|

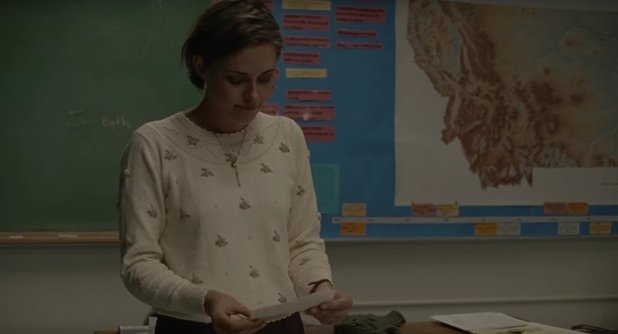

Above image courtesy 20th Century Fox. People sometimes tell me the blog needs to focus more on me. That I write too much about everyone else, and what about the recurring bus driver in ever single one of the stories? What's he like? The thing is, I'm not all that interested in writing about myself. Maybe I'm just barely too old. I grew up before the internet. I don't take selfies. I don't take pictures of everything I eat. Living life is more interesting to me than documenting it– but that's another can of worms. Navel-gazing has reached new heights in the age of social media, and in the way "nerd" and "geek" have (thankfully) lost most of their traction as hurtful labels with the advent of widespread digital technology, so too has "narcissism" started to be, if not a positive, too pervasive to be much of a put-down. But it will (thankfully) never be a completely good thing. While accusations of nerddom had more to do with unkindly accusing someone because of their interests, the label of narcissism is different. It's less about interests or even interest with oneself than a critique of lack of interest in others. The behavioral extension of that, selfishness, remains as uncelebrated in day-to-day interactions as it ever was. For myself, I write about others because I'm more intrigued by them. It's their actions which move me, not my own. I'm grateful though, when readers take an interest in the posts which do focus more on me (such as the recent "Nathan Takes a Day Off" series), and I completely understand the need for character development. Who is this guy, after all, who shows up in every post, and what's he like? We don't care about characters in films or books unless we know something about them, and this desire makes sense to me. I learn about people most enjoyably when listening to them talk about things they love. Hopefully my thoughts on why these films resonate with me offers the same, and more importantly, functions as a list of recommendations for those nights when you're trolling Netflix, unsure of where to click next! --- This is supposed to be a list of overlooked 2016 films. I realize we're well into 2017, but I had to wait to see a few key films before I compile in good conscience. Also, there's a drawback to throwing together a top ten right at the end of Oscar season, as everyone does; you're too prone to overrate whatever films you most recently saw. There's a review of mine online somewhere (which we're definitely not going to link to!), where I gave way too many stars to a certain Ashton Kutcher-Kevin Costner water rescue flop… I think mostly because in those days I had to submit reviews within 24 hours, and my natural enjoyment of the act of film-watching just gets in the way. So. This is a list where I've let things stew a while, and hopefully that makes it more useful as a resource for you. Personally, I think 2016 was a banner year. It wasn't quite up there with the cornucopias we got in 1999, 1969 or 1939 (why is it always the -9's?), but it was bountiful. I'm calling it an "overlooked" list because I want to focus on some of the stuff that might slip through the cracks, as well as the obviously great stuff. I'll start the actual list in the next post; for an appetizer, here are four films which I'll stop short of calling great, but which moved me for different reasons. Image courtesy Lionsgate. Deepwater Horizon “Hope ain’t a tactic.” Synopsis: A dramatization of the 2010 oil rig explosion. Theatrical trailer. I know. You didn't think this was going to be here. I'll start talking about obscure Brazilian movies in a second, but first let's appreciate this entirely worthwhile Mark Wahlberg action vehicle. I like films which explore the potential for truth-telling in realms about which I know little, and offshore drilling is a realm in which I have minimal (read: zilch) real-world experience. Peter Berg's film (he and Wahlberg have struck up a working relationship of sorts, and including this have made three pictures about real-life unsung working class heroes) spends an unreasonable time on the details of how oil rigs actually work. Berg focuses on things like how fuel injector hoses attach to a vessel, or step-by-step breakdowns of evaluating the integrity of cement work in a wellbore. Characters talk using jargon they don't explain, because every one of them would already know what the other is talking about, and we lean forward to piece it all together. The texture of life on a rig and how those enormous machines work, as well as a glimpse into the lives of the salt-of-the-earth folk who work them, hugely compels me. It's comparable to my fascination with the first act of United 93 (trailer), before anything goes wrong, where we're given unapologetically detailed views into the complexities of air-traffic control. I would have been fine with either of these films being about nothing more than that, rather than the disasters they eventually both end up focusing on. Isn't it all so interesting, what life looks like in all its many iterations? Image courtesy IFC Films Certain Women "It'd be so lovely to think that if I were a man, I could explain the law and people would listen and say okay. That would be so restful." Synopsis: Four women– a teacher, lawyer, wife and ranch hand– strive to follow their own paths in the American northwest. Theatrical trailer. In his 2003 book Mortals, Norman Rush writes about how most every society through history has subjugated about half its population. Men never have to wonder what it'd be like to follow a list of rules the other gender came up with; women have to do that all the time. To find peace being forever relegated to a supporting role– in society, in relevance, in perceived ability– has for too long been a sadly necessary feat of accomplishment, and one which goes unsung daily. Kelly Reichardt's wonderful new 16mm picture is an exploration into three such unsung lives. What is the wife thinking, when her husband steps in during a land purchase, on the unspoken assumption she's incompetent at explaining herself? What's it like to be an underpaid teacher given a job in the middle of nowhere? The film isn't angry, but calm; not polemic, but observant. It's a window into the minds of what would normally be underdeveloped supporting characters, and a reminder of the complexity of lives outside the spotlight. Worth noting are all the performances (especially Michelle Williams), but I have to single out Kristen Stewart. You may know she was the first American actor in history to win a César (the French equivalent of an Oscar) for her performance in Olivier Assayas' Clouds of Sils Maria, and I say she deserved it. Nick Davis in Film Comment writes: "[H]er commitment to a low-fuss, conversational directness is rare among modern film performers, particularly in roles that accommodate flashier approaches…. She has persuaded the film community to meet her where she lives– in a laconic, minutely expressive, barely laminated register of acting that's confusable with 'just being.' …The sheer ordinariness of [her] gestures [Davis notes: "a redoubtable poker face, hunching, biting or curling her lip, rolling her eyes amid unvoiced thoughts, looking down, looking far away while cupping her head of her hair"], collapsing any border between acting and behavior, suggests something familiar, something ubiquitous: less the icon of an agitated generation than one of its many median exemplars, the needle but also the haystack. While seeming to 'do' little onscreen, Stewart paradoxically renders transparency and impenetrability, rarity as well as its opposite." I see Stewart in the position Leo DiCaprio was in the years following Titanic; a talented actor struggling to improve his craft, be taken seriously, and climb out from under the shadow of a blockbuster which threatened to define him without requiring his skills. Her performance here is hugely exciting in its subtleties, and her collaborations with Assayas, in the aforementioned Clouds (trailer) and this year's Personal Shopper (trailer) are, without exaggeration, acting masterclasses. Image courtesy The Orchard

Demolition & Louder Than Bombs "Repairing the human heart is like repairing an automobile. You have to take everything apart, examine everything, then you can put it all back together." Synopses. Demolition (trailer): An investment banker (Jake Gyllenhaal), following the death of his wife, finds solace in demolishing his former life. Bombs (trailer): A family has differing perspectives on the death of their mother/wife (Isabelle Huppert). Nobody liked these movies. Except me. Panned by critics and ignored by audiences worldwide, I nevertheless gobbled them up, and I imagine a few other solitary souls out there did too. I've been thinking a lot about grief, and grief is the subject of these two pictures. Demolition, by the Québécois Jean Marc Vallée (Wild, Dallas Buyers Club), follows Jake Gyllenhaal after his wife dies in a freak car accident; Joachim Trier's English-language debut, Louder Than Bombs, follows the family of a war photographer (Isabelle Huppert) after she dies in her own car accident. Demolition is about the problem of numbness in modern life, and how it relates to grief. How do you miss someone you never knew? How do you touch emotions, break through the fog of a society which disencourages truthful, raw, honest communication? Louder Than Bombs revolves around the impossibility of belonging in a family when you're away for long periods. When you miss years of the in-between moments, washing dishes and loading the car, you end up becoming a stranger. You find that those were the meat of it all. You try to learn what your children are interested in, what their concerns are, but the next time you're back that's ancient history, and you've got to relearn it all over. It doesn't often get mentioned in our culture that after a certain age, people you love will start dying. Their health will decline, and with enough time it won't get better, but gradually (or suddenly) worse until it's over. Nobody gets out of this game alive. What to do? You know the answer. You always knew. Live in the present. You can't be happy otherwise. It's what kids know how to do so well, a skill we don't have to forget. I went to an Emily Wells concert in 2012. She told us then, "we're going to lose everything we love in this life." I've spent the last five years thinking about that line. I saw her again a few weeks ago. This time she said, "everything I've lost, I've learned to quit." A different mental hurdle, but equally important. The 2012 line was about preparing for something; the 2017 line is about dealing with the aftermath. The best and worst of us will all address these two issues, imperfectly, but that's okay. We do what we can.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Nathan

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed