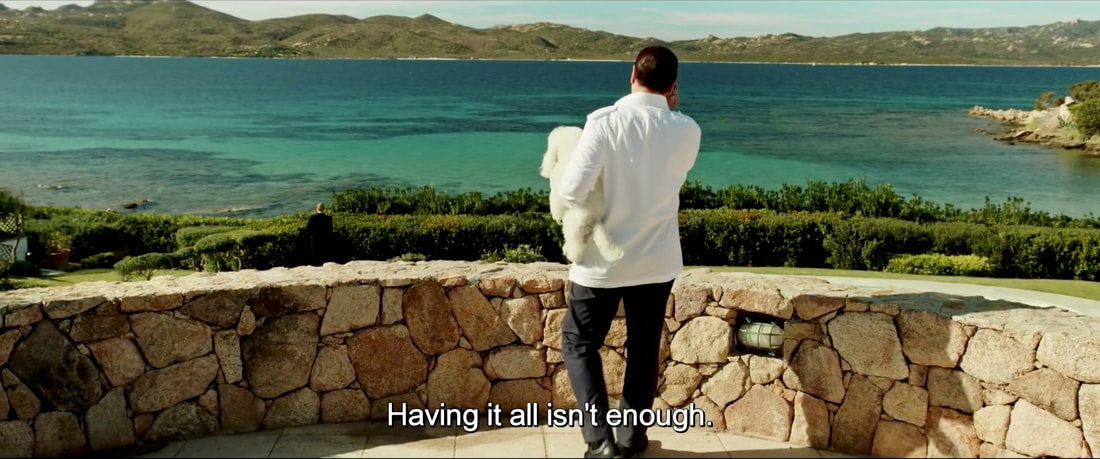

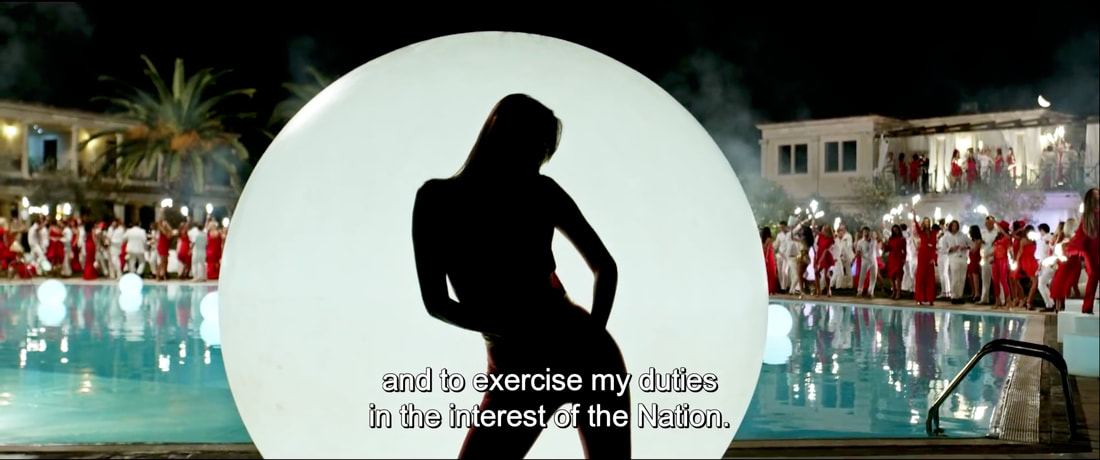

"I am a man. I am the angel of the night. I know the script of life." Synopsis: Life as lived by Silvio Berlusconi and the people who wish to gain entrance to his inner circle. UK Teaser. US Trailer. dir. Paolo Sorrentino. 158m (int'l cut)/204m (Ital. cut). 2.39:1. There are multiple ways of saying the same thing, as you know. One is to simply say what you mean. Another is to say the opposite, and then take it to an extreme, such that your viewer has no choice but to agree with your intended point. That’s satire in a nutshell, and the level of satire on display in Paolo Sorrentino’s latest, Loro, borders on the sickening. But it’s all the more effective for doing so. The “Trump of Italy,” for those who don’t know Silvio Berlusconi, was the most powerful man in Italian politics and culture for a period of decades, legendary for his wild parties and laundry list of corruption, up to and including the list currently detailed on Wikipedia: abuse of office, defamation, extortion, child sexual abuse, perjury, mafia collusion, false accounting, embezzlement, money laundering, tax fraud, witness tampering, corruption and bribery of police officers, judges and politicians. Sorrentino is in a unique position. What more is there to say about Berlusconi, after the heavily documented travails above? No, the systematic breakdown of wrongs does not interest him; others have done that well. Nor even does a humanizing approach, exploring what made Silvio become Silvio, a la liberal director Oliver Stone’s downright sympathetic take on Richard Nixon. No, Sorrentino’s interest is in us, and how we look at such self-serving and rampant liberties– with repulsion, and yes, also with attraction. His concern is with the act of looking. The gaze. We are drawn in by our repulsion. We love being repulsed, because we can then judge, as we live out our id’s worst impulses, usually at the expense of others in life, and of ourselves on screen. How Sorrentino achieves this is quite a different approach then any number of other rise-and-fall narratives. The first half of the film doesn’t even feature Berlusconi, but rather the people who want to be Berlusconi, who want to get close to him. That attitude is the subject of the film: the title translates to Them. It’s not about Berlusconi persay. It’s about the impulse to become one of them, the In Crowd, free from both guilt and rules at the expense of others. It’s among the more important films on these lists, because that is the focal point of the new apathetic nationalism sweeping the globe. It says what it needs to say by saying its opposite, guiding us through a seething, vacant cesspool of humanity such that by the time we get to that closing shot of the construction workers, we have a new basis for what we find repulsive and what we’re drawn to. We’ve been partied out, and nothing looks so good as the truthful exhaustion of a team of guys on a work break. There’s a corollary here to Scorsese’s Wolf of Wall Street, except that ended with a condemnation of the American public’s impulse toward greed; this one has a different focus, concluding with a redefining of what’s compelling. I read it as slightly more hopeful. Sorrentino expects the viewer to pay attention on multiple levels– the sensual, the moral, ethical, sociocultural and of course, the political. How does he manage to make those parties feel so unsettling? It’s all the more remarkable because he doesn’t detract from their sensual dynamism; he revels in it. I defy a viewer to name a film with a more formally sophisticated and visual aesthetic than what’s on display here. Look at those images in the trailer. As with The Great Beauty and Youth, Sorrentino continues his streak of unbridled visual feasts of color and shadow, expanding his flair for contrasting the old and the new, the sacred and the profane, light and dark. There isn’t a single frame that doesn’t glow with precision and radiant photographic excellence. The formal daring here, the oblique method of address to the viewer, and offer of periodic clarity amongst the endless sordidness make for a bleakly hopeful and entirely engaging experience. Like the Rob Reiner character in Wolf, Sorrentino tips the hat of his personal opinion only once: in the form of Alice Pagani’s Stella, a dancer who stands in for every silent but thoughtful figure on the periphery, but whose voice we get to hear. She has eyes for things beyond what Silvio considers the ultimate, and can perceive– easily– what he can’t begin to. Silvio’s insecurities keep his conversation with her on his mind for years, but even a decade later he has to defend himself to himself, instead of listening to the truth she’d once shared. But what else are we to expect? Who’d be able to hear a voice beside their own after a life lived like this, and for that long? Good thing we only need to watch this movie, rather than live it. A difficult work like this benefits from context from its maker. Far more relevant than anything I can contribute are these, a few words from Mr. Sorrentino:

On whether we should find Berlusconi sympathetic To the LA Times, actor Toni Servillo says: "No, I certainly don’t want people to feel sympathy for him. I would like audiences to observe this film with a critical slant to reflect about what happens when people who have nothing to do with politics get into politics. And that degenerates the nature of the political spectrum. It creates a system of stalemate. I would like people to be aware of the fact that there are very few scenes in the film that take place in the political chambers because you have people who trained and shaped their approach to life outside of the political arena. And when that happens, they end up protecting the interests of the few and not the interests of the people." Sorrentino adds: "No, I didn’t want to humanize Berlusconi. I concentrated on the man and not the politician. To latch onto what Toni was saying before, Berlusconi as a politician did not produce any extraordinary results. Berlusconi’s political life is known to everybody. What is more mysterious is the human aspect. And that is what I found more interesting for the film. I just wanted to tell his story the way I understood it, that at the bottom of his behavior there is a great deal of fear, fear of aging, a fear of getting old. And there’s a complex relationship that the ultra-rich have with themselves. They are frustrated by the fact that their wealth does not ensure them something more than what everybody else has." On female bodies Variety asks, "There are a lot of naked female bodies in the film, which of course reflects the bunga bunga period. But some Italian critics have said you harped on the titillating aspect a bit much, in a way that could be perceived as exploitation. What’s your response?" Sorrentino: "I don’t agree. It’s the representation of a certain specific period 10 years ago, a world that had a rather limited intellectual component and relied on bodies as a communication tool. That’s a fact that I didn’t make up. I just put it on screen." To GQ, on recreating the parties: "All I did was stick to what the press relayed. I didn't go beyond that because I would have been just making guesses which is not what I wanted to do. I really strictly followed what was all over any newspaper. In terms of the style and mise-en-scène, my focus was... There is a side of mankind that is deeply attracted by vulgar things. There is a certain sensuous nature to vulgarity. So this was the issue." On depiction vs endorsement Vulture asks, "Whenever someone makes a film about men who live extravagant lives of sin — we saw this with The Wolf of Wall Street not too long ago — detractors will accuse them of indulging in the same extravagance they’re condemning in the film. How do you respond to such charges?" Sorrentino: "This is an old controversy that has gone on forever, with regards to violent films. 'If you make a violent film, you must be glorifying violence,' and so on. Any person, regardless of how abject or deplorable they can be, is potentially worth being put on screen. Because putting something on the screen allows you to understand what can otherwise seem distant or incomprehensible. "The objective is not to glorify, at least not for me, nor is it to point a finger and decide which men are good and which men are bad. That’s the wrong approach for art in general, whether it’s a film or novel. This film gives us an opportunity to get an in-depth understanding of all sides of this man, and that’s why it had to be two and a half hours long. Reaching that understanding means exposing certain bothersome facts. If aspects of this film bother and audience, that is a crucial step on the way to understanding. "For example, this film is about a triumph of vulgarity. I don’t think it should be my job to say, 'Look how ugly vulgarity is, and how ugly these vulgar people are.' That would be an excessively Manichean way of looking at the world. This ambiguity can be unpleasant and uncomfortable, and doing it this way gets fewer positive responses from viewers, but it’s necessary to show the beauty of vulgarity. It is beautiful. Why else would it be so popular? I am more interested in interrogating what is so attractive about a life we can also find repulsive." On older male protagonists GQ asks, "Another common thread in a few of your last films is that the main characters are these aging men who they're struggling with their loss of relevance. What is it about that kind of psyche that you want to unpack?" Sorrentino: "I don't ask myself a lot of questions [about] the choices I make and the reasons behind them. But having said that, what you just stated is undoubtedly very true. I do like to talk about these characters who are caught at the moment of their decline and they tend to turn towards a melancholic attitude. They are afraid of death and they inevitably make wrong decisions and it's something that does happen when in aging they try to have one last stroke of vitality and this can become pathetic and ridiculous. "These kind of mood and feelings are very much in tune with how I feel and I like talking about them. It is true that I've focused on male characters and older male characters….I will no longer make movies about that kind of man. I did two on two politicians and then I did the pope series. So I believe that the chapter of my life about that kind of subject is over… Now I want to focus more on women and on young people. Maybe when I was young myself, I was interested in older people. Now that, unfortunately, I'm turning toward that other stage of life, well I'm going to flip my attitude and look back at you now." To Time Out: "For me, it was about capturing a time in life where you are attempting to grab back at youth, even if your body is going in the other direction." He adds to Variety: "[Berlusconi] always had this narrative about himself as someone driven by uncommon pride, by an iron will, by an indestructible determination. We’ve never understood whether behind this there were some pockets of pain, of failure, of melancholy." On two films vs one film Vulture asks, "Loro was released as two films for Italian markets. Could you talk us through the process of condensing them into one?" Sorrentino: "The first part of the film was where I did most of the cutting for the international version, because it mostly dealt with the courtiers surrounding Berlusconi. The story delves more into these ancillary characters, who are more recognizable to people reading the Italian news and keeping up with the country’s current events. The average foreigner probably isn’t aware of all this minutiae, so I cut that from Part One, and it didn’t compromise what I’m trying to say with this abbreviated version in the least." --- Nathan's Films of 2019 Index here.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed