|

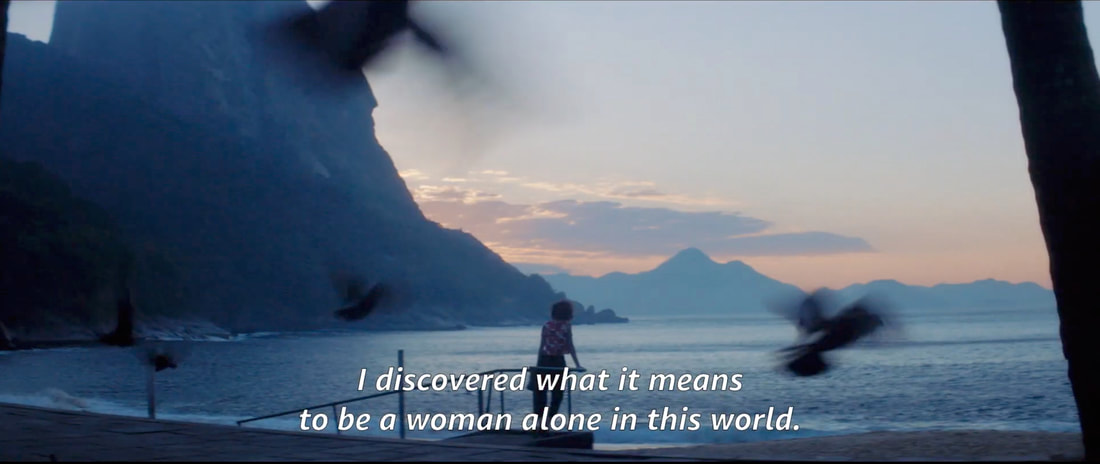

1. 1917 "I hoped today would be a good day." Synopsis: Two soldiers are assigned the task of hand-delivering a message to prevent a deadly attack. Trailer. dir. Sam Mendes. 119m; 2.39:1. Here’s the thing about unbroken takes. They’re incredibly difficult to create. The only thing harder to do in cinema, requiring more planning and careful execution than an unbroken take is… a longer unbroken take. Mendes’ 1917, like Birdman (teaser), is composed of a few unbroken takes, stitched together at key moments (usually a frame of pure black, a la going in and out of the tunnels) to appear like a seamless move. Mostly, however, scenes run for dozens of minutes at a time where there is absolutely no opportunity to break. The fact that the film is comprised of a few unbroken takes rather than a single massive one does not detract from the enormity of its accomplishment. Because you still don’t want to screw up a 30-minute take. Even a 3-minute shot is a massive accomplishment, and something to be proud of; look at the legendary opener to Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil. Who can forget that camera gliding over the tops of the buildings and coming all the way back down? Mendes and superstar DP Roger Deakins have etched into the medium’s legacy something that will stand as a pinnacle for a long, long time. A move like this is simply too difficult, too complex, and in need of too much skill for people to try and replicate. Popular films start trends; this one won't. It’s just too hard to do. Look at the scale of this thing. An airplane crash, a fire, crowds, explosions, stunts, with every moment blocked and rehearsed, every aperture change and focus pull, the camera switching mounts as it glides over rivers and out windows, into basements and over rubble. Birdman had the advantage of a controlled indoor environment. This is something else entirely. The unbroken take forces us to confront the reality of what we see, to realize we’re experiencing time exactly as the actors are. We really are going to walk across to that horizon with these two actors, and we’re going to do so them in real time. Mark Strong and the troops really are waiting on the other side of the hill for this whole section, because we come upon them in the same shot. It’s the breathtaking magic of truth. The immersiveness, the jaw-dropping you-are-thereness, of being able to truly believe what you are seeing on so many more levels than normal… this is one of a kind, and though it isn’t the best picture of the year, it is entirely and absolutely worthy of winning Best Picture of the year this Sunday, as it probably will. A milestone. Further thoughts on Birdman and unbroken takes here. 2. Parasite "Min-hyuk, this is so metaphorical." Synopsis: An unemployed family infiltrates a wealthy one, and things get complicated. Trailer. dir. Bong Joon-ho. 132m; 2.39:1. So much ink has been capably spilled in the exploration of this film's many themes and able execution. I'll be brief. Lee Chang-dong's 2018 masterpiece Burning may have tackled similar issues and more with greater nuance, restraint and mystery (look for an essay by me soon), but we can’t fault Bong for that. There’s room for more than one film on class differences in Korea, and this one is thoroughly deserving of its legendary accolades. Parasite is more commercially digestible, and if it gets viewers on board with arthouse and international films, all the better. His direction is precise, with razor sharp editing, deftly executed delineation and reveals of information, and highly controlled camerwork with distinctive movement choices for each class level. Like so many of the pictures I'm reviewing this year, it's a touch violent for me, but spectacularly well made. 3. A vida invisível de Eurídice Gusmão (The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão) “My sister didn’t run off.” Synopsis: Two sisters live their lives after being separated by the men in their lives, each unaware the other is nearby, and struggling. Trailer. dir. Karim Aïnouz. 139m, 2.39:1. In her landmark 1971 essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” art historian Linda Nochlin reminds us that saying 'you can tell this was made by a woman’ is a fool’s exercise. She writes that “in general, women's experience and situation in society, and hence as artists, is different from men's, and certainly an art produced by a group of consciously united and purposely articulate women… might indeed be stylistically identifiable as feminist, if not feminine, art. This remains within the realm of possibility; so far, it has not occurred” (emphasis mine). She continues: "No subtle essence of femininity would seem to link the work of Artemisia Gentileschi, Mme. Vigee-Lebrun, Angelica Kauffmann, Rosa Bonheur, Berthe Morisot, Suzanne Valadon, Kaethe Kollwitz, Barbara Hepworth, Georgia O'Keeffe…” The list goes on, including Sand, Woolf, Plath, Eliot, Sontag, Dickinson and more, before concluding that “In every instance, women artists and writers would seem to be closer to other artists and writers of their own period and outlook than they are to each other. It may be asserted that women artists are more inward-looking, more delicate and nuanced in their treatment of their medium. But which of the women artists cited above is more inward-turning than Redon, more subtle and nuanced in the handling of pigment than Corot at his best? Is Fragonard more or less feminine than Mme. Vigee- Lebrun? Is it not more a question of the whole rococo style of eighteenth-century France being "feminine," if judged in terms of a two-valued scale of "masculinity" versus "femininity"? …In any case, the mere choice of a certain realm of subject matter, or the restriction to certain subjects, is not to be equated with a style, much less with some sort of quintessentially feminine style.” Nochlin invites us toward the unpopular notion of judging people not by their gender but more fundamentally by their humanity, and if they be artists, than their art by their artistry. Experience and perception transcend gender norms, and I think of Nochlin’s words whenever I think of this film, and versa vice. The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão is the year’s best argument that men might have something relevant to say about the evils of patriarchy. No innocent viewer would ever assume its director was male, given not just its sympathies but its potent, delicate, and expansive understanding of its principal topic: female oppression by men, what it feels like, and how it alters and limits the course of lives. The passion and anger quite simply bleed off the screen. Marketing materials bill it as “a tropical melodrama,” and it earns the term not so much from its story content as its tone: strong. It’s heavy stuff, and unlike many melodramas it carries the unmistakable whiff of truth. As a viewer and member of modern society I found it essential, and as a filmmaker who couldn’t be less interested in writing male main characters, I found it instructive and inspiring. More importantly, the two protagonists move me tremendously in doing what one does under hopelessly unjust circumstances: you do what you can, and make the most of things. Aïnouz’s wide frame captures image after image of earthy, sensual beauty; the (digital) picture was lit and color-timed to match 16mm daylight stock. The replication of 60’s and 70's era color film is uncanny, down to the underexposed interiors and hints of saturated color bleed outdoors. A beautiful and heartrending picture. Nathan's Films of 2019 Index here.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed